Here is an Ancient Gold Ore Milling Process used in China in the 1800s. We might use it again after WW3.

At the time, 1890, the Author said “There is, of course, nothing for us to learn from this imperfect and rudimentary gold-extraction process described here, which is doubtless destined to disappear ere long, before the progress of scientific mining, now making itself slowly felt throughout the far East. I think it advisable, however, to put on record all such crude efforts, if only to enable us to trace more completely the evolution of our modern systems of mining, and to teach us by what widely-divergent methods different races of mankind have attempted to solve one, apparently simple, problem.”

Their method of mining was then, and is now, the following: A small water-furrow is first brought in at the highest possible level on a suitable hill-side, and the stream is turned down the hill. By means of a heavy long wooden crowbar, shod with a long strongly- made chisel-pointed iron socket, and with the help of the stream of water, which rarely exceeds 50 cubic feet per minute, the surface- soil and weathered country-rock are loosened and sluiced away. No trouble is taken to save any of the gold washed down, except in one or two instances where rude riffles have been inserted in the tail-race; the race is, however, carefully searched for bits of quartz showing visible gold, which are picked out and put on one side. The surface of the shales is thus stripped, and any veins of gold that may be laid bare are then worked. The principal mining- tool is a rough kind of pick, and the use of explosives, or even of wedges, is quite unknown. Neither shovels nor barrows are used ; their places are taken by broad hoes and baskets, a pair of the latter, swung at each end of a stick and holding at least 70 pounds, being easily carried up steep grades by a Chinese miner. The tunnels, small and irregular, usually incline steeply upward ; they are rudely timbered, and as timber decays rapidly in this climate, these workings cannot penetrate far into the hills, but soon have to be abandoned, and the whole series of operations has to be recommenced.

A party of 27 miners, who owned and worked a rich hillside, considered themselves to be doing well when their entire day’s output (they do not work night-shifts as a rule) was a little over half a ton of quartz. The quartz, as extracted from the reef, is cobbed down with hammers to about pass a 1 J-inch ring, and is then carefully hand-picked, all stone showing visible gold, sulphurets or any other favorable indications being sent to the mill and the rest being thrown away. From one-eighth to one-half is thus rejected. I have assayed many samples of this refuse rock, which carries from 3 to 10 pennyweights of free milling gold to the ton, so that it is quite worth milling according to our modern ideas.

At first the mode of crushing adopted by the Chinese consisted in heating the rock red-hot, quenching it in water and then pounding it down and rubbing it between two stomps. About 35 years ago a tilt-hammer, made entirely without iron and having a stone head, was introduced, and is still much used by individual miners. About twelve years ago the battery of three to six hammers, worked by a water-wheel, was first employed. It is said to have been copied from mills for crushing the materials of “joss-sticks.” Tilt-hammer rice-mills are also built. Such water-mills are usually the property of a party of miners working together.

