Repeated failures in attempts to work gold-bearing gravels by means of suction-dredges have created the impression that this method is impracticable. The suction-dredges have failed from three special causes: excessive wear and frequent breakage of pump-shell, runners and liners; inability to dredge compact gravel which would not readily move towards the intake; and, most important of all, closing of the suction-pipe by stones too large to enter it.

In my opinion, all three causes of trouble may be remedied: the first, by making stronger the parts most liable to wear and breakage; the second, by means for loosening the gravel at the intake; and the third, by sufficiently increasing the diameter of the suction-pipe. In suction gold-dredges, this diameter has not usually exceeded 10 or 12 in.; whereas there are few profitable gold-fields which can be considered dredgeable, in which stones more than 12 in. in diameter are not frequently encountered.

II. An Effective Suction-Dredge:

In harbor-operations, much larger stones are handled by suction-dredges. The large dredge of the Henry Steers Contracting Co. worked for nearly four years at League Island, Philadelphia, where it sucked up, passed through the pump, and forced through 3,700 ft. of discharge-pipe, gravel containing boulders up to 200 lb. in weight. This was done with no bad breaks and few shut-downs. The cutter and liners were the only parts liable to damage, and these were easily replaced with brief interruption of work. The chrome- steel liners are said to have lasted from six to nine months. I am informed that this dredge worked continously for nine months at Harrison, H. J., on gravel, much of which carried stones as large as a man’s head.

The essential features of this dredge are as follows:

The centrifugal pump, made by the Morris Machine Co., Baldwinsville, N. Y., was designed for a 22-in. suction, discharges at the bottom, and is driven at 225 rev. per min. Its shell is approximately 84 in. in diameter, with a runner about 60 in. in diameter. The runner-bearing has a water-sleeve to keep the sand out, supplied by a small force-pump worked at 60-lb. pressure. The pump is set 30 ft. from the bow. Power is supplied by a compound marine engine, with surface-condenser, 22 by 42 in. by 26-in. stroke, running 90 rev. per min. On the engine shaft is a 65-in. gear with wooden cogs, driving a 26-in. steel pinion. The wooden cogs are said to run about six months before renewal. On the pump- shaft keyed into the pinion is a slipping spring coupling. When a stone or log, too large to go through, gets into the shell, the runner is brought to a full stop without damage. This occasionally happens, and the obstacle may be removed by taking off the plate, with a loss of time averaging not more than 15 min. The pump uses from 450 to 500 h.p., which is considerably in excess of the economical requirement of a pump of this size, but with it the material may be forced through a pipe line 4,000 ft. long. I am told that, with 1,000 ft. of discharge-pipe, 1,000 cu. yd. of gravel per hour may easily be handled. The total power used on the dredge is 800 horse-power.

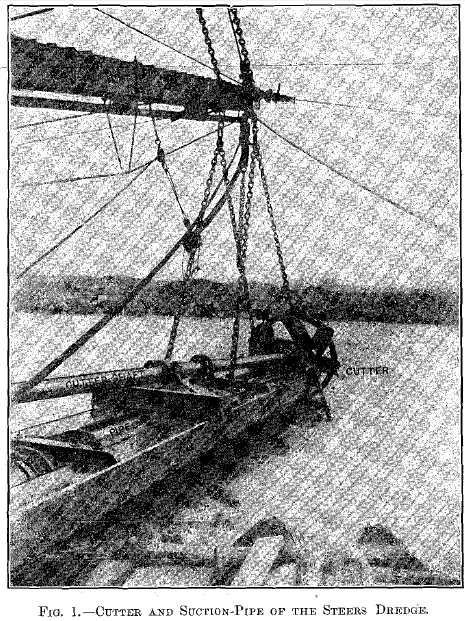

The winch, with its various barrels for working-lines, suction- and cutter-hoisting lines and spud-hoisting lines, is a Lidgerwood machine, with two cylinders 14 by 18 in. The winch-engine also drives a chrome-steel gear, which through a shaft drives a 7-ft. chrome-steel cutter. In Fig. 1 a 6-ft. man is shown standing in the cutter. The cutter-shaft is connected with and driven by a universal joint. The wrought-iron suction-pipe, the mouth of which is just above the lower rim of the cutter, is connected by a flexible rubber joint to the cast-iron pipe which extends to the pump. The two timbers used as braces for the shaft and pipe are so hinged that their movement can only be vertical. The wrought-iron suction- pipe lasts for a year; the cast-iron pipe, including the elbow running from the rubber joint to the pump, lasts four years. The rubber elbow lasts from three months to a year.

This is said to be the largest suction-dredge in the world that has continously handled coarse gravel, and in capacity is the largest gravel-dredge of any class. The outboard suction is 54 ft. long, and the dredge can work to a depth of 30 ft. I am told that it has frequently sucked up from the bottom heavy spikes and tools which had been dropped into the water several feet in advance of the pipe.

