Table of Contents

One of the most frequently asked questions is: “Where is copper (price and usage) going?” I will not attempt to forecast either the future price of copper or the future growth of the copper industry; rather I would like to discuss the current trends experienced in the smelting and refining terms and conditions for sales and/or purchases of copper concentrates.

A brief review of contract language and terms, together with a review of the common jargon, I believe, would be helpful. To accomplish this review, I will first list what I consider the four basic parts or sections of a basic ore contract and then illustrate basic terms with calculations.

Most ore contracts contain or refer to items in the following basic outline:

A) 1. Contracting Parties

2. Product

3. Quality

4. Quantity

5. Duration

B) 1. Delivery Basis (F.O.B., C.&F., C.I.F., etc.)

2. Shipping Schedule

3. Constructive Delivery

C) 1. Metal Payments and/or Return of Metal

2. Treatment and Refining and Delivery Deductions

3. Penalty Items

D) 1. Weighing, Sampling and Assaying

2. Settlement

3. Force Majeure

4. Diversion

5. Arbitration

6. Definitions

7. Specific Issues: Environmental Situations, Economic Stabilization, Duties, etc.

Many of the above items are self-explanatory and need no further discussion; others I will comment upon and advise what ideas or attitudes reflect recent trends.

Part A

Contracting Parties is self-explanatory but in this changing world one often wonders if an erasable “player program” would be helpful. An item to consider is a succession clause or phrase outlining what the contracting parties are obliged to in case of sales, disbandment or merger of one or both contracting parties.

The elements and description in the Product and Quality clauses are continuously increasing. The advent of better analysis methods and equipment together with environmental concerns has made analysis in the parts per million (ppm) range common. Transportation of specific forms of product are also of great concern; many of our industry’s products are now “hazardous materials”, which require much documentation.

The Quantity of product is basic and important. If a seller is to split his product between two or more buyers and/or markets, he must decide if a “tonnage” or “per cent of production” basis best suits his needs and desires. The buyer, especially if he is a smelter and/or refiner, must also carefully consider the quantity to be received as he is “committing his smelting/refining capacity”.

In recent years, many variations of duration clauses have appeared. The fixed duration at fixed terms, i.e., one or two years duration is still the most common but the following variations are often seen:

a) Frame contracts. The parties of a frame contract will agree in principle that the seller will sell and the buyer will buy for fixed duration; for example, 3 years with the specification that the terms and/or tonnage will be negotiated (in good faith) each year for the next succeeding year. This is in essence an “agreement to agree”. It is advisable to fully understand what obligation each party is to commit to under a frame contract.

b) Multiyear-split tonnage contracts are agreements wherein the total tonnage is covered in two or more contracts—these contracts having consecutive terms of duration. For example, two contracts for one-half of the production each, with the duration of the contracts being for two years and four years. The main advantage or multiyear-split tonnage contracts is that the total production does not come up tor renegotiation at the same time.

Part B

- Delivery Basis clauses of ore contracts define at what point and under what conditions and terms the seller will make delivery and the buyer will accept receipt of the product. With “currently as produced” rail shipments the clause is usually straight forward. Large tonnage ocean-freighted shipments can become very involved and costly, especially when a clear understanding of each party’s obligations are not reached at the onset of negotiations. Acronyms and/or initials, such as C&F, CIF, CIF FO, etc. should be “spelled out” to eliminate later confusion.

- A Shipping Schedule is self-explanatory and very important when considering large ocean-going tonnages. A word to the wise—keep a shipping schedule as flexible as possible without losing definition—late or delayed shipments can be expensive.

- A Constructive Delivery or pricing schedule is incorporated into most large tonnage contracts, especially when ocean-freighting is involved. Basically, the clause restricts or defines the tonnage that will be considered as delivered or priced in any one time period. This provides for continuity in metal pricing especially for large ocean shipments.