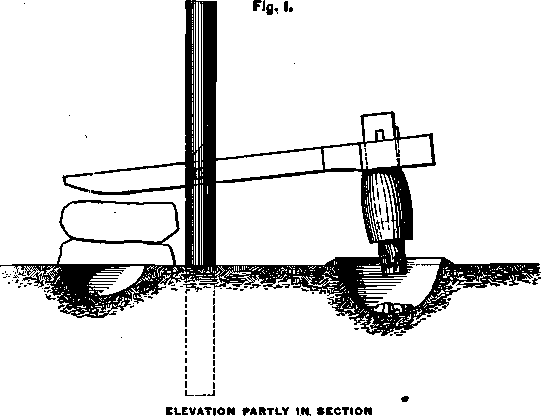

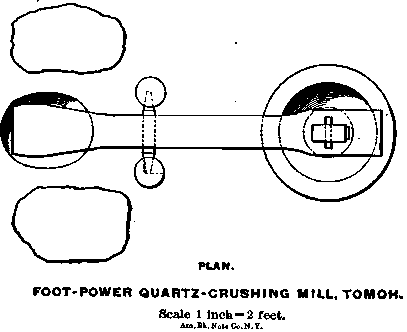

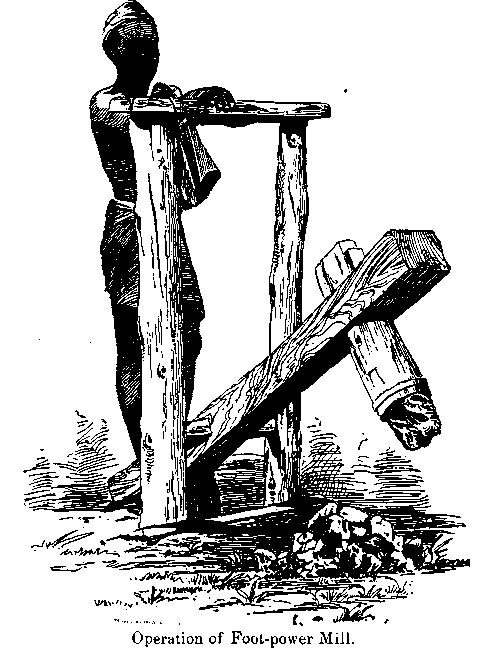

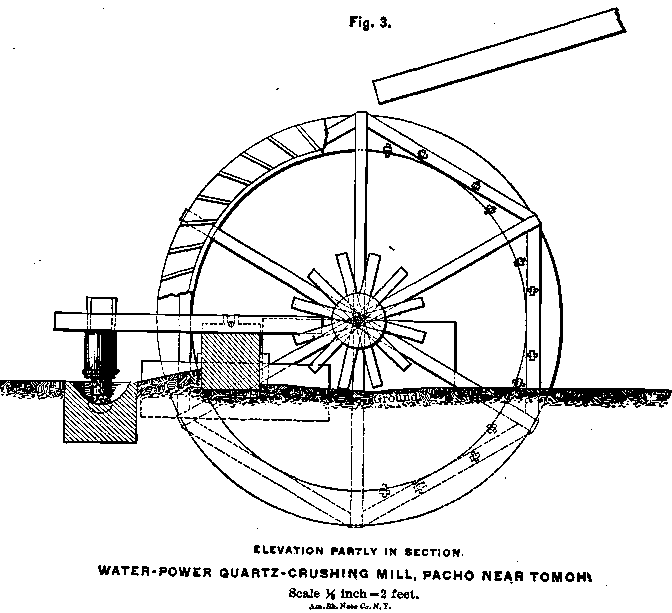

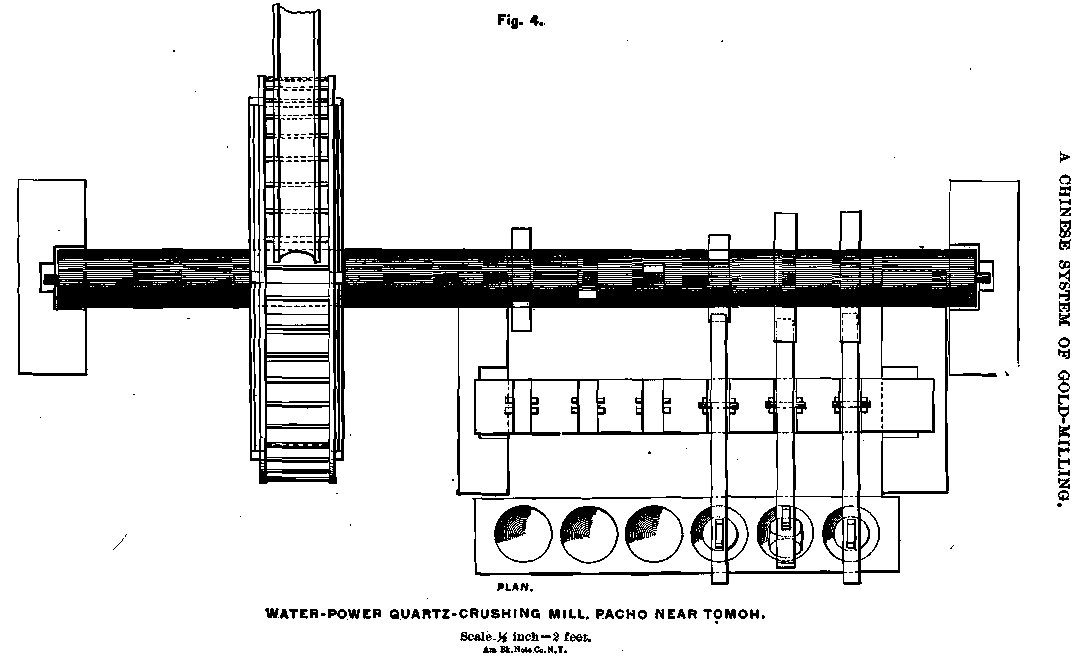

Here is described the method of milling with both the foot- and the water-mill, a typical pattern of the former being shown in Figs. 1 and 2 and of the latter in Figs. 3 and 4.

The foot-mill shown in Figs. 1 and 2 is of the usual type, from which there are but few unimportant departures. The entire falling weight is about 45 pounds, and the length of drop about 20 inches; as a rule, these mills are worked at 15 to 20 blows per minute.

The mill shown is built entirely without iron; the stone that forms the base of the mortar is a piece of hard quartzite or of barren reef-quartz, the same material being used for the hammer-head, which is firmly held in its socket by wooden wedges, the socket being kept from splitting by a stout hoop of rattan twisted round it. Some of the mills use iron hoops, and some have iron spindles for the hammer to work on; with these exceptions and one or two other very unimportant details, the construction is always the same, though the dimensions may vary a little. There is scarcely a house in the whole district that has not one of these mills.

The Chinese usually work these mills for about eight hours per day. A shovelful of quartz is first thrown into the mortar and the mill is then worked by the foot of the miner, who stands on one or other of the stones shown in the drawings, grasping the uprights or else a cross-bar that is sometimes fastened across them.

