The disposal of spent ore from cyanide heap-leach processing facilities is of concern to the mining industry, regulatory agencies, and the public. Disposal of several hundred million tons of additional spent ore is planned in the western United States during the next decade, with increased amounts likely if gold prices rise. In the past decade, more than fifteen million tons of spent ore have been disposed of in the Black Hills. South Dakota’s off-loading criterion for cyanide has been set by the state’s Department of Environment and Natural Resources at 0.5 parts per million (ppm) as weak acid dissociable (WAD) cyanide. Nitrate off-loading limits rary for each mine in the state, depending on ore type and other factors. Nitrate concentrations in leachate from spent ore depositories could be caused by conversion from other nitrogen-containing species.

Gold mines in the northern Black Hills of South Dakota normally use the following steps in their heap-leach cyanidation processing: blasting of ore with ANFO explosives, cyanide treatment of ore, collection of process solution for recovery of gold, neutralization of cyanides in spent ore, and disposal of spent ore in tailings facilities.

Surface gold mines in the Black Hills use ANFO explosives (approximately 95% ammonium nitrate and 5% fuel oil) to reduce rock to sizes small enough to be hauled to crushing equipment. Field evidence and studies-show that explosives often fail to ignite or burn completely in shot holes. Ammonium nitrate absorbs moisture readily, reducing blast efficiency.

At surface gold mines in the northern Black Hills, cyanide is irrigated in a dilute solution over the heap. Cyanidation is carried out at a pH of approximately 10.5 to minimize the formation of hydrogen cyanide gas.

Methods of destroying cyanides include hydrogen peroxide oxidation, natural degradation and evaporation, water leaching, alkaline chlorination, and sulfur dioxide oxidation. Hydrogen peroxide is used to neutralize cyanides in the northern Black Hills mining area. The hydrogen peroxide neutralization reaction forms cyanate, which can hydrolize to form ammonium and carbonate ions. After formation of ammonia or ammonium ion, further oxidation to nitrite (NO2-) and nitrate (NO3-) can occur.

