Table of Contents

The type of a Dredge is defined according to the Nature of the Work they do. Under this heading bucket dredges may be classed as: River dredges; paddock dredges.

The river dredge is designed to work with some depth of water underneath it, and is not called upon to cut its own flotation. It is, therefore, not provided with a projecting ladder to eat into banks, nor with sharpened bows to work into corners; but, as a rule, is built square across the bows, especially if working in a current such as runs in the Molyneux in New Zealand, for the practice there has proved that a square-nosed dredge remains steadier in the current, and does not “ yaw ” about so much as a sharp-nosed one. Of course, square bows offer much greater resistance to the current and require heavy lines to hold them, but as a dredge is not built for speed, resistance is not taken into consideration to any extent beyond the usual practice of making the floor of the pontoon take an upward curve at the bow.

A paddock dredge should draw as little water as possible, and the draught should not exceed 5 ft., even in large dredges; a fair average draught is about 3½ ft. with twenty-four hours fuel on board and the dredge gear. The bows of a paddock dredge should be well rounded to permit of being easily manipulated in a corner, and should also be more heavily planked and framed than the other pontoons, so as not to be damaged by striking a face, as the dredge surges at her work. Very often the bows are sheathed with steel plates as a protection against blows and chafing. The bottom of the hull at the forward end should be sprung or bevelled upwards for clearance and handiness in working, and the bottom from the bows aft to the position of the ladder at the “ maximum dredging depth ” should have the thickness of planking considerably increased to obviate accidents through logs being caught in the buckets, and by their being dragged upwards through the bottom. This type of accident is by no means infrequent.

The principal dimensions of the “Werf Conrad” Paddock bucket Dredger, as illustrated, are:

- Length, 28.80 m.

- Breadth moulded, 9 m.

- Depth, 1.35 m.

- Draught, ± 0.75 m.

- Dredging depth, o to 7 m.

- Output per hour—

- In hard material, 50 m³

- In light material, 70 m³

- Total engine power, 80 i.h.p.

- Heating surface of boilers, 60 sq. m.

- Total surface of tables, ± 50 sq. m.

The following is a description of the Earnscleugh No. 3 Paddock Dredge:

The dredge is the ordinary bucket type, electrically driven, with dimensions as follows:

- Length of hull, 130 ft.

- Width of hull, aft, 34 ft.

- Depth of hull, aft, 7 ft. 6 ins.

- Width of hull, forward, 26 ft.

- Depth of hull, forward, 5 ft. 6 ins.

- Length of main ladder, 90 ft. between centres.

- Capacity of buckets, 7 cubic feet.

- Speed of buckets, 9½ per min.

- Lift of dirt from deck to centre top tumbler, 17 ft. 6 ins.

- Lift of water, 17 ft. 6 ins.

- Diameter of centrifugal pump, 12 ins.

- Diameter of screen, 7 ft. (friction driven).

- Length of screen, 30 ft. (friction driven).

- Length of tables, 24 ft.

- Width of tables, 16 ft., giving a spread of 384 sq. ft.

- Diameter of silt-wheel, 12 ft., 4 revolutions per minute.

- Width of silt-buckets, 10 ins.

- Depth of silt-buckets, 6 ins.

- Length of elevator-ladder, 128 ft. centres (bottom drive).

Winches—worm and friction-wheel type—driven by 20 h.-p. motor. Buckets, pump, screen, silt-wheel, and elevator all driven off a shaft extending the full width of the dredge, with the necessary belts, pulleys, and gear-wheels, by a 100 b.h.p. motor. The dredge is floating about 20 ft. from the surface, and takes three to four heads of water running into the paddock to keep it at that level. When first started, the dredge stood 50 ft. above the level of the Molyneux River, a quarter of a mile distant The dredge was built in a hollow on a terrace adjoining the Earnscleugh Nos. 1 and 2 Claims, and, when ready, was floated by means of a water-race being turned into the dam.