When the quartz is supposed to be crushed sufficiently fine, the hammer-head is propped up, and the crushed stone is scraped out and sifted through a circular sieve 15 inches to 20 inches in diameter, and about 1J inches deep. The sieve itself is made of thin strips of rattan about 0.1 inch in width. There are from 36 to 40 holes per square inch, so that the width of mesh varies between 0.04 and 0.06 inch. A man can crush in a working day, with one of these mills, from 70 lbs. to 140 lbs. of stone, according to its hardness.

The number of heads in a power-mill varies between 3 and 6, depending principally on the quantity of water available. As the district is well watered, the large majority are 6-stamp mills; out of 11 power-mills which it contains, 8 are 6-stamp mills. Figs. 3 and 4 show the usual type of the latter mills, from which pattern there is practically no departure. I could not even induce the Chinese to try a curved cam instead of a straight one, as they seemed to consider such innovations dangerous ; and they added that “ wood and water were both cheap enough.” As will be noticed, the construction of the water-wheel is extremely crude—the water, which is sometimes brought down very steep hills from considerable heights in small, highly-inclined ditches, strikes the flat buckets with considerable velocity, so that the wheel is partly an impact and partly a pressure wheel; the buckets are never more than half-filled at the best, and the wheel is sometimes allowed to wade in tail-water to the full depth of the shrouding. Much power is accordingly wasted, the amount of water consumed in driving one of these mills being from 80 to 100 cubic feet per minute.

