Rockers are widely used for washing placer samples and under most conditions they are well suited to the needs of the field engineer. It should be noted that since its inception, the American gold dredging industry has, for the most part, used rockers in preference to other types of sample washing equipment. The fact that the rocker has survived in direct competition with a variety of more “modern” or “improved” machines which have been introduced over the years attests to the reliability of results which can be obtained.

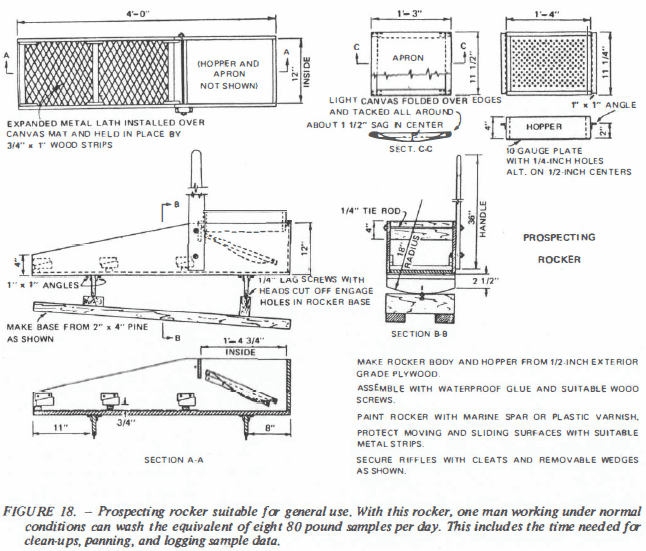

Rockers are usually homemade and are built in a variety of sizes and designs depending on the ideas and experience of the builder. Figure 18 shows a lightweight rocker which is easily built and is suitable for general use. Individual components are a screen-bottomed hopper for receiving and sizing the feed material, a canvas apron for deflecting the feed to the head-end of the rocker, the rocker body which is equivalent to a sluice, and a bed plate or frame upon which the entire assembly is mounted. A rocker may be made any convenient size because within limits, its size will determine throughput capacity rather than its efficiency as a gold saver. Although there are no fixed size criteria, a rocker 1 foot wide by 3 feet long would generally be referred to as “small” and one more than 18 inches wide or 5 feet long as “large.” When made of wood (which is usually the case) clear lumber without cracks or flaws must be used and the bottom should be made of vertical-grained stock which will not shred or rough-up when scraped. Heavy-duty rockers and those which are in continuous use are preferably made of sugar pine reinforced with suitable metal fittings. Where sugar pine is not available, redwood makes a fair substitute. Rockers made of exterior grade plywood have the advantage of lighter weight and they are strong and durable if the joints are sealed with waterproof glue. The exposed surfaces of a plywood rocker should be protected with marine varnish or spar.

The hopper should be made ½ to ¾-inch narrower than the inside width of the rocker; this results in a bumping action as the rocker is operated and assists scouring and screening the gravel. The amount of open area in the screen plate is important. A screen with too much open area allows the fines to pass through too fast and where much sand is present this can cause overloading of the riffles with resultant gold loss. A plate with ¼-inch holes drilled or punched in an alternate pattern at 1-inch intervals and on ½-inch centers will provide a screen with 10 percent open area. This has been found to be about right for small prospecting rockers.

The apron consists of a simple wooden frame covered with loose-fitting canvas or similar material. The resultant sag or “belly” in the apron functions as a gold and black sand trap and when large amounts of material are put through a rocker, the apron’s gold-holding ability permits longer runs between clean-ups. In normal sampling work where short runs made, the apron is less important and is sometimes dispensed with.

