Table of Contents

In the West, capitalists have expended many millions of dollars developing the low-grade porphyry ores of copper. Half a dozen of these great enterprises have proved to be wonderful commercial successes. They have demanded improved crushing and concentrating machinery and consequently it has been developed. Many improved methods, cheap power, superior business organization, all these have contributed to this success, but the main feature is the handling of the material in enormous quantities, on a manufacturing scale. The mining chance of “striking it rich” has been eliminated by the manufacturing certainty of handling large quantities of material of known value, which while of relatively low grade, is available in large tonnages, assuring a supply for many years’ run of the mill. Then the returns on the money invested are sure.

The concentration of low-grade magnetic iron ores, separating the magnetite crystals from the gangue by the use of magnets, is a field of work in which the lessons taught by the development of the porphyry coppers can be studied to advantage. Large-scale operations, and the liberal expenditure of enough money at the start to insure the most economical operations, are the means of securing the desired results.

The problem is to utilize millions of tons, and we may safely say billions of tons, of now worthless iron-bearing rock and to produce from it 10,000,000 to 20,000,000 tons per year of high-grade ore carrying 60 per cent, iron or higher; to take the lean material as found in nature, varying widely in iron content, and bring it up to a uniform standard of shipping ore. At present these ores are mined carrying from 25 to 50 per cent, iron, and the shipping product is brought up to 60 or 65 per cent. Fe. If future economies of operation make it possible to extend this process so that 15 per cent, iron in the crude ore can be treated as a commercial success, the additional tonnage available will be enormous. A 15 per cent. Fe crude ore raised to 60 per cent. Fe concentrate with 5 per cent.

Fe loss in tailings would require 5.5 tons of crude for 1 ton of concentrates. The cost of crushing and concentration can be brought down to 12 c. per ton crude or possibly to 10 c., and the cost of quarrying on a large scale, probably 40 c., would be low enough to leave a profit even now. There are mountains of gabbro rock in the Adirondacks that will average 15 per cent, iron in the form of magnetite crystals of good size, say 1/8 to 1/16 in., but the concentrate would also carry some titanium.

Magnetic Iron Ore Resources

A thorough examination of some of the iron-ore properties and the knowledge acquired by development of extensive underground workings makes it possible to make quite definite estimates of tonnage available in certain areas, which show very large reserves.

F. S. Witherbee in his paper read before the American Iron and Steel Institute last October gave an estimate of 1,100,000,000 tons of crude magnetic ore above 30 per cent. Fe available for concentration in the Adirondack region alone, not including any titaniferous ores except the one deposit at Lake Sanford. He practically confined his estimate to the area of the iron-bearing gneisses which surround the central core of later eruptives, the anorthosites and gabbros, in which the titaniferous ores are found.

There are also in New Jersey and southeastern New York large areas that give conclusive evidence of vast amounts of non-titaniferous magnetites. The map accompanying the report of the State Geologist of New Jersey, year 1910, shows the area of iron-bearing gneiss rocks running northeast and southwest across the State about 18 miles wide by 50 miles long, from Phillipsburgh to Greenwood Lake. In this area are located by name 366 magnetite mines that have been worked more or less. There are also 24 limonite and 8 hematite mines. These lenses may easily be capable of producing an average of 1,000,000 tons each and there are probably double the number listed not opened up. Here we have 900 sq. miles of iron-bearing gneisses in New Jersey, or more than in the Adirondack region, with nearly as much more additional in southeastern New York, reaching from the New Jersey line across the Hudson at Fort Montgomery and extending to Brewsters.

Mr. Witherbee’s method of computation estimated 20 ft. thickness of ore over 10 per cent, of the surface area. He afterward cut the estimate, in half to be conservative, which was equivalent to 10 ft. thickness of ore on one-tenth of the surface. This would give 2,700,000 tons per square mile or on 900 sq. miles in New Jersey 2,300,000,000 tons, with a goodly area in New York to-fall back on to make up deficiencies.

A recent examination of a small area of 4 sq. miles near Sterling and Tuxedo Lakes in New York near the New Jersey line, showed ore reserves estimated at 5,000,000 tons per square mile.