The number of heads in a power-mill varies between 3 and 6, depending principally on the quantity of water available. As the district is well watered, the large majority are 6-stamp mills; out of 11 power-mills which it contains, 8 are 6-stamp mills. Figs. 3 and 4 show the usual type of the latter mills, from which pattern there is practically no departure. I could not even induce the Chinese to try a curved cam instead of a straight one, as they seemed to consider such innovations dangerous ; and they added that “ wood and water were both cheap enough.” As will be noticed, the construction of the water-wheel is extremely crude—the water, which is sometimes brought down very steep hills from considerable heights in small, highly-inclined ditches, strikes the flat buckets with considerable velocity, so that the wheel is partly an impact and partly a pressure wheel; the buckets are never more than half-filled at the best, and the wheel is sometimes allowed to wade in tail-water to the full depth of the shrouding. Much power is accordingly wasted, the amount of water consumed in driving one of these mills being from 80 to 100 cubic feet per minute.

The average number of drops of each head varies between 27 and 32 per minute; the length of the drop is about 2 feet, and the effective falling weight of the head is about 70 lbs. Thus only about one-third of the theoretical power of the water is utilized, but of course much of this loss of energy is due to the friction of the whole machine, notably between the straight cam and the tailpiece of the hammer. There are usually 3 men per shift working one of these mills, 2 being engaged in looking after and feeding the machine, while the third sifts the pounded stone as already described, throwing back under one of the hammer-heads whatever will not pass the sieve.

The cost of one of these mills complete, including a substantial shed over it thatched with palm leaves, but excluding the water- furrow, is said to be about “very little”, and they are supposed to last from 5 to 7 years—needing, however, constant repairs.

A stone hammer-head lasts from a week to a month, according to its quality. They are made, as in the foot-mills, from boulders of quartz rock, and it is mostly one man’s business to search for these boulders in the bed of the stream, and, when found, to dress them into shape.

The crushing capacity of one of these mills varies from 850 lbs. to 1400 lbs. per 24 hours, according to the hardness of the rock. It is to be specially noted that the crushing is performed quite dry.

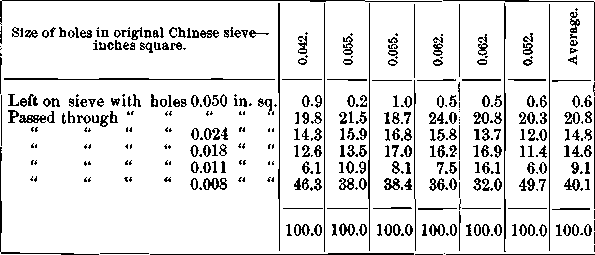

I tested the degree of fineness to which these mills reduce the quartz by differential siftings of a number of samples, taken by spoon-sampling the heaps of crushed ore lying at various mills. The results of some of my tests are given in the following table :

It appears from the above table that a great deal of the ore is crushed very fine (too fine, indeed), while some is not fine enough. As about 40 per cent, of the ore will pass through a 6,400 sieve, there must be much over-stamping, resulting, no doubt, in the production of a great deal of float-gold and slimes.

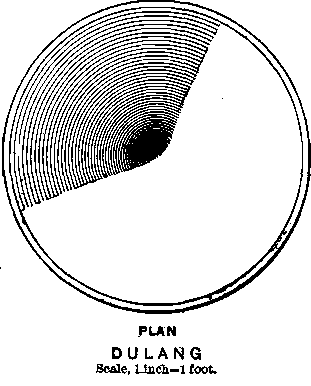

After the mill has been running for a longer or shorter period, according to circumstances, a clean-up takes place. The crushed ore is carried out in large wooden pails to a Chinaman, who washes it, squatting down by the side of a square pit, through which a small stream of clear water is kept running. The implement used for washing is a flat, somewhat conical wooden dish, cut from the spurs of certain hard-wood trees, and fashioned with much care. It is known as the dulang, and much resembles the Spanish-American batea, except that the section of the former is that of a very obtuse rounded cone, while the section of the latter is approximately that of a sphere.

