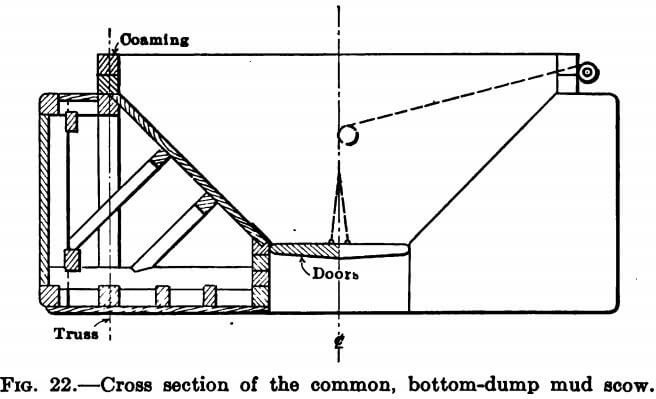

The most common conveyance for the transportation of dredgings (pumpings excepted) is the bottom-dump mud scow. It is in effect a hopper barge, without means of self propulsion, consisting simply of a hull rectangular in plan and cross section, containing a number of independent hoppers called pockets, and with both ends raked or rounded (in elevation) for towing in either direction. Roughly, it is somewhat more than three times as long as it is wide, and the depth of hull from deck to bottom planking is about one-third of the beam. When light, it has considerable freeboard, but when fully loaded, it floats with decks awash, the material being retained by the pocket “coamings”—a name given to the portions of the pocket walls projecting above the deck. The coaming height is usually from two to three feet.

The common form of cross section is shown in fig. 22. Neglecting the fore and after holds, between the ends of the scow and the faces of the first and last pockets, the vessel is dependent for buoyancy upon the polyhedral spaces between the sides of the scow and the sloping side walls of the pockets, unless the continuity of the pockets is broken by one or two transverse holds, as is sometimes done, not merely to increase the displacement, but also to add to the transverse strength. Thus, the displacement tonnage per inch immersion decreases quite rapidly as the draft increases, and the loaded scow has no reserve buoyancy. While these two features may appear objectionable, and while we do hear, occasionally of the capsizing of a mud scow, yet the good points of the design are so preponderant and the disaster of capsizing so trivial that the popularity of the type lives on.

It will be remembered that mud scows are loaded, not as the designer would have them for minimum stresses in the structure, but from one end to the other, and that usually they are dumped in the same way. Obviously the resultant tendency is to “hog” the scow, i. e. by negative bending moment in the structure as a whole, to render it convex upward. To provide adequate stiffness longitudinally, therefore, a pair of strong trusses are built in the plane of the side coamings for the full length and depth of the scow. In timber scows, they are generally of the Howe type. Supplementing them, the sides of the

vessel are detailed to further resist the “hogging” strains in that the upper strakes are in long lengths and spliced with long tension scarf joints. The lower strakes are as a rule framed with long scarf joints without the tension feature. The intermediate courses may be butted at stanchions. The truss rods should be provided with turn-buckles, that they may be adjusted to timber shrinkage and local fibre crushing. The transverse strength of the scow is provided by the walls between pockets, which are solid bulkheads extending the full width of the ship.

The floor of each pocket consists of a pair of doors, hinged at the sides to open downward at the centre. A chain at each end holds them horizontal or closed, running through a lead chock to a shaft just outside the coaming.

Upon this the chain is wound by lever bar, ratchet wheel and pawl. Each pocket has its own gear and is dumped independently of the others, by pounding the pawl out of engagement with the ratchet wheel, whereat the chain is released, the doors fall open and the load drops through. Although not always feasible, it is desirable that the depth of well below the door hinges be equal to the width of a single door, in order that the doors when open may not project below the bottom of the scow, in which position they are liable to damage in shoal water.

Whatever the material of which the scow is constructed, it should be strongly and durably designed, to withstand the severe treatment necessarily meted out to it. Although steel has been used in some instances, timber appears to be best adapted to the purpose and is quite prevalent. Current practice builds the body of the scow of long leaf yellow pine, of prime inspection, with corners and deck strake of white oak. The corners are armored with steel plates. The scow is always moored to the dredge with the shaft and winding gear on the side remote from the dredge, so that the danger of damage to the gear shall be reduced to a minimum. The coamings on the port side, therefore, are fitted with eye-bolts at each pocket to receive the hook of the breast line from the dredge. Consequently, it is the port coaming and the port side of the hull that wear most rapidly, due to the destructive impacts of the bucket. For this reason, the port side is not uncommonly sheathed with 2 or 3 inch oak or pine, preferably the former. Sometimes the two ends are protected likewise, and in teredo-infested waters, such sheathing on all sides is of paramount importance. The scow is equipped with towing bitts, and with hatches for ventilation and siphoning out fore and aft.

For river and harbor work, scows of 500 or 600 yards capacity are the most popular. Larger sizes present the objectionable features of great freeboard when light, requiring an inordinately high bucket lift, and great draft when loaded, requiring deep water for dumping. The latter becomes an important factor in dumping to a hydraulic machine for pumping ashore. In this instance, the so-called rehandling basin, or rectangular hole excavated by the pumps to receive the dumped material, is located preferably as close to the impounding basin as the consideration of minimum depth for dumping scows will permit, the idea being of course to reduce the length of discharge pipe line to a minimum. Hydraulic dredges engaged in rehandling work are required to maintain a depth in the rehandling basin at least as great as the surrounding depth, in order that as little material as possible shall be lost between dumping and pumping. The limits of the re¬handling basin are defined by ranges to control the operation.

Scows of types other than the bottom-dumps are in less common use for handling dredgings. For rock and commercial sand and gravel, deck lighters are employed. Particular attention must be given here to the design of the deck for the heavy loads and impacts. For rock, a layer of sheathing is usually laid on the deck planking. Concrete deck scows have been successfully used for sand and gravel. Deck lighters may be converted into mud scows by erecting on the deck a series of gable bottom bins, with the ridge in the plane of the longitudinal axis of the hull, and discharging through vertical doors on both sides. Such an arrangement is particularly adaptable to shoal water, although the centre of gravity of the loaded scow is abnormally high, and dumping at times proves a rather delicate operation. A second method of rigging deck scows to discharge their loads is by the use of a sliding deck platform mounted on rollers on a slight incline. This false deck when loaded and unlatched slides to one side by gravity for a distance of several feet, when it is checked by a stop. The momentum of the load and its eccentric position cause the scow to list until the material slides off into the water, whereupon, the scow, released, rights itself.

For towing to sea, large dump scows, upwards of 2000 yards capacity, have been used, and in some instances self-propelled hopper barges have been employed to transport dredgings.