The dredge is controlled by one man, standing behind a row of levers connected with the suction-hoist, various valves, etc. A vacuum-gauge shows the amount of material coming through the suction-pipe; a pressure-gauge shows whether the material is passing freely through the discharge-pipe; and a skilled operator finds little difficulty in maintaining a fairly uniform movement, and as constant a ratio of gravel to water as can be secured with a bucket-dredge.

It seems safe to assume that, for the excavation and transportation of gold-bearing gravel, even containing large stones, this apparatus, provided with a cutter, to loosen such gravel as will not break up in the suction-pipe current, a centrifugal pump capable of producing a sufficient current, and a pipe large enough to pass all ordinary boulders, could be successfully employed.

In the original Bucyrus gold-dredge, the second lift was made by a centrifugal pump; and the same means, I believe, has been employed in dredging the phosphate-deposits of Florida.

III. Special Conditions of Gold-Dredging:

To adapt this design to gold-dredging, suitable means for the saving of gold must be provided. Where the metal is in heavy, shot-like particles, as at Bannock, Mont., its specific gravity will carry it quickly to the bottom of a sluice with deep water, carrying fairly coarse gravel; but where it is scaly and fine, like that found in the gravels of Oroville, Cal., in the Choco region of Colombia, and in most other gold-dredging fields, a current of water strong enough to move the gravel will carry with it practically all the gold. This was clearly shown at Oroville on the Continental dredge, where, as I am informed, until an elaborate system of undercurrents was introduced, not enough gold was saved in the sluices to pay for the trouble of cleaning up. In the Choco, operation of the dredges Margaret and W. T. Curtis proved that, with currents in the sluices strong enough to carry the gravel, virtually no gold was held in the riffles. The old hydraulic-mining sluices, in which grizzlies and undercurrents played such an important part, and the early pick-and-shovel telescope-boxes, used even now in some fields, show that, in order to save gold directly, the current must be below that required to move coarse gravel, since otherwise the gold will go with the gravel to the tail- race.

Indeed, the pay-streaks of gold-bearing placers and gulches, considered as natural sluices, tell the same story; for the gold which they contain has been transported by water, sometimes to long distances from its source in the rocks, and deposited only when the current has been checked or slackened. On the other hand, when some such change causes deposition, that process (if not interrupted by extraordinary events like heavy floods) may go on for a long time at the spot thus designated by nature. In testing with the pan hundreds of pay-streaks, from 3 to 4 ft. or even more in thickness, carrying fine gold, I have found that, except for a few inches on top, they were generally of equal value to the bottom.

IV. History of Suction-Dredging in Gold-Bearing Gravel:

In this connection, it is unnecessary to repeat, or even to summarize, the data relative to the carrying-power of water, which are available in other forms. This phase of the subject has been covered in my paper on A Sea-Level Canal at Panama, presented at the present meeting of the Institute. Much of the information therein presented has a direct bearing upon the problem of handling gold-bearing gravel by currents of high velocity. Theoretical conclusions on this point have been confirmed by experience also.

The following data, accompanied with references to the authorities cited, may serve to show the experience heretofore had with suction-dredges in gold-bearing gravels, and to guide the reader in more detailed inquiry:

At Alexandra, New Zealand, in 1887, a Welman suction- dredge was put in operation, and others were built later along the West Coast ocean beaches. They were found capable of dealing with fine gravel, sand, and shingle, but were not adapted to coarse gravel and large stones. For this reason they did not come into permanent use.

In the neighborhood of Waipapa, Otago, New Zealand, suction-dredges have been found suitable for handling sand and small stones. Concerning this type, T. A. Rickard wrote in an able paper on Alluvial Mining in Otago:

“ For irregular bottoms, the suction-pump dredge, of which the Welman is a good example, will be found best adapted. In this case, a powerful centrifugal pump draws up the water, gravel and gold, delivering them to the level of the tables. At Waipapa, stones 35 to 40 pounds in weight have been sent up by the pump ; and it only requires an improvement in construction, giving durability and strength, to render it a most effective machine for this class of work.”

At Six-mile Beach, on the ocean beach, about 18 miles from Fortrose, towards Waikawa, New Zealand, a dredging- plant was in operation (1890), consisting of a boat carrying a Welman dredge, and a centrifugal suction-pump, 3 ft. 6 in. in diameter, with a 13-in. delivery-pipe, and a velocity of 260 rev. per min. The swinging suction-pipe had a radius of 40 ft. and was fitted with a sleeve-nozzle and revolving cutter. The gold-saving tables were 64 ft. (?) wide, and had a fall of 1.5 in. per ft. Side-boxes collected the tailings and carried them to the stern of the dredge, where they were discharged through a 15-in. pipe, with a universal-socket joint, suspended from a post-crane. The material handled was mostly sand. Stones were caught on a hopper-plate and thrown, on either side, upon ground already dredged. The sand passed through the perforated plate into the hopper, and was carried by the water to the tables, upon which it was equably distributed. The gold, which is extremely fine, was caught in plush mats. The results were reported to be satisfactory.