A section of a typical dulang is shown in Fig. 5. Much importance is attached to the correct shape of the conical point, as it is in this that the precious metal is gathered together. The dulang is filled with from 10 to 15 lbs. of crushed stone, according to its size, and this is washed by a curious circular, combined with a slight undulatory motion, by which the particles of light, barren quartz are swept over the edge of the dulang, which is held just dipping below the surface of the water in the pit, while the heavier particles are collected in the rounded apex of the cone. When nearly cleaned, the gold and concentrates are transferred to a smaller, very carefully made and polished dulang, about 1 foot in diameter, in which the quartz is washed off as thoroughly as possible, and the gold, by a skillful jerk, is thrown clear from the sulphurets, and finally collected in a small brass dish. The sulphurets still retain much coarse gold, to which they cling obstinately. They are ground as fine as possible on a stone and re-washed several times, a good deal of the gold being thus separated and added to that previously obtained. Even then the sulphurets still carry much gold, the larger portion of which is free. They are stored away in jars while wet and allowed to rust, and after a time they are sometimes re-crushed and re-washed ; very often, however, they are merely allowed to accumulate and are not treated further. The first tailings are re-washed, and then stacked.

The cleaned gold is dried and melted over a small forge provided with a box-shaped wooden blower of the usual Chinese type. The fuel is charcoal. Tiny, conical crucibles, capable of holding about a couple of ounces of gold are used; the gold-dust is melted in these with borax and niter as fluxes; the slag is lifted off the surface of the gold when the latter is supposed to be clean, by means of an iron rod, and the gold is then granulated by pouring into water. If it is not considered to be sufficiently soft and pure it is re-melted, and the process is repeated until the gold is quite soft. The principal impurities removed seem to be sulphur, arsenic, a little copper, and perhaps traces of lead. Both the granulated gold and the crude gold-dust, as also gold got from river-washing, are used as currency in this district, coined money being scarcely ever seen here, and then only in the form of the old dollar.

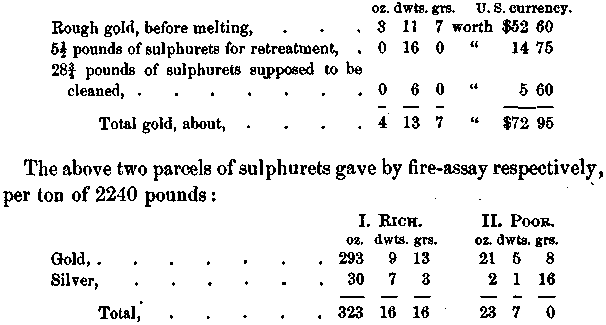

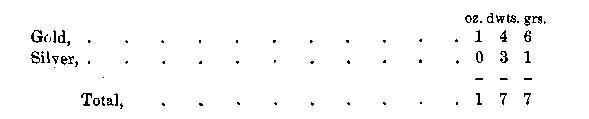

In a partial wash-up at one of these mills, during my stay in the district, the following results, considered to be exceptionally good, were obtained, the quantity washed being as nearly as possible 2000 pounds of crushed ore:

The tailings from this (or a similar) washing gave by fire-assay, per ton of 2240 pounds :

As a general rule, there seems to be left in the tailings about one- third of the gold originally present in the ore, while there must be a considerable additional loss of float-gold carried away in the process of washing, due to the original fineness of some of the gold in the ore, and to the over-stamping already referred to.

The Chinese themselves seem to be of opinion that they get about one-half of the gold originally contained in the stone.

The following examples will show how much gold is retained in the tailings:

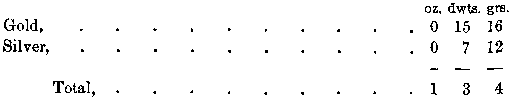

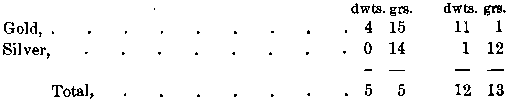

In working a very rich ore, which assayed, per ton of 2240 pounds, the tailings, after three times pounding and washing, still assayed:

thus showing that nearly one-half of the proportion of gold originally present was still locked up in the tailings.

