The accuracy of the silver-assay depends in great measure upon a careful regulation of the heat of the muffle furnace during the process of cupellation. At the beginning of the operation, a relatively high temperature is required to ” open ” the lead buttons, that is, to clear off the black film of oxide that covers the surface of the metal button immediately after fusion has taken place. The muffle furnace is usually closed up until the buttons are uncovered. As soon as a clear, free surface of molten metal is exposed to the oxidizing action of the air, the temperature should immediately be lowered to the minimum temperature at which the formation and absorption of litharge can progress freely, and the buttons still be kept from ” freezing.” The process, under satisfactory conditions, will be characterized by the formation of rings of litharge crystals (” feathers,” as they are styled), on the cupel, about the oxidizing globule; and the nearer these rings of litharge crystals can be made to approach the central oxidizing globule without interfering with the freedom of oxidation and absorption, the smaller will be the volatilization of silver, and consequently the greater the degree of accuracy attained. This minimum heat must be maintained uniformly during the oxidation of the lead; and just as the last of the lead is disappearing, and the button is preparing to ” blick,” the temperature of the muffle furnace should be allowed to rise so that the last traces of lead will be driven off. This regulation of the heat calls into play all the skill of the assayer, and requires a vigilant eye, able to distinguish between the slightest variations of temperature of the muffle, assisted by a nice adjustment of fuel and draft. With a few cupels in the muffle furnace at one time, the proper heat for each cupel can be maintained by roughly approximating the proper temperature, and then moving the cupels backward and forward in the muffle furnace; but this is generally out of the question where hundreds of determinations must be made in a day, and therefore some other method of regulation must be employed. With this end in view, the skill of the assayer will show itself in securing a nearly uniform size of lead button from the preliminary scorification or crucible fusion, so that, when handled in one batch, the buttons will finish cupelling at nearly the same time. The problem then is to lower the temperature of the whole muffle furnace suddenly and uniformly, after the buttons have opened, keep it steady during the cupellation at the minimum temperature, and then suddenly raise it at the end, to secure a ” hot blick.” The solution is to be found in keeping the fire hotter than is necessary to hold the muffle furnace at the proper degree and cooling the latter by independent agencies, which can be regulated with greater nicety than can the fire itself, and which, when removed, permit the surplus heat of the fire to assert itself, and quickly raise the temperature of the muffle. Ordinarily this is done by placing cold bodies, such as old crucibles and scorifiers, in various positions in the muffle furnace, where they will have the cooling influences desired, even going to the extent of putting here and there, in actual contact with the cupels, a cold scorifier, resting on the raised edges of two or more cupels, so as not to cut off the supply of air. In the hands of a skillful assayer a muffle full of cupels can be manipulated as perfectly as a single row, with every button surrounded with a ring of beautiful litharge feathers.