At Lake Brunton, Otago, there was a dredging-plant (1890) generally similar to the one at Six-mile Beach last described, but with a pump capable of maintaining a current which will easily carry and pass stones up to 56 lb. in weight. Large stones caught by the arms of the runner were broken up without injury to the centrifugal pump. Still another dredging- plant of this type, on Waipori Flat, proved successful in wet ground with no fall for draining or hydraulic sluicing.

According to Thomas Egleston, in his paper entitled The Treatment of Fine Gold in the Sands of Snake River, Idaho, much of the gold in the gravel of Snake river had for years been recovered by the simple method of gravity-concentration on burlap tables after the fine material had been separated from the coarse gravel by passing through a screen-floored sluice-box. In 1904, Robert H. Bell, State Inspector of Mines, expressed the conclusion that the suction-dredge would solve the problem of profitably working on a large scale the broad, flat bars of Snake river. Mr. Bell says the saving of the gold presents no further difficulty, but what is needed is a method of handling large quantities of the low-grade material. His opinion is based in part upon the experience of the Sweetser- Burroughs Mining Co., which, in 1894, introduced a floating suction-dredge on Snake river. It was started with a 6-in. intake-nozzle, afterwards increased to 10 in. The pump was designed to pass any stone which might reach it through the suction-pipe; and the plant had been in successful operation, with successive improvements in strength and stability, ever since its first installation, up to the date of Mr. Bell’s interesting and detailed account of it, in 1904. In that report he said :

“ The cost of handling gravel at this plant, including all charges, is 4 1-2 cents per cubic yard. Working in the river bed, most of the gravel being raised from below the water surface, a good deal of the material handled runs from 10 to 20 cents per cubic yard, and affords a handsome margin of profit.”

Unfortunately, Mr. Bell was obliged to report in 1906 that this company, having exhausted the most favorable ground available for its operations, skimming the best layers of gravel to the depth of about 6 ft., with an average yield of something less than 10 cents per cu. yd., and at a considerable profit, had suspended operations.

Mr. Bell’s description of the Snake river gold is worthy of special notice. He says, in his report of 1906, already cited :

“The Snake river’s fine gold is finer than any natural placer gold I know of. It is high grade and worth $19.50 per ounce, but requires fully 1,500 colors to weigh one cent in value ; yet under a powerful microscope, each color is an individual nugget showing abrasion marks. These particles are often coated, touched or spotted with a crystalline white film of some foreign substance that looks like silica under the glass, and this is what makes it necessary to polish it in a grinding pan before it will amalgamate freely. ”

If such gold as that can be recovered to the extent of 95 per cent., as given by Mr. Bell, from the material delivered, we may well accept his conclusion, that the real remaining economical problem is the cheap handling of the material.

On the Sacramento river, California, the operations of the Huron Submarine Mining & Construction Co. with a suction- dredge are peculiarly interesting. They are carried on in “blue ground ” from 8 to 25 ft. thick, and containing many boulders. The gold is coarse and well worn; the bed-rock is igneous and very rough. The dredge is unlike any other ever built. The boat is 65 ft. long, 24 ft. wide, and draws 2 ft. A 75-h.p. engine operates a rock-pump, an air-compressor, and auxiliary machinery. In the middle of the boat is a steel shaft made in sections for extension to any required depth. These sections are boat¬shaped, measuring in horizontal cross-section 11.5 by 8 ft. The vertical length of each section is 6 ft. The sections of the shaft are set with the sharp edge up stream, to diminish the resistance offered to the current. The lower sections are cylindrical, and the lowest is provided with a water-tight door for ingress and egress of divers. This shaft is sunk through water and gravel to bed-rock. Down through it extends the 10-in. column of the rock-pump, and a 2-in. hose to carry water at 100-lb. pressure to the mouth of the pump-column. A diver in the shaft, hose in hand, works with freedom, directing gravel to the mouth of the suction-line, and cleaning the gold from the bed-rock crevices. The capacity of the pump is 1,500 cu. yd. of gravel per day, with water enough to wash it in the sluices. A diver works continuously under water 5 hr. a day. The estimated cost of dredging is 3 cents per cubic yard.

Earlier records of California experience are given in the special volume issued in 1899 by the California Miners’ Association. R. H. Postlethwaite, in an article on Dredging for Gold, sums up as follows (p. 93) the situation up to that date concerning the suction-dredge.

“The hydraulic-suction dredge has, however, in times past, had its supporters, and immense sums have been expended on it generally with very unsatisfactory results, although there are a few cases where it can be made to work with advantage. For example, in digging sand and conveying it long distances it probably has no equal; but for lifting heavy gravel and boulders, and for the picking up of gold, it has of necessity generally proved a failure, except in very rich ground.”

As to the picking-up of gold, mentioned by Mr. Postlethwaite, I think that the failure of a suction-dredge to do this must be due to bad construction, or bad management, or both. Practical experiment, confirming all standard formulas, will show that a suction-pipe, especially if provided with a hood, and drawing its water from the bottom, can clean the bed-rock of all loose gold, including ordinary nuggets not actually wedged in very hard and solid material. B. E. Morse, a member of the Institute, informs me that, in 1899, a dredge with 20-in. suction, used by the N. Y. Shipbuilding Co. in operations for reclaiming land at Camden, N. J., frequently pumped up coins (sometimes of gold), and occasionally old Revolutionary bullets and cannon-balls, as well as innumerable pieces of iron of various forms, and once an entire musket, so that the workmen were always on the look-out for “curios.”

An article in the same volume (p. 434) by Thomas J. Barbour, on The Evans Hydraulic Gravel Elevator, describes an apparatus developed in New Zealand, and used in hydraulic sluicing, as described below. This article contains valuable data of experience as to the moving of material by water through pipes.

In Australia, hydraulic sluicing with centrifugal pumps, which should not be confounded with suction-dredging of primary material, is much used in reworking the old alluvial diggings, and has been found profitable. This method has been described under the title, Hydraulic Dredging in Australia, by F. Danvers Power. While it is not directly a case of hydraulic dredging proper, it furnishes additional confirmation as to the possibility of transporting material by means of water-currents such as the centrifugal pump can produce. In the Beechworth and Castlemaine districts (especially the latter), many plants are reported as using this method of hydraulic sluicing. Work is begun by excavating and filling with water a hole 60 ft. square and 6 ft. deep, in which the barge or scow is floated. The required head of 60 to 70 lb. water-pressure is obtained from natural sources or supplied by a 12-in. centrifugal pump. The average yield of the old placer- ground (about 14 ft. deep) in the Castlemaine district has been nearly 230 oz. gold per acre. It is estimated that a yield of 125 oz. per acre would yield a profit; and it is reported that the Castlemaine Junction Sluicing Co., after 15 months’ work, returned to its stockholders the whole of the capital originally invested, with a substantial extra dividend besides. Further details of this interesting method are given by Mr. Power in the article cited above. I will note here, as pertinent to my subject, only his report that the gravel-pumps used raise and pass boulders up to about 60 lb. in weight.

V. Conclusions as to Suction-Dredging:

The facts above summarized and other information readily accessible to the student of dredging-problems warrant the following conclusions:

The problem of gold-extraction may be, and should be, separated from that of the cheap excavation and handling of the gold-bearing material. Each can be best solved by itself, after the elimination of all the conditions which properly belong only to the other. Dredging must not be made slower or dearer for fear of a loss of gold in subsequent operations; and failure of technical efficiency in gold-extraction should not be chargeable to the method of original excavation.

The separation having been made, cheap and rapid dredging on a large scale is evidently a prime requisite for the exploitation of gold-bearing gravels.

Where the quantity of auriferous gravel controlled is sufficient to warrant a large investment, the hydraulic suction-dredge will give rapid and economical results. Such conditions are found in the newer fields of California, along the rivers of Brazil, in some of the rivers and flats of Dutch Guiana, possibly in parts of Siberia, and certainly in the large streams of Colombia, especially in the Choco district.

The greatest expense of gold-dredging, as at present practiced, is the repair of the bucket-line, including the tumblers. Bulletin No. 36 (1905) of the California State Mining Bureau (Table 5), shows these repairs amounted to twice as much as all others put together, and more than one-third of the entire operating-expense. In another place, 39.3 per cent, of the time lost in stoppages by a given machine is reported to have been due to the same cause. Judging by the record of the Steers dredge, we may assert that a suction-dredge would offer in this particular a large saving of both time and money, to say nothing of first cost, which is, for such a dredge, by no means proportioned to its capacity.

As to running-expenses, I am informed that the daily cost of operating a Steers dredge, such as has been described above, will not average over $250 per day, including interest and sinking-fund, and that its capacity of 1,000 cu. yd. of gravel per hr. could safely be maintained for 15 hr. in the 24, if the gravel did not have to be spread from a pipe. In my judgment, the allowance of 9 hr. in the 24 would cover all necessary stoppages for removing snags and large stones, and for other reasons common to all dredging-operations. Assuming the gold-saving and stacking features to cost the same as in the method of piping astern and spreading, this would give a total cost of about 1.67 cents per cu. yd., with the important additional advantage of an unprecedented daily yield.

This paper proposes, not a change of practice in the sense of the adoption of a new principle of dredging gold-bearing gravel, but a change of practice, in so far as it involves the re-adoption of a well-known principle, with such improvements in apparatus as will give it fair play. Suction-dredges have made already creditable records here and there; but they have often failed to give satisfaction or to pay dividends, by reason of their imperfect construction or inadequate dimensions, or of local conditions for which they could not fairly be held responsible. In short, the suction-dredge has not had, in this field, an opportunity to show what it could do at its best; and from my own experience I think the general tendency is to persevere in experiments with various forms of bucket-dredges, which (under certain adverse conditions only too likely to occur) are bound to fail.