Part C

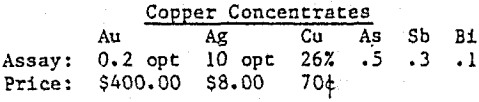

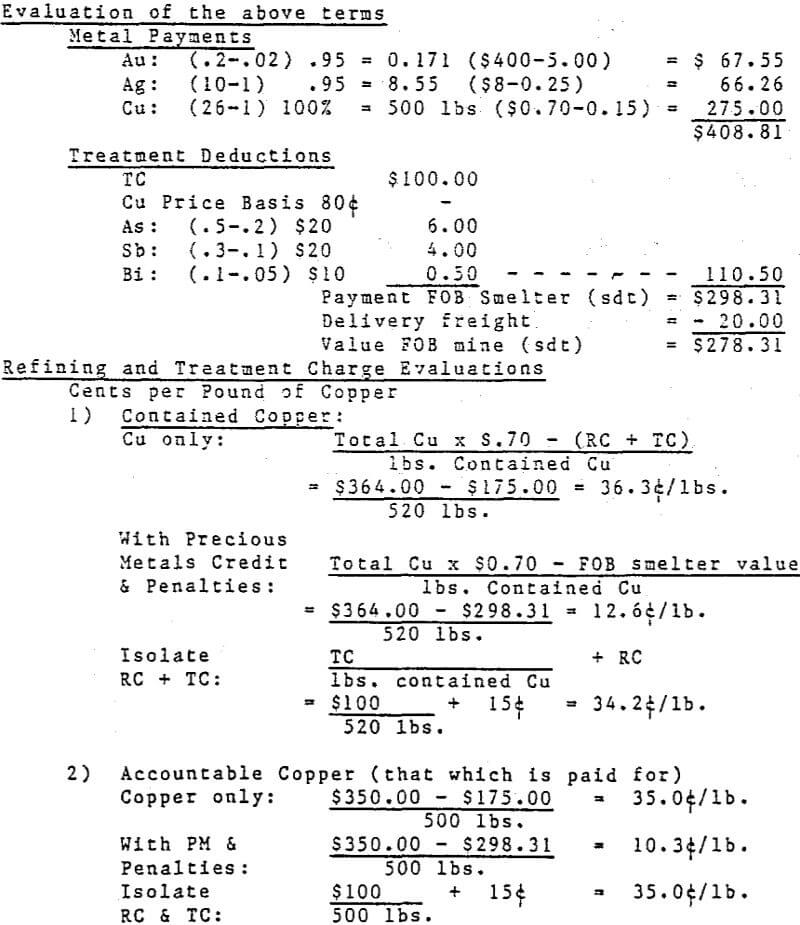

The Metal Payments, Treatment and Refining and Delivery Deduction, and Penalty Items of ore contracts perhaps can be best reviewed by first looking at a basic calculation of terms. For simplification, i have used abbreviated terms for copper concentrates having the following specifications and quotations:

Metal Payment

Gold: Deduct 0.02 Troy ounces per short dry ton (sdt) and pay for 95% of remaining gold at London final quotation less $5.00 per ounce.

Silver: Deduce 1.0 Troy ounces per sdt and pay for 95% of remaining silver at Comex 1st position quotation less 25¢ per Troy ounce.

Copper: Deduct 1 unit and pay for 100% of the remaining copper at Comex 1st position quotation less 15¢ per pound of copper.

Treatment Deduction

$100 per sdt of product Cu Price: Basis 80¢ per pound settlement quotation for copper, increase TC $1.00 for each the settlement quotation is greater than 80¢ per pound.

Penalties

As: 0.2 unit free, $20 for each 1 unit over 0.2 unit.

Sb: 0.1 unit free, $20 for each 1 unit over 0.1 unit.

Bi: 0.05 unit free, $10 for each 0.1 unit over 0.05 unit.

The Metal Payments, Treatment and Refining and Delivery Deductions, and Penalty Items (if any) are seldom as simple as the foregoing terms and calculations. As any seller will agree, any one concentrate offered to any four buyers will result in at least four different sets of terms and conditions. The broader the marketing base the more the variety.

