Torches were used by the early Romans for mine-lighting, and these were followed by open lamps or earthen jars filled with tallow or oil, and later by candles. In early coal-mining, explosive gases seldom occurred, and, if they were encountered, the danger of explosion was materially diminished by the absence of any ventilating-system and the consequent insufficient circulation of air to form with the methane an explosive mixture.

As the art advanced, the danger of fire-damp became more apparent, and methods for testing the air were resorted to as early as in the fifteenth century. The method of testing consisted in lowering a dog in a basket down the shaft. As soon as he encountered fire-damp he would commence to howl, after which he was withdrawn, and a leafy bush was fastened to the end of the rope and run rapidly up and down the shaft. This so disturbed the accumulation of gas as to cause it to rise out of the shaft. Later this odd method of testing was improved upon through the discovery that a light inserted in a body of fire-damp would produce a blue flame. Candles were used for this purpose, and, when fire-damp was thus discovered, brushing or some other primitive method of fanning was resorted to for driving out the gas. In some instances the gas was burned away, regardless of the danger thereby incurred. A man, wearing a well-moistened coat and a mask with glass spectacles, descended in the mine a few hours before each shift. With a long stick, to which was fastened a burning torch or candle, he would crawl on the floor with the stick so raised that the light would sweep the roof and ignite the gas which it encountered. In this position the flame of the explosion would pass over him, after which he would retreat from the gases resulting from the combustion. The occurrence of serious accidents resulted in the substitution of a method by which the candle was moved along the headings by means of an endless rope, which was supported on pulleys near the roof and could be operated from a safe point.

In 1815 Davy invented the safety-lamp which bears his name and the principle of which is embodied in the numerous safety-lamps of later inventors. Although many improvements have been made in the safety-lamp, it is still far from perfect; and the present indication is, that, in order to obtain a perfectly safe and reliable lamp, the electric light must be resorted to.

In metal-mines, and even in coal-mines where the gases contained in the atmosphere are sufficiently diluted to render them harmless, illumination may be had by any form of naked light. But in collieries where considerable quantities of firedamp and coal-dust are liable to collect, the lamp-flame must be protected from direct contact with the gas, and it becomes necessary to use some sort of safety-lamp.

The most common of all miners’ lamps is the small tin lamp which generally is carried on the miner’s cap. A cotton wick extends through the spout into the fluid, which is generally some kind of petroleum-product. While this lamp, when trimmed and kept in order, gives a fairly-good light, the objections to its use are many. The almost continuous smoking seriously impairs the purity of the air and thus handicaps the miner in his work. It is easily blown out by blasts and drafts. The leakage of oil from the lamp is a constant annoyance, and the time required for refilling and trimming the lamp is considerable.

The acetylene lamp, used to a considerable extent in a number of mines, is a marked improvement on the oil-lamp. Not only is the illumination materially better, but the smoking and leakage of the oil-lamp are practically eliminated. The difficulties of handling seem, however, to have prevented its general adoption.

In mines liable to the intrusion of excessive amounts of fire-damp, safety-lamps must be used, either exclusively, or for purposes of inspection, preliminary to the removal of the gas. Several types of safety-lamps of more or less ingenious design have been placed on the market and are in actual use in the various gaseous coal-mines.

The Davy is an ordinary oil-lamp, the flame of which is surrounded by a cylinder of wire gauze, with a top of the same material. The principle of this lamp is that the cooling effect of the wire gauze prevents the propagation of the flame from the inside of the lamp to the outside atmosphere. After the lamp has been filled with oil and lighted, it is locked, so as to prevent the miner from having access to the flame, the wick of which is trimmed by a wire passing up through a close-fitting tube from the bottom.

The Clanny lamp is similar to the Davy, with the exception that the lower portion of the wire-gauze cylinder is replaced by a short glass cylinder, giving a somewhat better illumination.

Stephenson’s lamp has a long cylinder of glass surrounded by wire gauze, and bonneted above by perforated copper. The air-feed is also through the gauze, going underneath and into the cylinder to the flame, thence out of the top as usual. This keeps both cylinder and gauze cool, and its relative security rests essentially on the regularity of the draft, for if the inside air becomes overheated the light goes out; so it must be suspended properly.

The Marsaut lamp is an improvement upon the Stephenson type, and can safely stand a fair amount of tilting. A great difficulty is, however, experienced in relighting it, and from the winding path pursued by the feed-air, proper circulation does not take place until the lamp gets hot.

The Hepplewite-Gray lamp admits the air at the top, down four tubes, and through an annular chamber above the oil-vessel. The only gauze employed is that covering the outlet and the annular inner chamber. A serious difficulty with this lamp is its liability to be extinguished when suddenly lowered.

In the Dick port-hole lamp, the air enters the lamp above the case, passes through the gauze, then descends to the flame, while the products of combustion rise inside the lamp, to be emitted through circular holes at the top of the bonnet. The bonnet is made of a seamless steel tube, and is light and strong.

The Wolf benzine safety-lamp is a departure from the above safety-lamps in that: (1) it burns benzine or naphtha; (2) it contains a self-igniter which permits the relighting of the lamp 50 times without opening; and (3) it contains a locking-device which cannot be opened except by the use of an exceedingly powerful magnet.

While the safety-lamp possesses great value as a gas-detector, it is open to several serious objections. The first is the possibility that the gas, entering the lamp, and burning inside the cylinder, may overheat the gauze, which will then permit the flame to pass through it. Several types of lamps, however, are arranged to be self-extinguishing in case of ignition of gas inside the gauze. This is, of course, objectionable, as it will leave the men in darkness when such a danger occurs. The temptation of the miners to relight extinguished lamps, or open them for lighting pipes, etc., is very great, and has in many instances resulted in serious explosions. Finally, the illuminating-power of the lamps is very low.

For the above reasons safety-lamps of the ordinary type are being replaced in many localities, especially in bituminous coal-mines, by portable incandescent electric lamps. This type offers numerous advantages: increased safety in explosive atmospheres; increased illumination, ability to concentrate the light on a certain area, reliability and simplicity, elimination of smoke, cleanliness, smaller fire-risk, etc. An objection often raised against the electric lamp is that it offers no means of indicating the presence of fire-damp. Several devices have been proposed, such as providing spiral wires coated with salts of platinum, etc.; but there seems to be at present no really satisfactory solution of this difficulty, although there is no reason why a solution should not be expected. To attempt to find a satisfactory fire-damp indicator is, however, merely to delay the general introduction of electric lamps; and there seems to be no real necessity for such an addition to a miners’ lamp. The fire-damp detector might well be an entirely separate instrument, which could be installed in places where the fire-damp is expected to form first, such as near the roof, or in cavities therein. There is no reason why one or more gauze-lamps should not be supplied with each batch of electric lamps, and hung in the working-place where they can be easily seen, and where any outburst of gas would be most likely to occur.

Numerous electric mining-lamps have been designed, but few have proved efficient and durable. The design in the United States and abroad has followed very different lines. In Europe the hand-lantern has been almost exclusively considered, while the tendency here has been towards the perfecting of a combined hand-lantern and head-light. This is the logical result of the fact that the most satisfactory working-results can be obtained by a head-light, whose reflector concentrates and throws the light in the direction in which the miner works.

A new electric miners’ lamp of improved design has recently been developed by the General Electric Co. to meet the increasing demand for a safe and reliable lamp. The idea of a systematic investigation as to the possibilities of developing such a lamp originated with W. J. Richards, Vice-President and General Manager of the Philadelphia & Reading Coal & Iron Co., to whom credit is due for his very active assistance.

The lamp is of the combination hand-lantern and head-light type, and consists of a miniature tungsten lamp-unit, operated from a light storage-battery. The lamp is provided with an efficient reflector, designed to illuminate a 9-ft. circle at a distance of 4 ft. from the lamp, and photometric records show about 2.5 or 3 candle-power at a distance of 2 ft. The battery has a capacity of 5 ampere-hours, and is of sufficient size to operate a lamp from 12 to 14 hours.

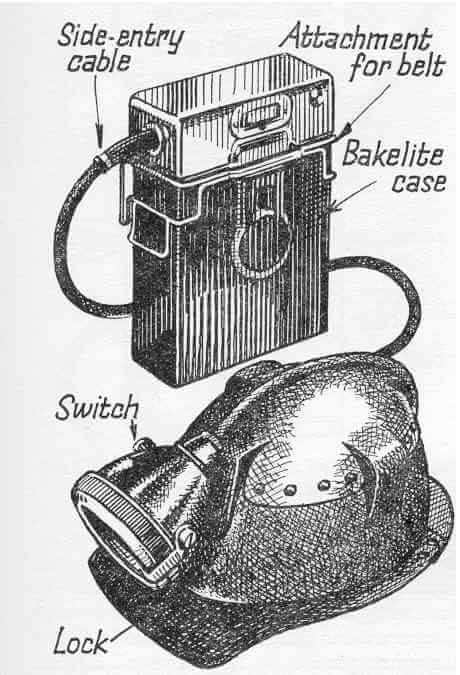

When used as a head-light, the lamp, with its reflector, is fastened to the miner’s cap, and connected by means of a flexible cord to the battery, which is carried on a belt or from shoulder-straps, as shown in Fig. 1. When used as a hand-lantern, Fig. 2, the lamp-socket is removed from the cap-receptacle and inserted into the receptacle on the side of the battery, simply taking the place of the cable-attaching plug.

