The Quartz Mill AKA Chilean Mill is one of the more popular types of the original Chilean mill. Still used for certain grinding problems, this mill employs the convex-concave principle of crushing ores, resulting in a product surprisingly low in slime content and which has its particles, such as sulfides and gold, well polished and free of recovery retarding tarnish.

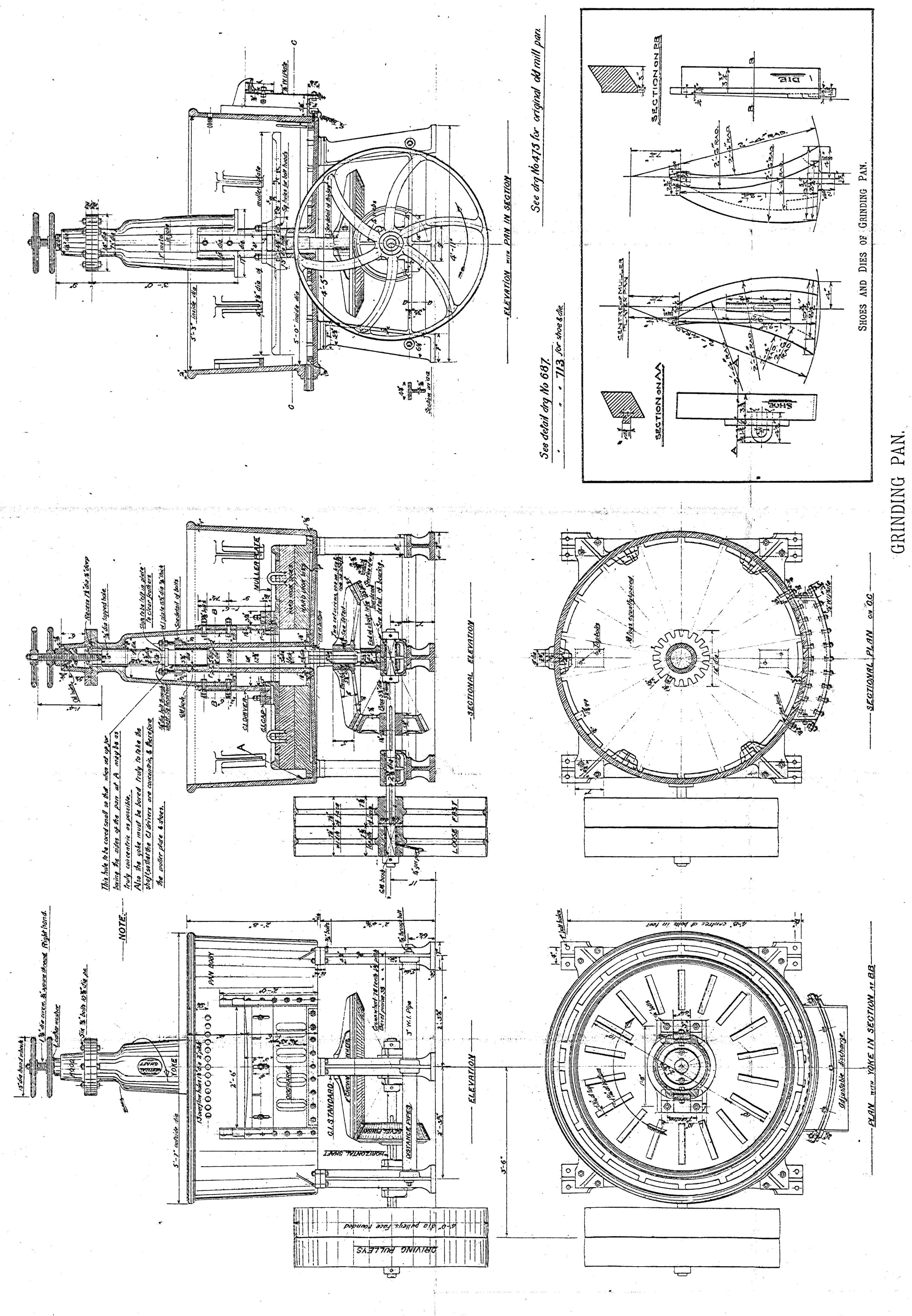

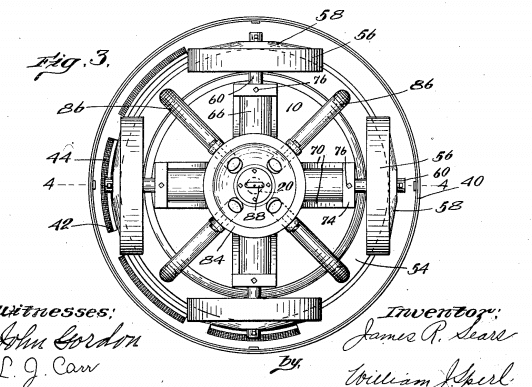

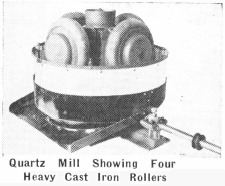

The Chilean Mill consists essentially of four heavy cast iron rollers with convex surfaces which are rotated on a concave surfaced die ring. The purpose of this design is to keep the ore between the crushing surfaces at all times, thus avoiding the necessity of scrapers to direct the ore into the crushing areas, and also to avoid spillage. Operation has shown very low maintenance costs possible due to longer life of wearing parts and to mechanical simplicity of operation. Also see the Arrastra.

Although modern ore dressing practice employs Steel Head Ball-Rod and Ball Mills in preference to the Chilean type mill for grinding purposes, there is a field for these units where coarse grinding is required.

Chilean Mill Capacity

The Chilean Mill was used in gold mining in small gold amalgamation plants.

Mercury was introduced into Mexico as a means of extracting the precious metals by Bartolome Medina in the year 1557, and its use doubtless soon spread to Peru and the neighbouring countries. When Barba wrote in 1639 there were three amalgamation machines in use in Peru, the mortar (used in the Tintin process), the trapiche or Chilian mill, and the maray. The mortar was hollowed out in a hard stone, the cavity being about 9 inches both in diameter and in depth. The ore was triturated with water and mercury in this mortar with the aid of an iron pestle, while a stream of water, flowing through, carried away the crushed particles. The slimes were roughly concentrated, but most of the gold remained in the mortar with the mercury.

The maray, although equally primitive, was probably of greater capacity: it makes use of the principle employed in the bucking hammer. About the year 1825 Miers saw it in Chili, where it is probably still in use. It consists of a flat or slightly concave stone, 3 feet in diameter, on which lies a spherical boulder of granite about 2 feet in diameter. This is rolled to and fro by two men seated on the ends of a long, wooden pole, which is firmly fixed to the boulder. Ore, water, and mercury are ground together in this machine, and then washed down.

The Chilian mill closely resembles the edge-runner mill of the present day, which is used for grinding and mixing mortar. The Peruvian trapiche had a similar circular bed of hard stone, but only one stone runner, which was driven by mules. The Chilian mill is still used to prepare ores for treatment in the arrastra, which was not mentioned by Barba, and may perhaps be regarded as an outcome of the trapiche.