The necessity for paddock dredges grew out of this condition; the high bars and gulches were worked by ground sluicing and hydraulicing because there was enough grade to carry the water and tailings down hill, away from the work. But down below these high bars and gulches were larger valleys containing gold-bearing gravel beds, in which there was not enough grade to carry off the tailings. These latter gravel beds are very extensive, and generally richer in gold. In order to sluice this material, it was necessary to dig it, and then lift it to a height which would give the requisite grade for properly working the material. The dredge does this. It is a self-contained machine which scoops out and lifts the material, screens out the large boulders and coarse rocks, and then sluices the material with the water which it raises with its own pumps.

The curious feature of this form of gold dredging is that the dredge floats in an artificially made pond, and then carries the pond along with it. After the prospector has located the gold-bearing gravel deposit, and the experts have satisfied themselves that the gold is there, the timber and machinery for building and equipping the dredge are assembled. Sometimes the point of attack is within easy reach of a railroad. Sometimes it is a hundred or more miles from the rails in some wild canyon. In either case, there must be water which can be pumped or brought to the place through pipes or a ditch. With wheeled scrapers and other forms of dry excavators a shallow pit is dug, and on the dry bottom of this waterless pit the pontoon or hull of the dredge is constructed, and while the boat-builder is at work other men are digging the ditch or laying the pipe to bring the water to the dredge. When the water arrives the pit is filled, and then the dredge is afloat in a pond some 150 to 200 ft. wide by about 200 ft. long, where no pond was before. This pond is a movable pond, for when the dredge is working it excavates in front and fills in behind, so that in time the pond is a considerable distance from its original site.

According to the Motive Power

According to the motive power employed, bucket dredges are termed:

- (a) Current-wheeler dredge;

- (b) Steam dredge;

- (c) Electric dredge;

- (d) Turbine dredge;

- (e) Pelton-wheel Dredge

(d) Turbine Dredges.—The author knows of only one instance in which a dredge was worked on this principle. About 1889—90 Messrs. Kincaird & McQueen, of Dunedin, constructed for the Ocean Beach Lagoon, West Coast of Middle Island, a bucket dredge worked by a turbine-wheel. The water was brought from a creek in wrought-iron pipes, but on trial the pipes proved faulty, and the turbine was replaced by steam power.

(e) Pelton-wheel Dredges.—At Waipori and Cardrona, Mr. W. Obrien adopted water-power direct for working a small dredge. A Pelton wheel, from which the machinery is driven, is mounted on the dredge. Water under pressure is conveyed in pipes, and, to allow of the movement of the dredge without interfering with the water supply, the pipes between the dredge and the bank are carried on small pontoons, and have ball joints. By this means the varying movements due to height of water and shifting of dredge are met. The disadvantages of wear and tear of the joints might be, and, it is said, have been, removed by the use of armoured hose. The advantages claimed are that engines, boilers, and fuel, with their attendant costs, are dispensed with, and the water used for the Pelton wheel, which is placed at the same elevation as the sluice boxes, is afterwards utilised for washing the material, thereby obviating the necessity of pumping water for this purpose. A small reversible wheel is used to work the winches. On a 3¼ c. ft. capacity bucket dredge running at about 13 buckets per minute, the substitution of water for steam power is stated to have effected a saving of £1,000 per annum.

Types of Dredge

A type distinction between bucket dredges is sometimes drawn, the two classes being respectively termed the New Zealand and the American. The New Zealand type of dredge is said to lift the material higher and to screen it finer than the American, and, consequently, to be more costly in operation; and, while the former type is maneuvered by lines alone, the latter employs also the spud, by which greater steadiness in work is obtained. The New Zealand dredge largely employs tables for gold saving; but the American relies chiefly on the riffled sluice and is therefore simpler in operation.