Magnetic ore is found quite widely distributed, in Canada, Minnesota, California; New Mexico, New York. New Jersey, Pennsylvania, North and South Carolina, Tennessee. A detailed study of these deposits might be an interesting subject for the Bureau of Mines to follow up.

History of Development of Magnetic Separator

Some time in the, year 1887 my attention was called to the magnetic separation of ores. At that time Edison was experimenting with his deflecting magnet and the Wenstrom, a Swedish machine of the drum type, was in use. The Conkling machine, which was also on the market, was the forerunner of the modern belt machine, but the magnetic attraction came from a single magnetized plate.

My first experiment was with Port Henry old-bed ore, which I crushed to pass through 1/8 in. mesh, and then ran through an old-fashioned fanning-mill, such as are used on farms. I had better results than those obtained by Mr. Edison with his deflecting magnet. I then made a trial of the Conkling idea but found that the magnetic plate picked up a large part of the gangue with the ore, so that the ore had to be sized and fed very slowly to get good results. The same trouble was experienced with the Wenstrom machine.

I then made a small machine, substituting common horseshoe magnets , for the magnetic plate of the Conkling machine. Since the magnets were of north and south polarity the ore turned end for end in moving from one pole to the next—not only the loops of ore and gangue but each individual piece turning. In this way the gangue was allowed to drop out, the ore was held, passed on to the next magnet, and so finally cleaned of the non-magnetic rock.

This use of magnets of alternating polarity is the fundamental principle of the Ball-Norton separator and greatly increases the capacity and efficiency of the machine.

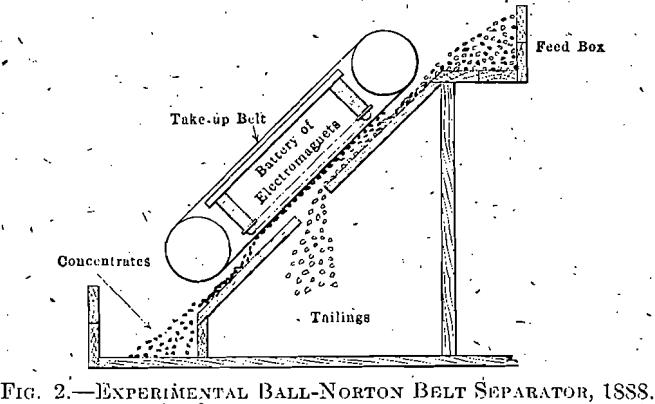

However, as I was not an electrical engineer, I went to a friend, Clinton M. Ball, explained the operation of the machine, and told him that if he would make electromagnets of sufficient size and power, of alternating poles, I thought they would be a great improvement over anything previously used. Mr. Ball made the magnets, a small machine was built (shown in Fig. 2), and taken to the Benson mines, where about

1,000 tons of 63 per cent. Fe ore was made, shipped to Braddock furnace and used there by James Gayley. This, I think, was the first use of magnetic iron-ore concentrates in a blast furnace.

The small machine was of the belt type. Mr. Ball soon after designed a drum-type machine, and later a double-drum machine in which a three-part separation was made. There are now magnetic machines of many types, but the majority use the alternating pole magnets.

Until 1908, I thought I was the first to use this form of magnet, but I then found that Z. Palmer had used the idea at Palmer Hill in 1854, so that it was not a new idea after all.

Mr. Palmer’s machine is an interesting example of an early crude use of an important scientific principle. It was simple and primitive in the extreme, consisting primarily, of a row of horseshoe magnets spiked around a log, like the spokes of a wheel. Finely crushed crude ore was allowed to slide through a wooden trough underneath the magnets, which were rotated by a crank attached to their supporting log. As the magnets rotated, they dipped into the trough, the good ore became attached to them and was lifted up. It was then transferred to another trough, set above, by employing the simple device of a broom wielded by a husky Irishman.

The number of so-called magnetic separators for which patents have been taken out has been so large that it would be a waste of time even to try to enumerate, them. Many of them were mere toys and a number were mechanical monstrosities. The belt and drum machines of the Ball and Norton patent have accounted for 90 per cent, of magnetic concentration by the dry process; while the wet magnetic process has been entirely monopolized in this country by the Grondal-type machine. There are no patents today controlling magnetic separation, and there is no longer any chance for any now or startling discoveries in this line.