The deductions from the total contained metal in the Metal Payment clause will vary from smelter to smelter and country to country but will usually reflect not only metallurgical consideration but also the supply-demand state of the market. The pricing basis will also vary from market to market. U.S. smelters usually base copper payment on either a Comex quotation or U.S. Producer Price. Recent trends are toward a Comex-based quotation. Canadian producers used a mixture of U.S., Canadian and London Metals Exchange (LME) based quotations, while the “World Market” uses the LME quotation.

The “quotational period” or the period during which the metal prices are established is usually stated in the metal payment clause. The quotational period may vary from calendar month prior to shipment to third or fourth calendar month following date of delivery. This, of course, impacts upon the timing at which payment is made as well as the level of price.

In the metal payment clause there is usually a deduction made from the metal price which is the Refining and Delivery Charge. These charges may be escalated In the same manner as the treatment charge.

The Treatment Charge is usually a fixed number which is then escalated on some basis. The basis can be actual labor, fuel and/or power cost increases, or indices such as CPI or GNP, or may be a fixed per cent of the base charge increased on a year-by-year basis. The current trend appears to be the latter two methods.

The Penalty Items of an ore contract are usually straight forward and will encompass all the elements which are deleterious to processing of the concentrate. Current trend is to include more penalty items due to both metallurgical and environmental restraints. Some elements may be restricted such as Hg, since no penalty will cover its impact.

Part D

These clauses are usually considered the administrative clauses and basically address how the concentrates are to be handled, how payment will be made, and how some possible differences are to be resolved. Of these clauses only the Settlement clause will be considered here since it usually is the only clause of the group which appears to change on a trending basis.

The Settlement clause basically addresses how and when the seller is paid for his product. As with most contract clauses, this clause has appeared in a variety of forms but usually contains provision for advance payment or provisional payment, interest charges, if any, date of final settlement, currency in which payments are to be made and, if necessary, appropriate exchange rate provisions. This clause like the clauses of Part C, Metal Payments and Treatment and Refining Charges respond to current market conditions.

Following this brief review of a simple ore contract, a quick review of the concentrate market of the past couple of years up to the present time may better explain some of the current trends in the market place.

With the closure of Anaconda’s Montana Smelter in 1980, the copper concentrate market appeared near in balance if not slightly over-supplied. Beginning in approximately mid-1981, various higher cost or marginal mines began to either close or curtail operations. This, combined with an increase of World smelting capacity, gradually moved the market for custom copper concentrates into short supply.

The tight market for custom copper concentrates, together with the uncertainty of the copper market, has brought changes to the “traditional” ore contracts. Another look at some of the items of a simple ore contract may be in order to examine the recent changes or trends of smelting and refining terms and conditions.

The Duration of more contracts are of shorter term; seldom does one see contracts of duration in excess of 5 or 7 years—most are in the range of 2 to 3 years. This, of course, is due to uncertainty of the market, the present supply unbalance of the market, and smelters unable to commit at such unremunerative terms.

The Delivery Basis of many current contracts has shifted from FOB smelter or CIF importing country to FOB mine of FOB vessel exporting country, all of which shifts the expense and obligation of freight to the buyer and many times also puts the obligation of the Shipping Schedule on the buyer.

Metal Payments, Treatment and Refining and Delivery Deduction, and Penalty Items are usually the first and most visible items to change. In the last year, much publicity has been concerned with the low levels of treatment charges and refining charges (TC/RC).

Quotational periods and Settlement clauses have also undergone various changes. These changes reflect not only the seller’s needs or ideas of “cash flow” or “time value of money” but may also allow the buyer an advantage by use of the market contango.

There are, of course, more items and concepts of ore contracts that trend with market change. The ones examined herein are the more common and visible and even their variations are far more than what has been discussed. The terms and conditions will change to provide a basis for the business that will be done.