“ The type of dredge,” says Mr. R. L. Montague, “ that is so successful in America is in its main features totally different from the New Zealand type of machine. In the former, the gravel in place is excavated by an endless chain of buckets; in some instances the buckets are connected by links, in others the buckets are continuous. The upper tumbler which drives this chain of buckets is set about 14 ft. above water level. The excavated gravel is dumped into a grizzly placed with its lower end projecting over the side of the boat; and the large boulders drop overboard, and are thus easily disposed of. The finer material that passes through the openings in the screen (these openings average inches square) falls into a sump, and a centrifugal pump picks up this gravel, together with the water necessary to sluice it, and elevates it into a sluice box, which is supported on an auxiliary flat boat at the stem of the dredge. It is not necessary to have the upper end of the sluice-box over 20 ft. above water level; the average height taken from a number of dredges operating in various localities is 15 ft.

“ This type of dredge, instead of being held in position by a series of wire cables, is held by means of a ‘ spud ’ or anchor, which consists of a timber shod with a steel shoe, or, as is the case in some places, the spud is made up of sheets of steel and channels, I beams, &c. The digging is performed by starting the bucket-chain on one side of the face of the cut, and moving slowly across the face. As the dredge is pivoted on a spud at the stem, only one line is needed to swing the dredge. When the other side of the face is reached, the ladder supporting the bucket-chain is lowered, and the dredge swung slowly back, thus taking off another cut. This process is kept up until bed-rock is reached; then the dredge is moved up towards the face, and the process is repeated. There are several advantages in this method of digging that appeal to a practical man. One point is that the cut is dug out clean, it being impossible to leave any gravel behind. Then, again, the dredge being held steady by the spud, there is practically no surging backwards and forwards of the dredge, as is the case with dredges that are only held by cables. The side-feed makes it easier to keep the buckets full continuously, and, furthermore, cleans bed-rock better than any other method of digging. The only parts of this dredge that are brought in contact with the gravel are the bucket-chain, the revolving screen, and the centrifugal pump.

“ The upper end of the sluice box rests on a turntable, the base of which is supported on the dredge; and a short length of special hose connects the end of the discharge pipe, from the centrifugal pump, with the sluice. By this means, a flexible connection is formed between the dredge and the sluice-box. The lower end of the sluice can be swung into any position, and thus the accumulation of tailings can be regulated and spread evenly across the pit.

“ A further advantage of this method of dredging is that the coarse material, being on the bottom and the fine material running on to it, fills up all the spaces between the boulders, and thus packs the tailings well down. The actual space occupied by tailings from a cut, the average depth of which was 35 ft., was 38 ft.

“A properly-designed sluice-box boat will have 50 ft. clearance between the dumping end of the sluice and the stem of the auxiliary flat boat which supports it. This ensures against the tailings crowding in and grounding the sluice-box boat.

“ In the New Zealand dredge the upper tumbler is set about 22 ft. above water level; the excavated material is dumped into a revolving screen with very fine openings. The screened material is carried over a set of gold-saving tables extremely limited as to size, and then elevated by means of a centrifugal pump. The coarse material that comes out out of the lower end of the grizzly is about 24 ft. above water level. While it is true that it is not necessary as a rule to run the centrifugal pump that lifts the fine material from the gold-saving tables continuously, we can safely say that this pump is run half the time.

“ I will now compare the work done by the two different types of machines.

“ The American type lifts 100 per cent, of the material 14 ft. above water level, and after screening lifts, say, 60 per cent., 15 ft. above water level. The New Zealand type lifts 100 per cent, of the material 22 ft., and after screening lifts 60 per cent 24 ft, and 40 per cent. 24 ft. for half the time. The ratio of power expended in lifts alone is 23 :42.2.

“ In the American type I have put the screened gravel at 60 per cent, of the whole, and as the openings in the screen of the New Zealand type are so much smaller, I have put this dredged screened material at 40 per cent, of the whole (note, the smaller this percentage is, the more unfavourably does the ratio work out).