It is noteworthy that most old-time prospectors employed by dredging companies wash their samples in rockers without riffles. Experience and practice enable these men to concentrate the gold and black sand directly on the smooth wooden bottom of the rocker and, as a final step, to tail out the black sand and bring the gold to a point in a manner somewhat similar to panning. This technique is particularly useful when applied to small-volume churn drill samples and is mentioned here to point out that a properly operated rocker is an excellent gold saver which unlike the sluice, does not rely on riffles for its effectiveness. But it should be pointed out that a rocker equipped with good riffles will forgive much mishandling and, for this reason, the average person should use them. Parenthetically, it should be noted that even the experienced rocker operator, in certain cases, may find it more expedient to use riffles than to explain to a layman why they are not essential. A simple riffle arrangement suitable for general use can be provided by covering the rocker bottom with heavy-gage expanded metal lath placed over a canvas mat and held down by several transverse wooden slats as shown in Figure 18.

The length of the rocker handle is important-it should be waist-high to the operator in a standing position. The long leverage thus provided makes the rocker much easier to handle and materially reduces the physical effort which, at best, is considerable. Anyone who has attempted to operate a short-handled rocker from a sitting position will appreciate the foregoing comment.

Like panning, rocking relies to some degree on subtle techniques which must be learned by experience but the following pointers may help the novice get off to a good start. The first step is to set the bed plate and secure it so that it will not shift or move around when the rocker is in operation. The best slope for the rocker will have to be determined by trial but if it is initially set at 1½ inches fall per foot of length, a few short trial runs will suffice to make any needed adjustment. Insufficient grade may cause sand to blanket the riffles and result in loss of fine gold. If the hopper is filled too full, gravel will slop over the sides when rocked and it will be difficult to regulate the flow of material through the screen and, for this reason, the hopper should not be filled over half full and preferably the screen plate should be left partially exposed at one end. Starting at the exposed end of the screen plate, water is poured over the gravel while the rocker is shaken vigorously and the amount of material fed to the riffles is regulated by shifting the point of water application back and forth between the gravel and the exposed screen plate. Most pictures illustrating the use of a rocker show the water being applied with a long-handled dipper such as a gallon can on the end of a stick. In practice one finds that it takes considerable dexterity to use a dipper and at the same time operate the rocker smoothly and maintain a uniform flow of material over the riffles. For this reason, a water hose supplied by a pump or a gravity-flow should be provided where possible. The flow of water obtainable from an ordinary garden hose (about 5 gallons per minute) is usually enough for operating a rocker but where this is not available, two or three barrels of water used in a closed circuit will generally be sufficient for a day’s work. When water must be dipped, the water barrel should be placed next to the head-end of the rocker within easy reach of a short-handled dipper.

When rocking is periodically stopped to discharge rocks from the hopper, the material passing over the riffles will settle and tend to pack, particularly if much black sand is present. If washing is resumed without first loosening this material, any fine gold that has not penetrated the packed sand will be lost with the tailings. To guard against this, the material behind each transverse riffle should be loosened and scraped back toward the head end of the rocker with a flat, straight-edged scoop. This loosening procedure is the key to effective rocking. The loosened material is subsequently washed down and re-concentrated with the next run and if the rocker is kept free of packed sand in this manner, it will effectively recover flour gold particles running 1,000 or more to the cent.

After the entire sample has been washed, the concentrate remaining behind the transverse riffles is picked up with the scoop and placed in the upper end of the rocker and then carefully re-washed once or twice with clear water to remove surplus sand and further reduce the concentrate volume. The apron, riffles and canvas mat are then removed and washed out in a pan or tub of water and the combined concentrate panned to a finished product.

Although reference books state that from 1 to 3 cubic yards can he washed in a rocker per man-shift, it should he noted that these figures apply to production-type work and give little indication of what should be expected when processing samples. Experience has shown that one man using a 12-inch x 4-foot rocker similar to the one illustrated in Figure 18 can wash the equivalent of eight 80-pound samples per day where conditions are favorable. This includes the time for clean-ups, panning, and logging sample data. The total amount will, of course, vary with the size or number of individual samples and with the character of material being washed. Material containing much clay can halve this figure whereas loose, free-wash type material may double it. Dredging companies occasionally use large, engine-powered rockers in which the total gravel excavated from a shaft can be washed rapidly and economically. A typical power-driven rocker having a capacity of 5 cubic yards or more per 8-hour shift is illustrated and described on pages 334 and 335 of the August 25, 1923, issue of Engineering and Mining Journal-Press.