What I propose, with the Steers dredge as a basis, is a suction-dredge of maximum durability and efficiency. In comparison with other mining-machinery, the gold-dredge has hardly maintained its due proportion of progress. Within the memory of many still living, the stamp-mill has been developed from the primitive Cornish battery, with a daily capacity per stamp of 500 to 600 lb. of ore crushed through an 11-mesh screen (or its German prototype and companion), to the modern plant with a daily capacity per head of 4 tons crushed through 40-mesh—an increase of 36 fold in efficiency. Within the period of a generation, the capacity of river- and harbor-dredges has increased from 800 cu. yd. per day to 6,000 cu. yd. per hour—a 75-fold increase. In gold-dredging, on the other hand, the most recent 13-ft. Bucyrus apparatus has shown a capacity not more than five times that of the original New Zealand dredges of 20 years ago.

The question of profitable gold-dredging depends on the first cost, capacity and operating-expense of the plant, as against the quantity and value of the gravel to be moved.

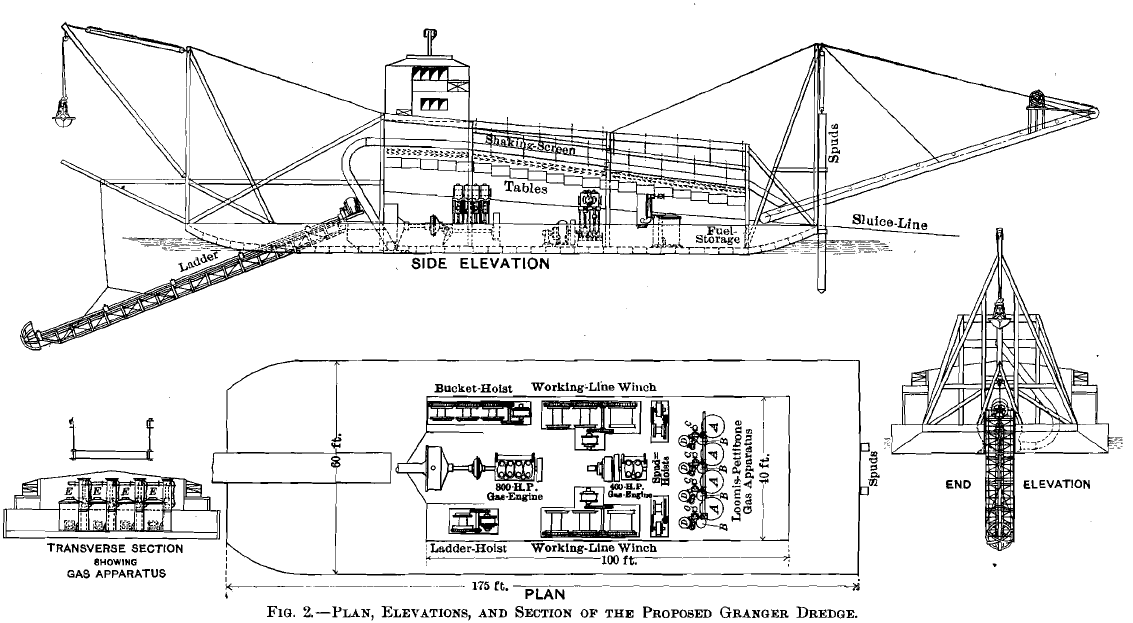

At the present time, I would regard a dredge having a capacity of 1,000 cu. yd. per hr. as a sufficient step in advance; and I offer the specifications for such a dredge. If for use in California, where commercial electricity is available, or where water under natural head can be employed, as in the latest New Zealand practice, my specifications would require modification in several items. Being under the necessity of assuming the conditions to be met, I have taken those which permit the boat to be built on tide-water at or near New York, towed to her field of work, and there operated with wood-gas.

VI. Specifications for a Hydraulic Gold-Dredge:

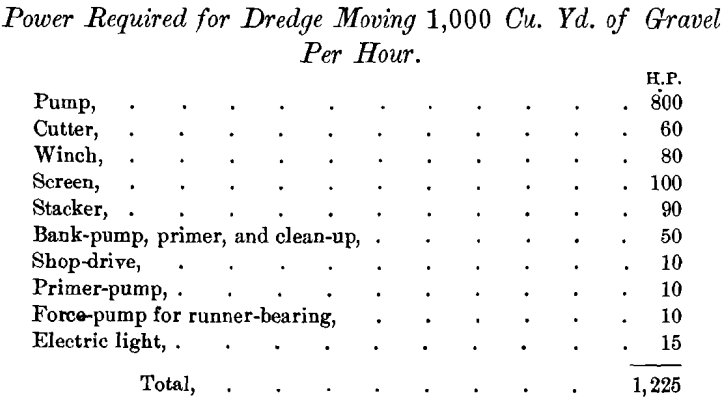

Power. The maximum power-requirements of a gold-dredge are estimated from the Steers dredge in operation, and proportioned according to the Oroville practice with dredges having a nominal capacity of 100 cu. yd. per hr. On this basis, the power-requirement would be:

Pump. In the opinion of Carl Lager, Superintendent of the Morris Machine Works, Baldwinsville, N. Y., which I adopt, with appreciation of his competent advice, a dredge intended to handle continuously gravel that would enter a 24-in. pipe would require a pump of cast steel, heavily reinforced and provided with manganese- or chrome-steel liners. The shell would need to be about 12 ft. in diameter by 4 ft. in width. The runner would be 7 ft. in diameter and make 170 rev. per min. The runner-shaft would have a slip-coupling, so that the runner might be stopped short by an obstruction without anything breaking. For dredging to a depth of 60 ft. the economical velocity of flow in a 24-in. pipe would be 10 ft. per sec., giving a flow of 14,200 gal. per min. If 23 per cent, of this flow was gravel, it would give the required 1,000 cu. yd. per hour. In practice, a skillful lever-man, working in free gravel, should raise 25 per cent, continuously. The outboard suction- pipe would be about 90 ft. long. For the less than 200 ft. of pipe required, the friction-head, at the estimated velocity of 10 ft. per sec, would, apparently, be less than 10 ft.; but, for safety, the total friction-head was assumed at 60 ft. and the pump-efficiency at 40 per cent., giving an estimated power- requirement of 600 h.p. delivered on the runner-shaft. The pump would discharge at one side of the bottom, and the discharge-pipe, before curving to the sluices, would have a removable section for taking out gravel in the event of a shut¬down under load. The pump would weigh about 65,000 lb., and cost not more than $10,000. For a reserve set of liners, $2,000 more may be allowed; and for an extra runner, $1,500.

Cutter. The cutter, to provide against breaking when stalled, should be driven by a 9-in. chrome-steel shaft, which should be supported by the trussed suction-pipe. Cast-steel pipe would probably be best for continuous gravel-suction. The suction-pipe and cutter, with drive and gears, would weigh about 70,000 lb., and cost about $9,000. The curve of the cutter-blades should be such as to leave the mouth of the pipe but a few inches above bed-rock when dredging at the full depth of 60 ft. The diameter of the cutter should be, say, 7 feet.

The Steers dredge has two large timbers as stiffeners to the suction-pipe and cutter-shaft, as shown in Fig. 1. It would be well to use, instead of these, two riveted hydraulic pipes, 24 in. in diameter, which would give a net buoyant effect of about

326 lb. per running foot, with the further advantage that the lengths of supporting pipe could be made exactly equal to the lengths of the cutter-shaft and suction-pipe, and, when desired, the whole ladder could be materially shortened or lengthened. These pipes and the cutter-shaft could be carried with advantage in a lattice truss, with a removable section, to permit permanent use at shallow depths.

Winch. Owing to the difficulty on the Steers dredge of throwing the cutter in and out of gear, it seems advisable to have the winches entirely separate. They should be very powerful machines, and, for gold-dredging in flowing rivers, would be found more satisfactory if divided into two units, one on each side of the dredge, each with a spool projecting, for warping, handling lines, etc. There should be 12 winch-barrels, of sizes proportioned to their respective services: two for headlines (one in reserve), which would be built to carry each 2,000 ft. of heavy steel cables; one for ladder-hoist; three for operating a snag-and-rock grab ; two for swinging-lines; two for stern-lines; and two for the spuds.

The winches should have gearing for two speeds: a very slow one for difficult situations, and a relatively fast one for ordinary circumstances. Extra lines would be an important part of this equipment. The total for this winch may be estimated at about $50,000, and a weight of 100,000 lb. should be allowed.

Bank-Pump and Clean-Up:

It will frequently be found desirable to cave the bank ahead of the dredge. The nozzle could be attached to the snag- boom, and handled close to the bank. The same pump would also answer as a primer, and to supply the amalgam-barrels and clean-up tanks; 50 h.p. would fill this requirement, A weight of 10,000 lb. and a cost of about $1,500 should be allowed for this item.

Force-Pump:

The force-pump to supply water under pressure to the main runner-bearing in the dredging-pump, would have to be running both before and after the dredging-pump was started, as. well as during dredging; 10 h.p. would cover this item, with about 700 lb. weight and a cost of $600.

Electric Light:

The dredge should be lighted throughout by electricity, with incandescent lamps handy to the machinery, two arcs at the bow, two arcs over tables, and one in the engine-room. Flaming-arc lamps should be used. A search-light should also be placed over the pilot-house, to be switched in when desired; 15 h.p. should cover this item, with a cost of $1,000 and a weight of 3,000 pounds.

Shop:

In connection with a large forge and blacksmith equipment, the dredge should have a lathe, shears, radial drill, and milling-machine ; also a traveler for handling the plates that would have to be constantly ready for the screen. It would be advisable to do this work on board, at least until the screen-requirements of a given district were standardized; 10 h.p. and a cost of $3,000, with a weight of 10,000 lb., should cover this item.