“ From actual experience I find that an American type dredge, with a chain of buckets of 5 cubic feet capacity, will excavate and sluice on an average 2,300 cubic yards per day of 24 hours. The indicated h.-p. of this dredge was 120. This dredge was driven by electric motors, and the instruments used to measure the power were made by a first-class firm—viz., the Weston Instrument Company, Newark, N.J. This works out at about 19 yards per h.-p. per day. The work done by the New Zealand type I cannot state from actual experience, but taking the figures that have been given me by the advocates of this type—viz., 50 h.-p. for a 3-ft. bucket dredge, the capacity is 600 cubic yards per day on an average. This works out at 12 cubic yards per h.-p. per day. In buying electric power by meter rate, we will presume that a unit of h.-p. costs £1 ($5) per month. The wages we will put at 10s. per day unskilled, and 14s. and 16s. per day for skilled labour.

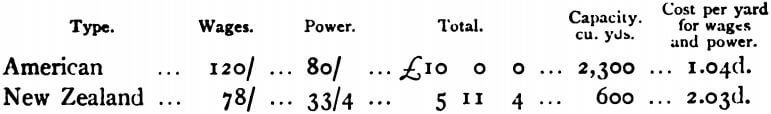

“ The American type will need per shift of eight hours one operator at 16s., one machine tender at 14s., and one deck hand at 10s. The New Zealand dredge will need one operator 16s., and one deck hand at 10s. The total wages and power bill per day will be: American type—wages 120s., power 80s. per day; total, £10 per day. The New Zealand dredge—wages 78s., power 33s. 4d.; total, £5 11s. 4d.

“ Obviously, the American type of dredge can handle ground more economically than the New Zealand type. When we go into the cost of repairs the comparison is still more unfavourable for the New Zealand type.

“ In drawing these comparisons, I have had, on one hand, my own experience as the source of my figures; but, on the other hand, I have had to take figures of those who were interested in the New Zealand type of dredge.

“ In regard to the gold-saving efficiency of the American type of dredge, in localities where the gold is coarse no difficulty is experienced, and in other places where finer gold is met with, the introduction of under-currents in the sluice and other devices has successfully accomplished that end.”

The author thinks that the above comparison is not altogether fair to the New Zealand dredge. Many engineers believe that, for general work, the resiliency given by the New Zealand use of the headline is of material benefit, by reducing the jars or shocks that the dredge must suffer when rigidly held in position by the spud which allows no give and take. There is also little doubt that the New Zealand system admits of more rapid change of position, since there is no delay in resetting a spud. Again, the system enables the stem of the dredge to be moved independently of the bow. As regards power consumption, it must be remembered that the chief expenditure is, not in lifting the material, but in overcoming the friction of the bucket-belt over the two tumblers, and in actually digging out the gravel. As the belt friction is largely independent of the height of lift, and the power expended in excavating is no function of the lift, the comparison as to power consumed can hardly be so much in favour of the American type as Mr. Montagu contends. It appears also as if in the comparison of costs, maxima had been selected for the New Zealand and minimal for the American dredge. The selection of gold-saving appliances is not a question of type, but of suitability to the character of the gold.

DREDGE TYPES

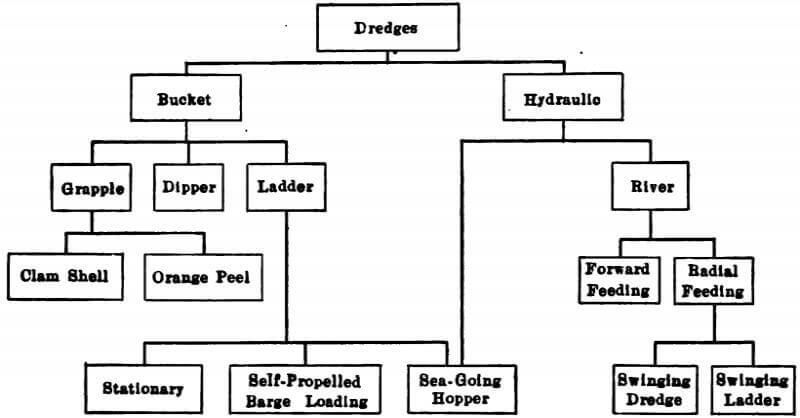

A dredge is a floating excavating machine, and the process of removing subaqueous material is termed dredging.