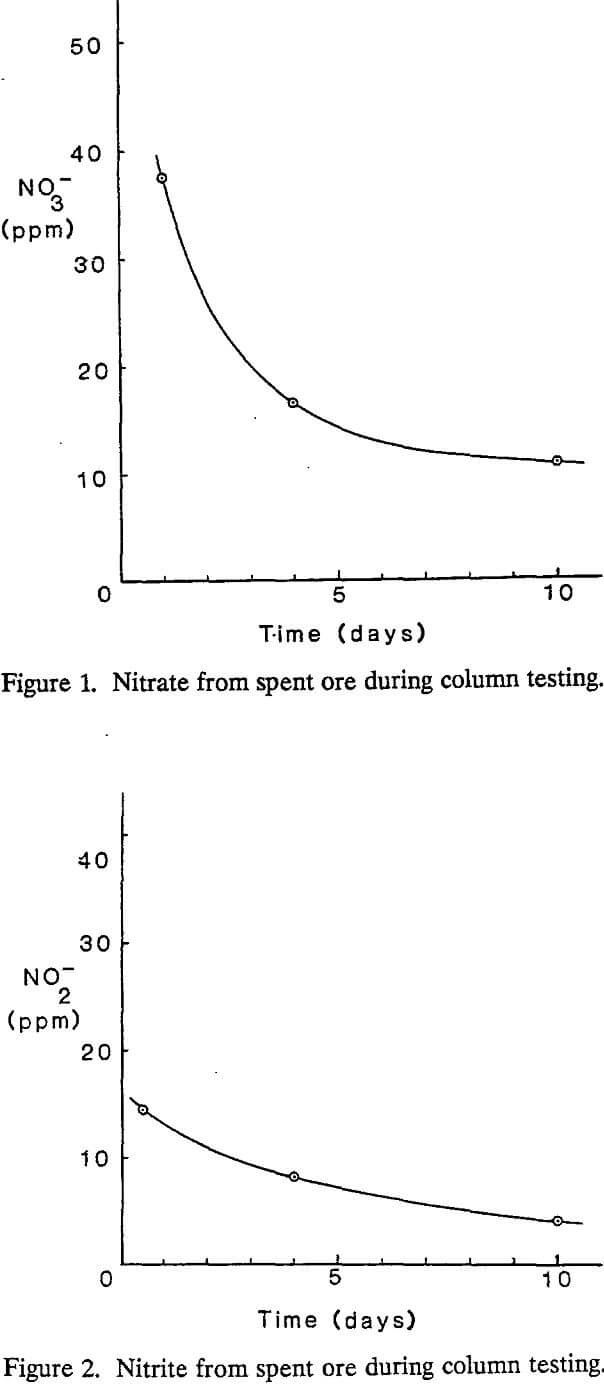

Blasted but untreated ore samples were collected and stored by mining company personnel. Collection of untreated samples was done with a paddle sampler that traversed a conveyor belt once for every 75 tons of material. Mining company personnel stored the blasted, untreated material in buckets and composited it at the end of each eight-hour shift.

Leaching tests were conducted with simulated rainwater that was prepared by exposing distilled water to the atmosphere until its pH stabilized at approximately 5.6, similar to rainwater in the northern Black Hills. An amount representative of one rainy season (approximately 25 centimeters of precipitation) was added to each column in ten equal amounts daily during a ten-day period.

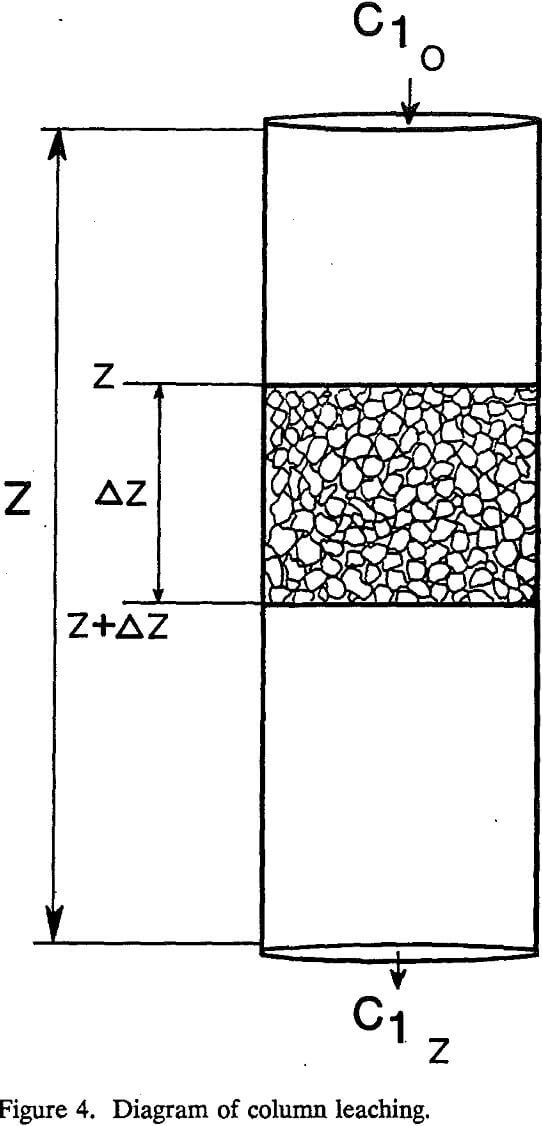

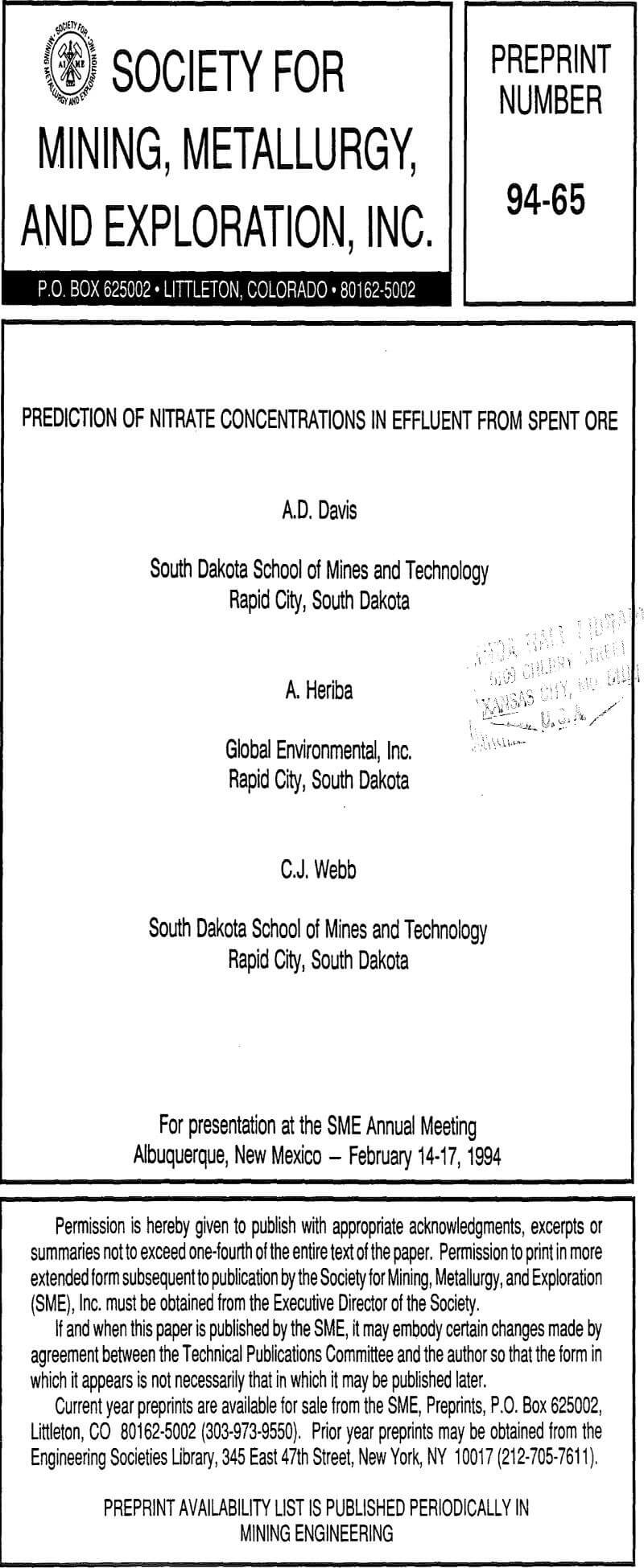

Nitrate and nitrite were easily observed during column testing with spent ore. Levels of both contaminants decreased monotonically as a function of time.

The levels of nitrate and nitrite in spent ore were significantly less than those observed in the previous study and showed only a slight contribution from conversion of nitrite to nitrate. This is attributed to reported changes in the total levels of nitrogen introduced into the processing stream, both by a reduction in use of cyanide and a more efficient blasting procedure.

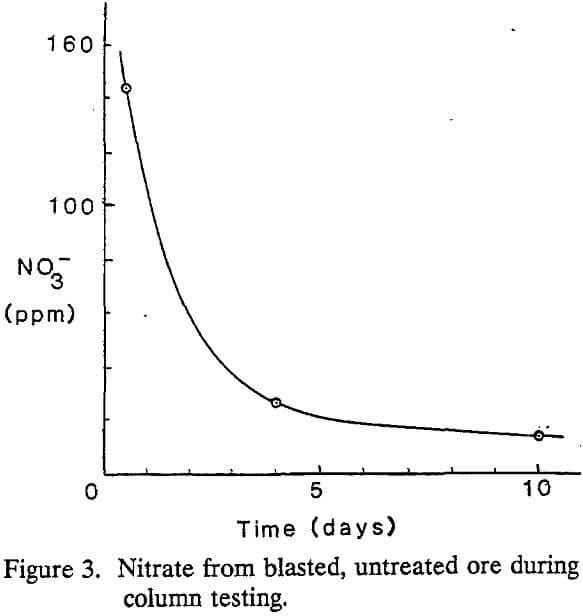

Mass-transfer calculations are useful because column tests and bottle extractions take only a short time to run and provide useful data for predictions. Mass transfer in column leaching include solubility, advection, mechanical dispersion in the porous medium, and diffusion.