The first magnetic separator that I constructed was of the belt type. It was operated with a feed belt running 125 ft. per minute, while the take-off belt ran 250 ft. per minute. I wished to make a careful test of the capabilities of the machine when working on an ideal material, so I prepared a special mixture for the purpose. This consisted of crushed white marble, washed and sized between 1/8 and 1/20-in. mesh; mixed with iron ore of the same size in a proportion of 2 parts marble to 1 part iron. It was evident that the particles of iron ore and marble would not be attached to each other, since the, mixture was purely artificial. This mixture was then fed to the machine in a stream ¼ in. deep. The separation was almost perfect, giving an iron product over 99 per cent. pure. In this way, the possibility of a complete separation was conclusively demonstrated. In actual practice, however, such thorough preparation of material is impossible, and, owing to the difficulty of properly preparing the ore, there are some cases where separation cannot be made a commercial success.

Treatment Method Determination

The magnetic iron ores found in different localities vary widely, not only in their iron content, but also in their physical structure. The ores from the various districts require, consequently, radically different treatment.

In the first place, bodies of ore differ widely in crystallography. For example, the ores of the Champlain Valley are more coarsely crystalline than the ores of New Jersey, the Benson mine, or the Cornwall ore bed. Obviously the mill treatment of these ores cannot be the same. Among other things, ore containing the coarser crystals would not require to be crushed to so fine a size as ore of the Cornwall type. It is very important to find the exact size at which any particular ore is most economically separated, and this size can easily be determined by experimental tests in a suitable laboratory. Moreover, the degree of fineness to which the ore must be crushed determines the process of separation to be employed. An ore which must be crushed to 1/8 in., 1/16 in., or lower will require the wet method of separation, while for larger sizes the dry method can be most profitably employed. The exact size that determines the method to be used is also somewhat dependent on the amount of moisture contained. Quite fine sizes can be separated if perfectly dry and fed in a thin film, but the dust problem is then somewhat difficult to deal with.

Present Practice and State of Development

The largest development in the iron-ore industry, using magnetic concentration, is at the plants of Witherbee, Sherman & Co. at Mineville, N. Y., where about 1,200,000 tons of crude ore were mined and separated in 1916. The dry process of separation is used. The Chateangay; Ore & Iron Co., at Lyon Mountain, N. Y., the Empire Steel &

Iron Co. and the Ringwood Co. in New Jersey, also use the dry process successfully. The Grondal wet separators have been recently installed at the Benson mines in New York. The largest development of the, wet process in this country is on the Cornwall ore at Lebanon, Pa. This work is in charge of B. E. McKechnie, who is the highest authority on the wet process.

In the practical application of magnetic separation the most vital part is the preparation of the ore. It must be crushed so that the crystals of magnetite, or groups of crystals, are sufficiently freed from rock to bring the percentage of iron up to the standard set for shipping ore. On the other hand, it must not be crushed too fine, if it is possible to avoid it, otherwise the blast does not pass through readily in the furnace, or the ore blows over the top.

To maintain the best possible physical structure the separation must be made at each stage of the crushing.

If the material going to the separators is sized, the strength of the magnets, can be adjusted to pick up the ore of more nearly uniform quality, but a separation can be made without very close sizing.

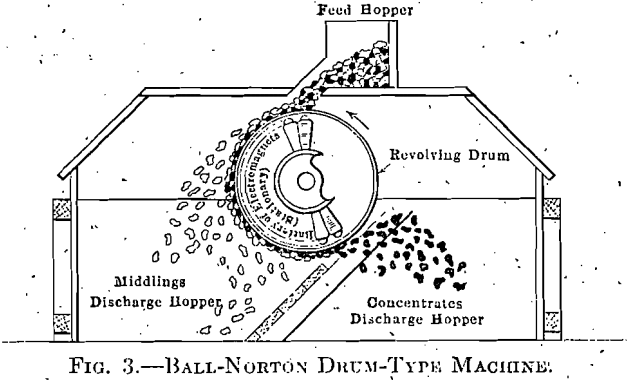

The drum type of machine (Fig. 3) has a section, of fixed magnets inside of a revolving drum. It is used on the larger sizes where the richer

ores can be treated as coarse as 1½ in. and a considerable percentage recovered. This size is as large as is desirable for rapid working in the furnace.

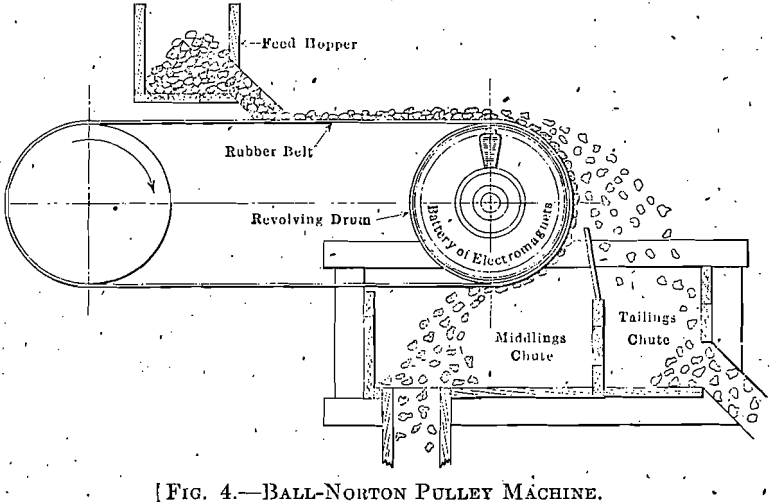

The pulley-type machine (Fig. 4) has a full circle of magnets which revolve with the drum. The magnets are wound to carry more-current than the-drum machine and will attract any lean ore, throwing off pure rock or tailings.

The drum and pulley machines will handle 30 to 50 tons per hour and are used together. The drum picks out any ore, as heads, rich enough for shipment. The pulley throws out rock lean enough to discard; what

is left as middlings is crushed to about half its size and passed to machines treating finer sizes.

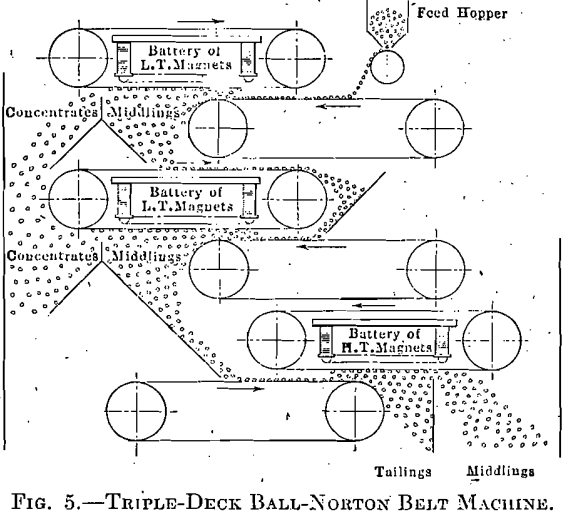

The belt-type machine (Fig. 5) is used when the ore is reduced to ¼-in. or below. The magnets are open to the air, so keep comparatively cool and are easily inspected. Since the magnets of the belt machine

lift the ore from the feed belt, the gangue is less likely to be held in suspension and a cleaner concentrate is insured. In the triple-deck machine shown in Fig. 5 the two top machines make heads and the bottom one makes tailings, and middlings to be reground.

All these machines are used in the dry process.

If fine grinding is necessary to separate the crystals of magnetite from the gangue, wet separation is indicated. In this case treatment by sintering, or other processes, to agglomerate the ore is also required. The sintering process solves another difficulty by removing sulphur. Low iron and high sulphur content are handicaps which can now be both overcome by the combination of magnetic concentration and sintering.

The accompanying flow sheets of mill No. 3 (Fig. 6), mill No. 4 (Fig. 7), and mill No. 5 (Fig. 8), of Witherbee, Sherman & Co. at Mineville, N. Y., show arrangements for treating, three different ores. The richness of the ore determines at what size the first separation can be made.

Mill No. 4 has eight sets of rolls instead of six in the other mills, because the ore is leaner and requires finer grinding.

Wet Magnetic Separation of Cornwall Ore

During the dry magnetic separating tests on Cornwall ore, it became evident that this process of magnetic separation was not suitable for this ore, for the following reasons:

Dust

The ore must be very dry in order to secure freedom of motion between the particles, or poor separation will result. This condition allows the very fine particles to escape as dust. No system of fans or other arrangements for eliminating or controlling this dust has been developed which can be successfully operated at a cost not prohibitive on this ore.

Low Grade of Concentrates

Owing to the tendency of the fine particles of talcy gangue to cling to the magnetic pieces, it was found impossible to raise the iron constant above 52 per cent, when separating the average grade of Cornwall ore. This fact is demonstrated by washing concentrates from the dry magnetic separation, when the iron content was easily raised from 52 to 58 per cent. This suggested using a combined process of dry magnetic separation and of washing the magnetic product in some such apparatus as the Dorr classifier.

The objections to this arrangement are:

- Dust problem is not solved.

- The combination of a dry and wet process has the disadvantage of both cost of drying and the cost of pumping water supply and handling of wet products.

The same or better results could probably be obtained by a wet magnetic separation. This process would eliminate the cost of drying, the dust problem and should give a higher recovery of iron, due to the fact that a certain amount of iron would be lost in the slime from washing of dry concentrates. In the wet magnetic separation this washing is carried out in a strong magnetic field, which greatly reduces the loss from this cause.

In connection with the results obtained from the experimental wet magnetic separator constructed for investigating the wet process of magnetic separation of Cornwall ore, attention is called to the following points:

It is evident that in the separation of any ore by magnetic or other forces, the ore must be crushed sufficiently fine to free the valuable minerals from the gangue, and also that the degree of fineness required in the crushing depends upon the physical characteristics of the ore. As it is impractical to carry the crushing far enough to free all the mineral from the gangue, there will be a certain percentage of attached particles or “middlings” consisting of both mineral and gangue.

In the case of magnetic separation, these attached particles may go either as concentrates or tailings, depending on the strength of the magnetic field and the ratio by weight of magnetic to non-magnetic material in each. From this it follows that the stronger the magnetic field, the lower in iron will be both the concentrates and tailings product, due to a larger quantity of attached particles being attracted to the magnets. The reverse also holds true, that, the lower the current, the higher in iron will be both the concentrates and tailings as fewer attached particles will go to the concentrates and more to the tailings.

The richer the crude ore, the higher will be the grade of concentrates and the higher will be the iron content in the tailings. This is due to the fact that the rich ore carries a greater proportion of rich particles and a smaller proportion of rock. The grade of concentrates is raised, due to the smaller percentage of attached particles, while the percentage of iron in the tailings is greater, because of the smaller amount of clean rock present to balance the small quantity of magnetic material entering the tailings.

Assuming that the amount of magnetic particles dropped by the separator is a nearly constant quantity, a higher percentage of recovery of iron is obtainable from a rich ore than from a leaner ore as the percentage of iron lost is evidently less.

The wet magnetic separator constructed for these experiments is a drum-type machine, constructed on the Ball-Norton principle. It consists of a number of stationary electromagnets, of alternate positive and negative polarity attached radially to a central shaft. About these magnets revolves a non-magnetic, water-tight drum, which carries a thin rubber belt.

In practice the magnets do not extend the entire circumference of the machine, but a gap is left between the points of feeding and delivery of concentrates. In this machine which was built for experimental work, any desired number of magnets could be cut out by short-circuiting the current around them.

Six arrangements of the drum were experimented with. Of these only Arrangement 1 was successful.

Arrangement 1.—The revolving drum drives the thin rubber belt which covers the face of the drum and passes over pulleys. Ore and water, or “pulp,” are fed by a launder or feed sole in such a manner that the feed is thrown against the moving belt. The magnetic particles are held to the drum, while the non-magnetic material falls into the tank and is drawn off. As the magnetic material held against the belt passes through the water, the influence of the alternating polarity of the magnets is to cause the magnetic particles to take a rolling action, which allows any entrapped gangue to fall out. As the drum further revolves, the magnetic concentrates are lifted out of the water and carried up the belt and around the pulley, where they are washed off by a spray of water.

In practice on Cornwall ore, it was found that a certain amount of very fine gangue was carried by the water into concentrates. They were, therefore, led to a classifier consisting of an inverted pyramid or tank, the bottom of which was fitted with a small hole and a connection above this hole for supplying clean water under slightly greater head than the depth of water in the tank. This water supply was regulated to furnish all the water required to supply the hole or the “spigot” and to furnish a slight raising current against which the heavy magnetic particles would fall but the very fine gangue could not, but would escape over the edge with surplus water.

Arrangement 2 was similar to 1 except that the water level in the tank was lowered until it was below the drum. This was done in an effort to reduce the amount of dirty water carried over the concentrates. The separator failed to make a separation operated in this manner, due to the fact that the surface tension of the water on the drum caused this water to act as a blanket, which did not allow the non-magnetic material to fall out.

In arrangements 3 and 4, the motion of the drum was reversed and the idler pulley removed. The feed sole was placed above to feed the pulp in the direction of travel of the belt. The tailings were to be removed at the tank and the concentrates, carried past the division board placed under the last magnet were to be removed by the spray of water. Due to the surface tension of the water, no separation took place above the water level. The separation accomplished beyond this point was destroyed by currents set up in the water by the rotation of the drum.

Arrangements 5 and 6 were similar to 3 and 4 except that the belt was removed and the material fed directly on the drum. The action was the same as in 3 and 4.

Following are results obtained from Arrangement 1.

Test No. 1.—This was a preliminary run to test arrangement of separator. The crude ore was a mixture of concentrates and tailings from a dry separation.

A series of determinations showed the iron in these tailings distributed approximately as follows:

4.24 per cent, combined with sulphur.

4.76 per cent, combined as silicates.

2.90 per cent, combined as magnetite.

It should be noted that 9 per cent, represents non-magnetic iron, or that about 75 per cent, of the iron occurring in this tailings sample is non-magnetic and cannot be charged to the inefficiency of the separation.

Concentrates were again separated with a lower current of 10 amp.

Concentrates………..56.60per cent, total Fe, 54.23 percent. Fe as magnetite.

Tails………………….28.95 per cent, total Fe, 20.49 per cent. Fe as magnetite.

The tailings from this separation are really a middling product consisting of attached particles.

Note high tails due to large amount of iron combined with sulphur.

Note that in using lower currents the iron content of the tailings increases more rapidly than in the concentrates.

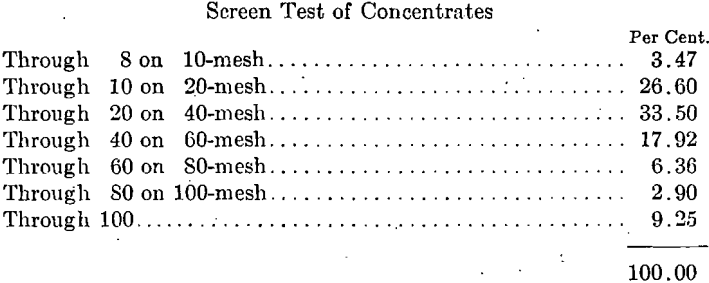

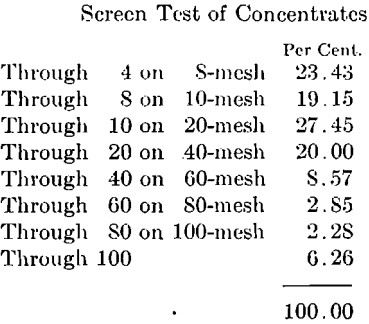

A screen test on the crude ore sample above and on the concentrates from the separation with 12.75 amp. gave the results shown in Table 1.

Note low grade of the coarse sizes of concentrates and that iron content does not reach 60 per cent, until 100-mesh size is reached. This shows the necessity for fine crushing.

Concentrates upon which the preceding screen tests were made were reseparated with 12 amp.

Concentrates……………57.90 per cent, total Fe, 56.55 per cent, magnetic Fe.

A screen test on this sample follows:

Note that the greatest gain in Fe content is in the fine sizes, due to washing out of fine gangue.

Crude……………………..38.30 per cent, total Fe, 33.64 per cent. Fe as magnetite.

Concentrates…………..58.40 per cent, total Fe, 55.97 per cent. Fe as magnetite.