There are many kinds of dredges and several classifications are possible, differing in the choice of a basis of distinction. It is the author’s intention to discuss only the more important types, the usual equipment of to-day, disregarding the older and practically obsolete plant such as stirring and pneumatic dredges. With this limitation, dredges may be classified broadly under two general heads:

- Bucket Dredges

- Hydraulic Dredges

Bucket Dredges, obviously, are machines that remove the material by means of buckets, which, after obtaining their loads by biting or digging into the bottom, are raised clear of the water to dump either into waiting scows, self-contained hoppers, or upon spoil banks.

Hydraulic Dredges, known also as Suction or Pump dredges, excavate by direct centrifugal pumping through suction pipe, pump and discharge pipe into hoppers contained in the dredge itself, into hopper barges, into adjacent deep water, or into natural or prepared reservoirs, called impounding basins, from which the great volume of water, necessarily pumped along with the dredged material, runs off, leaving a deposit of solid matter.

The bucket class may be sub-divided into three types:

(a) Grapple Dredges

(b) Dipper or Scoop Dredges

(c) Ladder or Elevator Dredges

Both Grapple and Dipper machines have a single bucket each. In the former, it is suspended from the end of a swinging boom and consists of two or more shells or jaws, by the closing and opening of which the bucket is loaded and discharged. In the latter, it is a scoop attached to a long handle and “digs” in the same manner as the familiar steam shovel on land.

Ladder Dredges consist of a series of smaller buckets travelling in endless chain succession upon an inclined frame called a ladder, in passing under the lower end of which they receive their loads by scraping along and into the bottom, discharging into a chute while passing over the upper tumbler. Apparently it is simply an application of the old principle of the bucket elevator.

Grapple or Grab Dredges, in turn, may be divided into two sub-types:

(a) Clam-shell Dredges

(b) Orange-peel Dredges

A distinction only by virtue of the style of bucket carried. A clam-shell bucket has two quadri-cylindrical shells arranged in a manner sufficiently analogous to those of the more humble clam to warrant the pilfered title. An orange-peel bucket has generally four shells, forming a hemispherical bowl when closed, but spreading when open like the quadrants of an half orange.

Ladder Dredges are susceptible of sub-division into three classes:

(a) Stationary Dredges

(b) Self-propelled, Barge-loading Dredges

(c) Sea-going, Hopper Dredges

The first is the usual river or calm-water type, which is fed laterally or radially by means of anchorages or spuds and hauling cables, and discharges either into waiting barges, or into deep water or spoil basins more remote from the dredge.

Both the second and third types have moulded hulls and sea-going qualities, but the second, because of the accompanying barge, is confined to the calmer waters of ports and estuary channels, while the third is a sea-going vessel, comprising both barge and dredge in one.

Hydraulic Dredges are of two general types:

(a) The River Dredges

(b) Sea-going Hopper Dredges

There are two principal River Types:

(a) Radial Feeding with Spud Anchorage

(b) Forward Feeding or Mississippi River Type

Again, Radial Feeding Dredges may be either of the Swinging Dredge Type or the Swinging Ladder Types. In the former, the dredge itself pivots about a stern spud, and in the latter, the ladder only pivots about the bow of the dredge, which is held stationary by four spuds.

The subdivision of Hydraulic Dredges might be carried still further with self-propulsion as the distinguishing feature, as both Radial and Forward Feeding Machines have been built to navigate under their own motive power. They, however, are the exception rather than the rule and would result in unwarranted complication of the above.

The entire classification may be summarized as follows: