Although the subject has no practical bearing on the metallurgy of the present day, it may not be entirely uninteresting to note how the art of silver-lead smelting has been, and in a few remote districts of Peru is still practiced by an old method, and under conditions widely different from our own.

The subject will be considered under the following subdivisions: The general conditions; construction and plan of furnaces fuels and ores; method of working; furnace products and slags.

The mineral region of Peru varies in altitude from 10,000 to 16,000 feet above sea-level, comparatively few mines being located, above or below these limits. The timber-line in the valleys is at about 12,000 feet altitude on the western slope of the mountains, and even there the supply of wood is not sufficient to be utilized as fuel for furnaces. The sides of the mountains are either bare or covered with a hard bushy grass, which is most luxuriant during the latter part of the rainy season, from February to April.

Agriculture on the western slope rarely reaches above 12,000 feet, while on the eastern slope its limit is at 14,000 feet; and in either case the height named is reached only in sheltered places.

Transportation is slow, being carried on mainly by llamas, donkeys and mules; the former (taking 100 pounds at a load) are almost exclusively used for carrying ores; the latter for agricultural products, merchandise and travellers. The cost of transportation has prevented, and in many localities still prevents, lead and copper from being exported, thus influencing very perceptibly the mode of smelting.

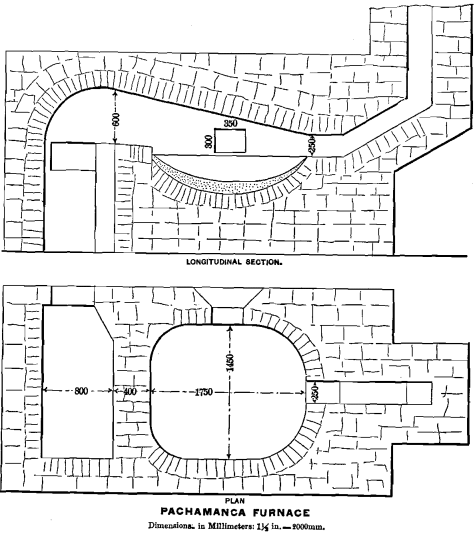

The furnaces, called by the natives pachamanca furnaces, are constructed in the shape of a small reverberatory, with a shallow basin like that of a cupelling-furnace. The accompanying sketch from the new, nearly completed furnace of Senor Vila in Cerro de Pasco fairly represents their general construction, apart from small variations of size, made according to the requirements of the smelter.

The material used consisted of any fire-proof rock found in the region, and clay for the lining, while the outer parts were built of ordinary stone and a crude mortar made of burnt lime and sand.

To replace the wooden centers necessary for constructing the arch, the furnace was built up to the spring of the arch, then filled with sand, the upper surface of which was formed to the required curve, which was generally quite flat. The arch was then completed, and after it had duly settled, the sand was drawn out. Sometimes, when good clay was at hand, bricks were used in the construction. The chimney, 10 to 18 feet high, was generally made of adobes, and the entire furnace was enclosed in an adobe house with a thatched roof, the timbers for which, brought from the wooded regions, formed the most costly part of the house. Sometimes advantage was also taken of overhanging rocks for protecting the furnace partly or entirely. The doors and dampers were formerly made of flat stones, but now sheet-iron is often used. The furnace-tools were few and simple, consisting of a poker, a scraper, a rabble and a paddle-shaped spatula for withdrawing litharge in cupellation.

The fuels consisted mainly of dried llama-dung, called taquia, gathered by the Indians during the dry season and placed under shelter. Sufficient heat can be produced with it to roast and smelt ores. It is generally fed in such a manner that a small quantity is constantly being thrust rapidly through the fire-door with a thin board or sheet of tin; this operation having also the advantage of producing at the same time a slight draft. In some localities, where coal or bituminous shale can be had cheaply, as in Cerro de Pasco, it is used with advantage. Wood as a fuel is out of the question, on account of its great cost. The fires were generally started with dried grass, and, when necessary, were kept low for a long time by covering the embers. As the furnaces have no grates the fuel remains as a glowing mass in the fireplace, the heat rapidly igniting most of the fine taquia before it falls to the bottom.

The ore principally used was galena, generally assaying 37 to 95 ounces of silver per ton (a fair average would be 50 ounces per ton), and from 35 to 55 per cent, of lead. Gray copper was, however, used very largely, assaying at different mines and with varying degrees of care in sorting, 85, 158, 177, 240, 315, and 630 ounces respectively; the first three figures being the most common, while the others can only be attained in a few places, and with very careful work. Ruby-silver and native silver, as well as argentite, were of course utilized whenever they were available. It is probable that the upper portions of the old mines which were largely worked by the Spaniards before the War of Independence in Peru in 1822, contained the richer and more highly oxidized ores, thus facilitating extraction considerably.

In working a new furnace, it was first air-dried; then the fire was started, and a gradually increasing heat was kept up from three to four days, after which the first charge, consisting of 100 to 125 pounds of lead or litharge, was melted and reduced, and allowed to soak into the bed of the furnace. Then two to three charges, weighing about 400 pounds each, and consisting mainly of easily-fused material, such as lead carbonate or litharge, were reduced; after which the regular charges of 500 to 600 pounds of ore were given. The crushed ore would mostly pass a 3/8-inch screen, a few pieces, perhaps, remaining on a 5/8-inch screen. Oxidized ores were immediately slagged with a strong fire, while sulphide ores were charged at low heat, spread uniformly over the bed and roasted, sintering being carefully avoided. Then stronger heat was given, and the charge was slagged. Both operations together required about four hours. The slag was then drawn and the lead was cupelled, this process taking from seven to eight hours. With poor charges, several smeltings were made to one cupellation. In the latter process the litharge was not generally permitted to flow from the furnace, but was allowed to form on the paddle-shaped spatula above mentioned, which was then withdrawn and allowed to cool. The litharge was knocked off and saved. When cupellation was completed, the furnace was cooled a little, and the solidified bullion was removed. Artificial draft, excepting that produced by the chimney and in adding the fuel, was not used.

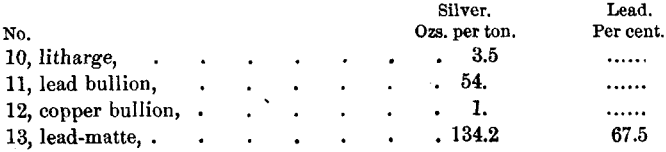

Of the furnace-products, traces of the silver bullion have been found on pieces of hearth in old slag-dumps. The litharge was utilized in the reduction of rebellious charges or in starting new furnaces, and is, therefore, comparatively rare, though the yellow and red litharge can readily be distinguished when present. Although no examples of the formation of copper- and iron-mattes have come to the writer’s notice, there can be little doubt that they were occasionally formed, and were re-treated like sulphide ores. One instance of the intentional formation of lead-matte has been noted in a new furnace. The object was simply the concentration of the ore for the reduction of the freight-charges. An assay of this matte is given below.

In some of the old dumps small pieces of lead bullion and metallic copper have been found; but these can only be considered as accidental by-products, being practically worthless under the conditions of working, except, perhaps, as to small quantities for domestic use.

The slags are the most interesting and abundant remains of these old works. They were thrown on the dump regardless of the high quantity of lead they contained, and serve to indicate the quality and quantity of the work done. In age, they differ considerably, as in some places the furnaces are working at the present time, while in others no trace of the building remains, and only the slag-dump marks the site of former activity; and again, in some localities, successive furnaces have been constructed on the ruins of earlier ones, the latest often being in a fair state of preservation. Hence, of these dumps, some are quite modern; others are from thirty to forty years old; many antedate the stoppage of operations at the Revolution, seventy years ago; and the age of some of them can safely be estimated at one hundred and fifty years.

Of the numerous localities in which smelting has been done, only a few, which were personally observed, will be mentioned here, viz., Yauli, Bellavista at Chicla, Cerro de Pasco, Humanrauca Vinchos, Visco, Huayro-Cancha, Morococha, and Santo Domingo.

The slag-dumps vary considerably in size, according to the amount of work done. In some localities they have been covered up with debris or carried off by freshets. In many instances only a few tons were seen; in others, possibly 10,000 tons; very rarely more than 20,000, and in but one case 100,000 tons.

Some years ago the attention of the neighboring miners was called to the value of these slags, and, in consequence, the dumps were taken up as mining claims. In some places where large dumps exist and fuel is cheap, furnaces have been constructed for reducing them, either alone or in connection with silver-ores.

The general character of the slags is nearly the same in the different regions, the most common being a hard solid slag, having a stony-gray color. There are also three brittle classes, respectively glassy-black, dull-black, and brownish-red ; the latter the rarest in occurrence and highest in lead, being probably the last slag drawn before cupellation.

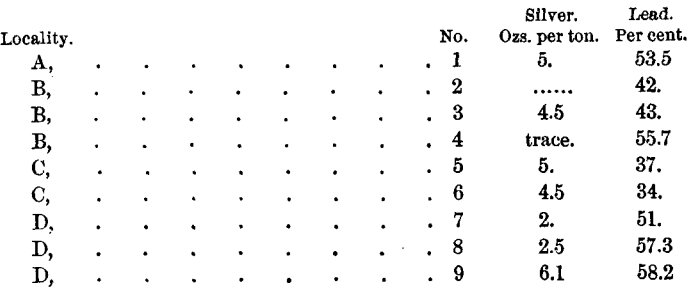

In furnaces now working, an orange-yellow slag is often produced. It is unusual for slags to be porous, and they are then only of the first-class above mentioned; and it is still rarer to find particles of raw galena in the slag. Assays of some of the slags gave the following results:

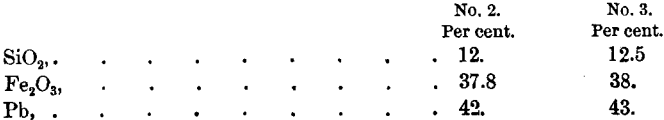

Of Nos. 2 and 3 a rough analysis was made to determine the iron oxide and silica, which, with the lead, constitute over 90 per cent, of the slag; the remainder, consisting of sulphur and lime, was not determined. The lead is taken from the assay :

In other products the following results were obtained :

These few remarks, though very far from being exhaustive, will at least serve to give some idea of the system of smelting employed by the Spaniards in Peru.