The accuracy of the silver-assay depends in great measure upon a careful regulation of the heat of the muffle furnace during the process of cupellation. At the beginning of the operation, a relatively high temperature is required to ” open ” the lead buttons, that is, to clear off the black film of oxide that covers the surface of the metal button immediately after fusion has taken place. The muffle furnace is usually closed up until the buttons are uncovered. As soon as a clear, free surface of molten metal is exposed to the oxidizing action of the air, the temperature should immediately be lowered to the minimum temperature at which the formation and absorption of litharge can progress freely, and the buttons still be kept from ” freezing.” The process, under satisfactory conditions, will be characterized by the formation of rings of litharge crystals (” feathers,” as they are styled), on the cupel, about the oxidizing globule; and the nearer these rings of litharge crystals can be made to approach the central oxidizing globule without interfering with the freedom of oxidation and absorption, the smaller will be the volatilization of silver, and consequently the greater the degree of accuracy attained. This minimum heat must be maintained uniformly during the oxidation of the lead; and just as the last of the lead is disappearing, and the button is preparing to ” blick,” the temperature of the muffle furnace should be allowed to rise so that the last traces of lead will be driven off. This regulation of the heat calls into play all the skill of the assayer, and requires a vigilant eye, able to distinguish between the slightest variations of temperature of the muffle, assisted by a nice adjustment of fuel and draft. With a few cupels in the muffle furnace at one time, the proper heat for each cupel can be maintained by roughly approximating the proper temperature, and then moving the cupels backward and forward in the muffle furnace; but this is generally out of the question where hundreds of determinations must be made in a day, and therefore some other method of regulation must be employed. With this end in view, the skill of the assayer will show itself in securing a nearly uniform size of lead button from the preliminary scorification or crucible fusion, so that, when handled in one batch, the buttons will finish cupelling at nearly the same time. The problem then is to lower the temperature of the whole muffle furnace suddenly and uniformly, after the buttons have opened, keep it steady during the cupellation at the minimum temperature, and then suddenly raise it at the end, to secure a ” hot blick.” The solution is to be found in keeping the fire hotter than is necessary to hold the muffle furnace at the proper degree and cooling the latter by independent agencies, which can be regulated with greater nicety than can the fire itself, and which, when removed, permit the surplus heat of the fire to assert itself, and quickly raise the temperature of the muffle. Ordinarily this is done by placing cold bodies, such as old crucibles and scorifiers, in various positions in the muffle furnace, where they will have the cooling influences desired, even going to the extent of putting here and there, in actual contact with the cupels, a cold scorifier, resting on the raised edges of two or more cupels, so as not to cut off the supply of air. In the hands of a skillful assayer a muffle full of cupels can be manipulated as perfectly as a single row, with every button surrounded with a ring of beautiful litharge feathers.

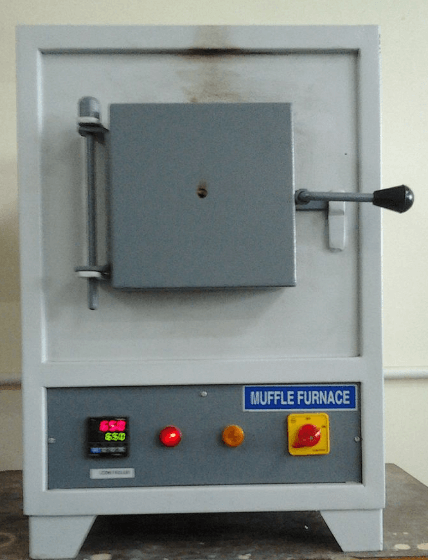

It is the object of this paper to call attention to an improvement upon this method of temperature-regulation, which has been in use for over a year in the assay-department of the Colorado Smelting Company, at Pueblo, and which was devised by Mr. Howard F. Wierum, the assayer in charge, with the co-operation of Mr. F. L. Capers, President of the Standard Fire Brick Company, of Pueblo, who has shown much intelligence and skill in carrying out the idea. The muffle is moulded with two sets of horizontal ribs on the inner sides, running from front to back. These strengthen the muffle, and at the same time serve to support a loose slab of burned fire-clay about ½-inch thick, with the same width as the muffle, which can be slipped in like a shelf. It was originally hoped to cupel successfully several stories of cupels at the same time, but this is not practicable.

Used simply as a means of heat-regulation, however, the effectiveness of this arrangement is remarkable, and most perfect results in cupellation can be obtained with its aid. When the shelf is slipped over a batch of hot buttons that have just opened, a shade passes over the muffle uniformly, as the temperature suddenly falls. By replacing the heated slabs with cooler ones, the temperature can be kept steady; or if certain rows of cupels are too hot, short strips of slab can be placed exactly over the spots desired. The risk of getting the temperature so low as to ” freeze ” the buttons can be avoided by placing dummies, or indicators in the front rank of cupels, where the temperature is lowest. When these show signs of freezing, it is an indication that the temperature is getting too low, and proper steps must be taken at once to correct it. By then removing the shelves entirely, the temperature will rise rapidly, if the fire is in proper condition. “ The Cathedral Muffle Furnace” is the name given to this design, from its fancied resemblance, when in operation, to the interior of an illuminated church.