Efficient filtration of fine kaolin particles plays a crucial role in processing of raw kaolin to a marketable product. Oftentimes, filtration is the rate controlling step of the whole process. As a consequence, plant production is dependent, to a great extent, on the rates being achieved in filtration..

Variation in particle size, coupled with varying amounts of impurities, present several challenges to processing kaolin and producing a product acceptable to the user industries. The major factors, other than particle size that affect the paper end use, are final Brookfield and Hercules viscosity, as well as brightness.

After mining, kaolin is crushed and slurried with water in a powerful disperser, or blunger. Here the pH is adjusted to neutral, and a dispersant is added. The slurry is then pumped to a gravity settling area or “drag box” where sand, mica, and other such impurities are removed. This process is referred to as degritting. After degritting, the slurry is blended and cut in to different size fractions using centrifugal classifiers.

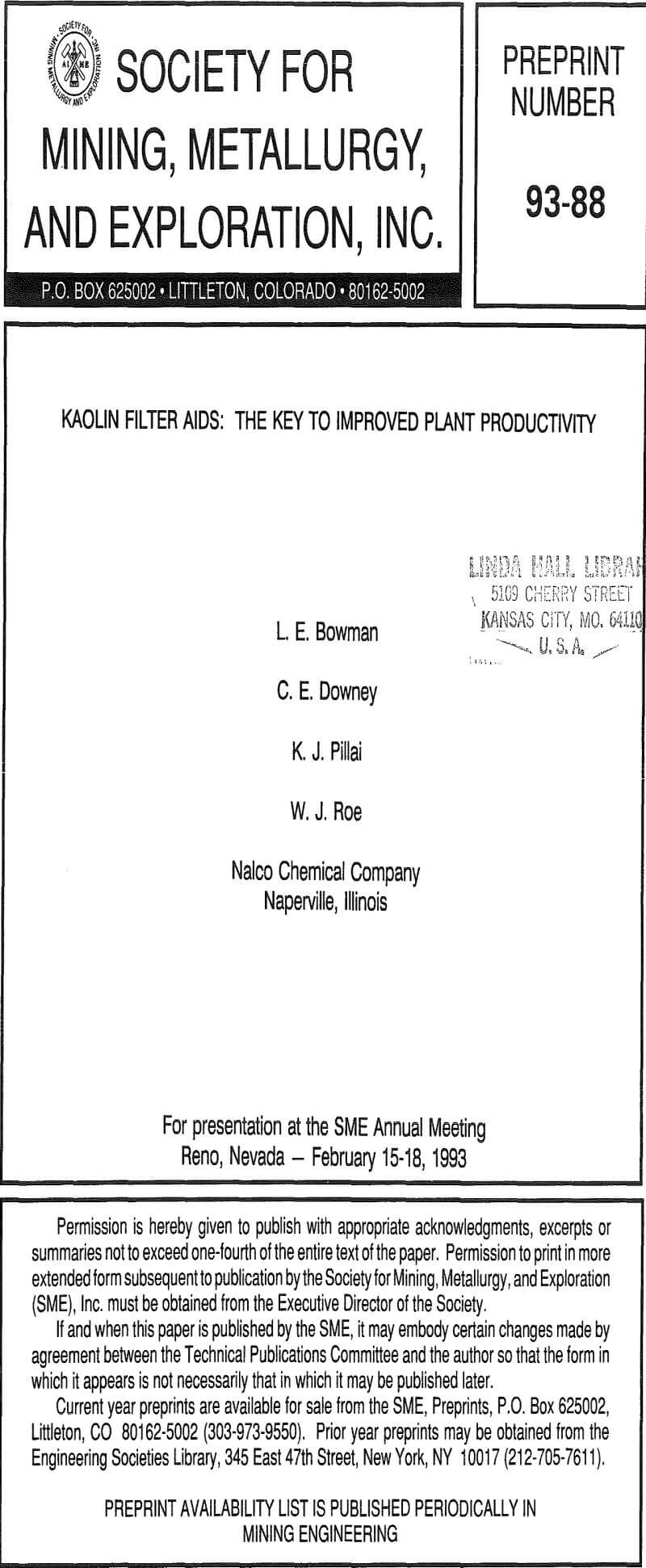

Due to kaolin’s small particle size, the vacuum filter production capacities are low. The filters average about eight tonnes per hour for a size distribution of 80% <2 microns, to three tonnes per hour for sizes of 80% <1 micron. As a consequence of low filtration capacities, most plants require a large number of filters which can be capital intensive. Energy requirements and manpower to operate vacuum filters are also quite high.

A standard filter leaf test as conducted by each plant was initially conducted until it was reproducible. In each case, the plant’s standard procedures were followed and used as the basis for comparison. Nalco reagents were added directly to the acid flocced slurry in the appropriate quantity and sequence and mixed for a minimum of 30 seconds. The optimum order of addition of the polymer was also determined. Filtration and drying times were initially kept the same as in the standard. These were also varied to determine optimum times. All tests followed the same protocol as each plant’s routine operation, with exception of the addition of the experimental reagents.

Several chemistries were tested for effectiveness as a filtration aid. The chemistries tested included 1) copolymers of acrylamide and acrylate with a variety of pendant groups of differing functionality, and 2) homopolymers of acrylamide, acrylate, and methacrylate. Several variations of these groups of chemicals were also tested as well as a series of new generation polymers and coagulants.

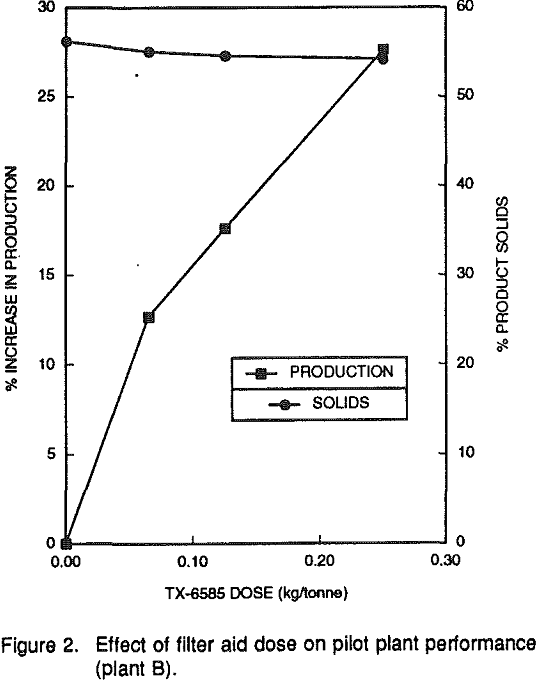

It is important to note that the decrease in filter cake solids was in the range of 2 to 3%. While this would increase the cost of thermally drying or calcining the product, the increased production rates provide a definite cost benefit advantage. Furthermore, NALCO TX-6585 did not have a noticeable impact on the viscosity of the redispersed filter cake and, hence, would not hinder the subsequent re-slurrying operation.

Filtration can be enhanced by either a flocculation or coagulation mechanism. The flocculants that showed activity also caused significant reductions in cake solids, and had a large negative impact on final clay product viscosities. Overdosing of flocculants increases the viscosity of the filter cake.