Some of the important points in connection with this design are: substantial construction; light weight and compactness; complete inclosure of all conducting parts; use of an absorbent for the electrolyte, to prevent spilling; small number of movable contacts; increased efficiency of a 4-volt lamp; efficiency of the reflector; impossibility of charging with reversed polarity; instant convertibility from hat-lamp to hand-lantern. These features will be considered in the order in which they have been mentioned.

Special care has been taken to select all materials used in the construction to withstand the hard service to which this lamp may be subjected. The steel battery-case is drawn from a single plate and is, therefore, seamless. The battery-jar is not of the brittle rubber commonly used, but has some elasticity left in it, so that, should the steel case receive a blow, there is little chance of the battery-jar being cracked. The cord from the battery to the lamp is metal-armored where the greatest wear and strain occur, but perfectly flexible where flexibility is required. The battery-case is locked with a magnetic lock which also locks the attaching-plug in the receptacle, thus preventing this plug from working loose and permitting the formation of a spark. The hat-lamp is sealed with a lead seal, which must be broken before the miniature lamp-globe can be removed.

This outfit has been designed, as already explained, for use as a head- as well as a hand-light, and therefore the weight of the battery, which must be carried on a belt, in the pocket, or by shoulder-straps, has been kept at a minimum consistent with strength and durability. The battery is flat and compact in order that it may lie as close as possible to the body. It weighs approximately 3 lb. and measures 6½ by 4 5/8 by 1 1/8 inches.

In order to prevent accidental short-circuits, causing sparks, all live parts are totally inclosed in molded compound. The battery-terminals, attaching-plug, hat-receptacle, and lamp-holder are all molded from hard fire- and acid-proof compound and thus perfectly protected from corrosion due to acid spray or gases.

An absorbent is used for separating the battery-plates and also filling up the extra space in the battery, except the mud-space. This absorbent acts like a sponge and holds the electrolyte in the battery even though it be inverted for some time.

Where low voltages are used, the pressure-drop caused by the contact-resistance may be serious. The movable contacts in this lamp have, therefore, been reduced to a minimum and have been so designed that they come together with considerable pressure.

The increased efficiency and life of the apparatus is principally due to the improved tungsten lamp. A 2-volt lamp is somewhat inefficient and has a comparatively short life. This is due to the cooling effect of the large leading in wires on the short filament. This cooling by conduction reduces the temperature of about one-third to one-half of the filament to a point where little or no light is produced. In order to produce the rated candle-power, the rest of the filament must be operating at a temperature far above a safe value, with a consequent unreliability and shortening of life. The filament of the 4-volt lamp, for which this outfit is designed, is about twice as long as a 2-volt filament, so that the percentage of length cooled by the leading-in wires in a 4-volt lamp is about one-half that in a 2-volt lamp. This allows the rest of the filament to be operated at a safe temperature, giving a reliable lamp of long life. The filament is, however, not so long as to cause mechanical weakness.

The reflector is made of stamped steel, enameled both inside and outside, thus absolutely protecting it from corrosion. Tests have shown that white porcelain enamel forms one of the best possible reflectors, and is very durable and easy to keep clean. The lamp-globe is protected from injury by a glass plate, fastened to the rim of the reflector by a spring. This glass further tends to prevent dust from accumulating on the inside of the reflector.

The contacts on the battery-terminal and plug are made concentric, so that, no matter how the plug is put in, the polarity must be the same each time. A separate plug is supplied for use in charging, and can be wired permanently on the charging-rack with its polarity correct. It will then be impossible to charge the battery from this plug with reversed polarity.

While the demand for an electric mine-lamp seems to be almost entirely for one to be worn on the cap, to supersede the present oil-lamp, it appeared very desirable to have an outfit that could quickly and readily be converted into a hand-lantern. This has been accomplished by designing the lamp so that, by a quarter-turn, it can be removed from the hat-receptacle and inserted, by a quarter-turn, into the plug-receptacle on the side of the battery.