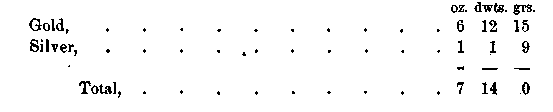

In another instance, where the quartz assayed originally:

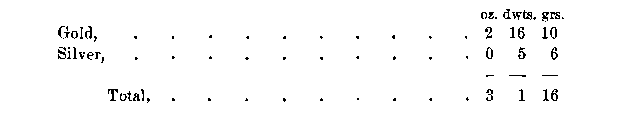

two piles of tailings, both said to have been exhausted by five or six poundings and washings, assayed respectively: .

From the average of these two assays it would appear that nearly one-third of the original proportion of gold is still left in the tailings. I might quote numerous other assays, but the results in all cases were approximately the same; there were no really clean tailings at all, in spite of the fact that they were all the result of handling sur- face-ores, where practically the whole of the gold was free. The losses above indicated appear enormous, but it must be remembered that the thrifty Chinamen throw nothing away—not even tailings; however completely, in their opinion, these may be exhausted, they still pile them up and keep them. When, for any reason, their mill would otherwise be idle, they re-pound and re-wash their old tailings, and always get some gold out of them. The piles of tailings are, however, left exposed, so that a considerable proportion gets washed down into the streams and rivers by the heavy rains that occur at each change of monsoon ; and there are a good many Chinese of the poorer classes who make a sort of living by washing the sands in the river-beds, the gold they get being principally, to all appearance, that which has been thrown into the rivers by the miners up stream. It is noticeable that there is no gold, or very little, to be found in the rivers above the points where there are mines in operation. A fair day’s work of one Chinaman in the river-bed (say six hours’ actual work) was found, as the average of several trials, to produce an output of 7.3 grains of gold about .940 fine, worth say little in local currency. This quantity of gold was obtained by washing 22 large dulangs of gravel, each holding about 70 pounds of dirt.From the average of these two assays it would appear that nearly one-third of the original proportion of gold is still left in the tailings. I might quote numerous other assays, but the results in all cases were approximately the same; there were no really clean tailings at all, in spite of the fact that they were all the result of handling surface-ores, where practically the whole of the gold was free. The losses above indicated appear enormous, but it must be remembered that the thrifty Chinamen throw nothing away—not even tailings; however completely, in their opinion, these may be exhausted, they still pile them up and keep them. When, for any reason, their mill would otherwise be idle, they re-pound and re-wash their old tailings, and always get some gold out of them. The piles of tailings are, however, left exposed, so that a considerable proportion gets washed down into the streams and rivers by the heavy rains that occur at each change of monsoon ; and there are a good many Chinese of the poorer classes who make a sort of living by washing the sands in the river-beds, the gold they get being principally, to all appearance, that which has been thrown into the rivers by the miners up stream. It is noticeable that there is no gold, or very little, to be found in the rivers above the points where there are mines in operation. A fair day’s work of one Chinaman in the river-bed (say six hours’ actual work) was found, as the average of several trials, to produce an output of 7.3 grains of gold about .940 fine.

It is interesting to note that in custom-milling, of which there is a good deal done here (many of the “ fossickers ” sending all the gold quartz they collect, whether by mining or picking out of the river- gravels, to one of the water-mills for crushing), the charge made is equal to just a few $U. S. per (long) ton of quartz, this payment including the washing of the gold, but not, so far as I can make out, its cleaning and melting.

It is obvious from the above description, that the total quantity of stone crushed by all the mills in the district, supposing them all to be going simultaneously, and including the foot-mills, could not exceed some 12 tons a day at the best, an amount that could be far more economically and efficiently handled in a five-stamp Californian mill of moderate power. Yet the total annual output of gold from this district (including, however, alluvial as well as reef-gold) is said to be 4861 ounces, fully .900 fine. The total number of men engaged in mining, in one way or another, is close upon one thousand.

HENRY LOUIS, ASSOC. R.S.M., F.I. C., F. G.S., ETC., SINGAPORE, STRAITS SETTLEMENTS.