Stacker:

The capacity of the stacker should be such as to be able to handle a maximum of 10 cu. yd. per min.; length, say, 89 ft. A belt, running at not over 300 ft. per min., would seem to be the best to handle the gravel, without bringing too heavy a weight on the stern. A main belt, 60 in. wide, with the sides gently curved by idlers for 18 in. from the edges, and a superimposed flat belt to take the wear, should answer the purpose ; 90 h.p., a weight of 40,000 lb., and a cost of $10,000, should cover this feature.

Screen:

In view of the screen-areas of present dredges, and the record of the Sweetser-Burroughs dredge, quoted above, a screen with a surface of 2,000 sq. ft. would apparently be able to handle 1,000 cu. yd. per hr. The pipe would discharge, at 26 to 30 ft. above the water-level, into a stationary sluice, 25 by 20 ft. in size, with a bottom of 0.25-in. plate-steel, set at a grade of 0.25 in. to the foot and perforated with 1/8-in. holes, countersunk on the under side. This stationary screen would discharge, in turn, on to a shaking-screen of the same width extending over the rest of the length of the tables. The holes would increase in diameter to 0.5 in. at the lower end of the screen, and should be close enough together to make sure that all the water will drain through them before the gravel reaches the lower end. The shaking-screen would be set at a grade of 1.5 in. per ft., with an adjustable hanger for reducing the grade as desired, as shown in Fig. 2.

Gold-Saving Areas:

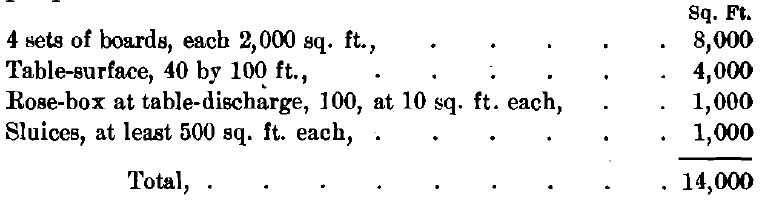

Dredges now in use have a saving-area of from 750 to 1,000 sq. ft. for a capacity of 100 cu. yd. of gravel per hour. This ratio should be at least maintained, and increased as much as practicable. It seems quite feasible to get a satisfactory area. The old Plutus and California, the first dredges in Oroville to use the shaking-screen (both steam-shovel dredges and long since abandoned), used a high drop of 2 ft. or more on to the tables, with the idea that the gold that fell with this impact would stay and amalgamate. But Vail, a veteran gold-sacver, argued that the gold which would stay by reason of its weight would stay anyhow, and that by utilizing this space for a riffle-board, having shallow auger-holes, he could provide a greater area to amalgamate the fine gold. His boards, set zig¬zag from the upper to the lower level, were successful; and, somewhat modified, they are used in some of the latest dredge. The following is the suggested gold-saving area for the dredge here proposed :

Hull:

For a field where the dredge would never have to move out of the reach of commercial electricity, and would not be compelled to carry long lines to work or warp against strong currents, the pump could be set in the center of the dredge, a much shorter hull could be used, and greater table-area secured by increased width. But for use in foreign river-bottoms, a hull 175 by 60 by 8 ft. would be better. The bow should be tapered and have a gentle rise for, say, 20 ft., and the stern should have an equal curve for the “ get-away.” The importance of the stern curve is sometimes not fully understood. Church has clearly shown that a blunt stern on a scow is a greater strain on a tow-line than a blunt bow, on account of

the great mass of water, the momentum of which it has to overcome.

Properly constructed of steel, with suitable wood-lined quarters for manager, captain, and crew, and adequate strength in every part for a sea-voyage, as well as for the strain of regular operation, the hull ought not to cost more than $45,000.

Fuel:

In New Zealand and elsewhere, dredges are operated with steam, using coal as fuel. But gold-dredges in South America would have to depend, at least for some time to come, on wood as fuel. Those who have been compelled to make steam with comparatively fresh-cut wood, wet by rain or by transportation in canoes, will probably agree with me that it is unsafe to estimate on maintaining 120 h.p. on less than 1/3 cord per hr., or 8 cords per 24 hr. At this rate, 1,200 h.p. for the proposed dredge would require 80 cords per day, which, under ordinary circumstances, would be a prohibitory condition.

The paper of Mr. Langton on The Power Plant of the Moctezuma Copper Co. at Nacozari, Sonora, Mexico, raises the interesting question of the use of gas-engines driven with gas from wood.

I am inclined to think that, under suitable circumstances, this means of generating power might be found practicable and profitable in some regions such as I have mentioned. But the source of power is a question of locality. In many places it would be best to utilize natural water-power through the electric current. For the proposed dredge, when electricity is not available, I suggest a marine producer-gas plant, as shown in Fig. 2, which, according to the Loomis-Pettibone Engineering Co., will deliver the required power with a wood-consumption of only 17 cords per day. The cost of such a plant would be about $12,000.