Tails………………………10.20 per cent, total Fe, 2.17 per cent. Fe as magnetite.

Results of Dry Separation in Testing Laboratory

The following reports show results of samples tested to determine treatment required and quality of concentrates that could be expected. These tests were run on a regular mill size separator and the results could be duplicated in actual practice. The separate determinations of iron as magnetite, and total iron, were made so that the difference between the two would show the amount of iron combined as silicates in hornblende and other gangue minerals.

No. 234, Separation Test on Jackson Hill Ore, Arnold, N. Y.

307 lb. crude ore was crushed to pass 1/8-in. screen; separated, by screening, into two sizes, on 16 and through 16-mesh.

Through 8 on 16-mesh 132 lb., through 16, 175 lb.

8-16 size, treated on belt machine using 3½, 4, 5 amp. and finally with 4 amp. for heads. Then 12 amp. for midds and tails.

Crude 132 lb………………………………………

Heads 20½……………………………………Fe 63.35, P 0.006.

Midds 42½…………………………………………..Fe 25.10.

Tails 62…………………………………………………Fe 3.80

The midds were rolled through 16-mesh and added to crude through 16; the whole passed over belt machine using 2 amp.

Crude 224½ lb………………………………………Fe

Heads 115…………………………………………….Fe 66.15, P 0.005

Tails 108½………………………………………….Fe 3.00

General crude 307 lb……………………………….Fe 30.85 P 0.008

General cone. 135½…………………………………Fe 65.60, P 0.005

General tails 171½……………………………………..Fe 3.27

Ratio, 2.265 tons crude to 1 ton concentrates

Note.—Owing to the iron being present in very small crystals it is necessary to crush this ore to at least 1/8-in before separation, but since the ore is extremely brittle this is easily accomplished with little power.

The tailings consists almost wholly of red feldspar which could be utilized for potash extraction by the Cushman process which is now commercially successful.

The above heads being too low in iron, were added to midds and rolled through 8-mesh, fines screened out and added to crude.

8 on 16 size, passed over belt machine on 5 amp. for heads and 15 amp. for midds and tails.

The midds ground through 16-mesh, added to crude and passed over belt machine on 8 amp.

Crude 250½ lb.

Heads 146½…………………………………………..Fe 65.30, P 0.006

Tails 104……………………………………………………..Fe 8.65,

General crude 325 lb…………………………………………Fe 39.00, P 0.018

General conc. 177½…………………………………………..Fe 64.50, P 0.006

General tails 147½………………………………………………..Fe 8.05

Ratio, 1.83 tons crude per ton of concentrates.

Note.—In order to reduce the iron in the tailings finer grinding through 16-mesh will be necessary at the last stage making a three-part separation on the through 16 size and retreating resulting midds.

The midds were rolled through 8-mesh, screened and added to crudes. 8 on 16, 48 lb.; through 16, 26 lb.

8-16 size, passed over belt machine on 4 amp. and 15 amp.

The midds ground through 16-mesh and added to crude. Through 16-mesh, over belt on 7 amp.

The demonstration of the dry process of magnetic separation is the result of 14 years’ work at Mineville, N. Y. Witherbee, Sherman & Co. have now in operation three mills having a combined capacity of 6,000 tons per day of crude ore. The Empire Steel & Iron Co. and the Ringwood Co. have demonstrated what can be done with New Jersey ores. The Ringwood Co. has also worked out a dry process of jigging for their tailings to recover the martite, which is non-magnetic. Martite is a hematite in composition, but is very similar in appearance and crystallization to the magnetite. Some of the magnetic ores have varying amounts of martite mixed with the magnetite.

Summary

The known and partially developed orebodies of New York and New Jersey could, if equipped with the best modern mining and milling machinery and using the best methods, produce at the present time

25,000 tons of 60 per cent, iron ore per day. This can be delivered for an average freight charge of $0.75 per ton from mill to tidewater. The operating cost of production should reach the “dollar rock” ideal of the Lake Superior Copper region, and the cost of mining and milling 1 ton of crude ore should be about $1 for underground mining when handled in large quantities.

The ratio of concentration would be 2 tons of crude per ton of concentrates for an average. There are reserves of magnetic ore sufficient to double the above production, and then last probably 100 years.