Engines:

Three gas-engines would be required: one for the dredging- pump, with four 20- by 25-in. cylinders, guaranteed to develop 700 h.p. at 170 rev. per min., and able to stand up under 1,000 h.p., though with somewhat less economy. This engine, including all auxiliaries, air-compressor, circulating-pump, etc., would weigh 40,000 lb., and cost $30,800.

The dynamo to distribute power to the various motors would be run by an engine with two cylinders (of the same dimensions, so that one repair set only need be kept), weighing 20,000 lb., and costing $15,400. This cost is stated to cover an extra cylinder set, extra one-half crank-shaft of total weight of 6,500 lb., and a 14 h.p. donkey-engine of two cylinders, with dynamo for lighting and pump, as well as a compressor for filling the air-tank for starting the large engines.

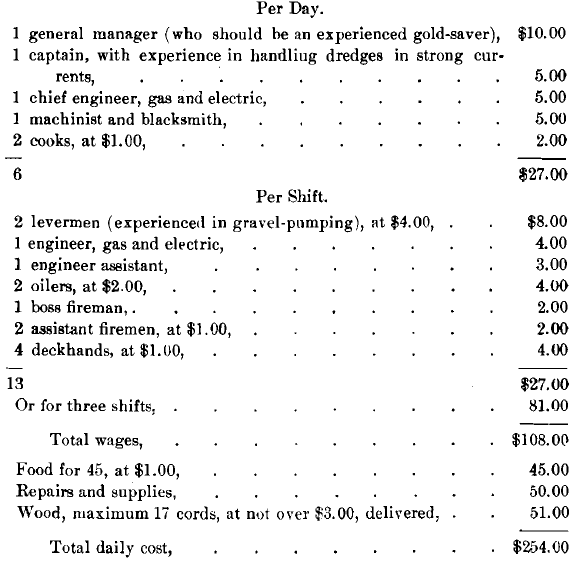

Crew and Expense:

For continuous operation and the occasional handling of heavy lines, the following crew should fill the requirements at the stated daily wage, plus food:

The allowance for food and wood is liberal, and a smaller crew would perhaps suffice; but these figures should not be cut for preliminary estimates.

Capacity and Cost Per Yard:

With ordinary care in painting and keeping up, a dredge built in the manner suggested should last many years. With all the machinery of the best character, a full supply of duplicates for all possible contingencies, a good crew and good management, the shut-downs should be but slight, outside of encountering snags and sunken logs, to handle which this hydraulic dredge would be as well equipped as any other. Very few stones would be found in the average dredging-field that would not go through a 24-in. ring, so there should be little time lost on this score. It seems entirely reasonable to expect to dredge 20 hr. per day. This, at 1,000 yd. per hr., would give a daily capacity of 20,000 cu. yd. of gravel.

Notwithstanding the smaller sum of the component items of cost given above, it would not be prudent to reckon that the cost of such a dredge, by the time it has been set up in the port of its construction, given a trial run, then housed and towed to its destination, and put at work on the ground, would be less than from $200,000 to $250,000. It should be remembered, however, that a dredge of this capacity and of the table- area to be used, and to employ commercial electricity as power, would cost less than half this sum, or no more than a good 7-ft. chain-bucket dredge.

A sinking fund, to retire $200,000 in 10 years, would require $83.29 per $1,000 per year, or per day (at 300 days per year), $55.53. This, added to the daily running-expense of $254, with a further allowance of $25 for general expense, gives $335 as the daily grand total; and this sum, divided by 20,000 cu. yd. of gravel handled daily, gives $0.01675 as the cost per cubic yard.

Even if the ground should be unusually full of logs, it is evident that considerable time could be lost without making the cost per yard excessive. In fact, the power of the dredge is so calculated that more than 1,250 cu. yd. of free gravel could be readily dredged and screened per hour, so that the assumed average of 1,000 cu. yd. per hr. can easily be maintained.

VII. Conclusion:

The design and specifications submitted in this paper are not offered as satisfying all conditions of gold-dredging. Many rich stream-beds would not give “ elbow-room ” for such a dredge: many otherwise favorable gold-bearing areas are too small to warrant the cost of its installation; and, in some localities, as I have already remarked, the supply of adequate power might be, at the present time, a matter of economically insuperable difficulty. But I believe that, under suitable conditions, the use of hydraulic suction-dredges of a minimum capacity of 1,000 cu. yd. per hr. would be exceptionally profitable; and I hope that my suggestions will elicit the discussion by engineers in this department of a proposition which, to my mind, promises so great an advance in this relatively new form of mining industry.

Several manufacturing concerns have been mentioned, as a matter of record, in the foregoing pages; but I need hardly say that these references are not intended either to advertise particular parties, or to convey the impression that these parties only would be able to furnish the machinery contemplated. On the contrary, there is nothing in the design here proposed which could not be constructed by any establishment experienced in such work.

Hydraulic Dredging for Gold-Bearing Gravels BY HENRY G. GRANGER, CARTAGENA, COLOMBIA