The only minerals of any importance which are found in alluvial deposits are gold and other precious metals, tinstone, and those gems which by reason of their hardness and power of resisting chemical changes are preserved in their original state even after being scoured by water for long periods. It is now generally conceded that these alluvial mineral deposits owe their origin to reefs, though it is quite possible that nuggets such as are found among the gold dust far away from any possible reef source have been deposited by chemical and electrical agency. The probable great age of these alluvial deposits must not be lost sight of. Most theories as to old river-beds relied upon by alluvial prospectors of the old school are wrong. The gold was probably eroded from the parent reef at a very early period of the earth’s history, and has since been carried by water in different directions over the earth’s surface, so that the existence of alluvial gold will often afford no clue as to the reefs from which it originally came. The transportation of gold from the reef has gone on for countless ages, a time geologically short, but inconceivably long in comparison with the lives of men. The Andes, for instance, have been piling their debris about their own feet since first the Cordilleras began to rise out of the level plain. Dr. Evans, when working in the Bolivian foothills, observed that gold was more frequently met with in the ground just below the gorges, which proves that at such places the gold must have undergone a second and perhaps a third concentration, as nature undoubtedly in the process of time begins to cut down each successive elevation that rears itself above the normal level.

An instance of the fallacious theories which lead men astray was afforded by the Mangles River, a tributary of the Buller River, N.Z., in which some very rich alluvial occurred near the confluence. Near Macgregas the conglomerates of the local coal measures cease, and above this point little or no gold exists. The origin of the river-bed gold is, therefore, apparently quite clear, and many miners have spent much money and labour in unsuccessfully prospecting these cretaceous coal measures for reefs. They appear to have quite ignored the fact that the gold was probably derived from the conglomerates and simply concentrated, and that the rocks are not such as would be likely to contain reefs. In British Columbia, also, a great deal of prospecting has been done for reefs in the vicinity of rich alluvial deposits, but with little success. In this case, however, the fact is that the gold has probably traveled a very considerable distance from its source, and the first part of its journey having been accomplished in icebound masses of earth it has not worn sufficiently to give an idea of the distance it has travelled.

The one distinct variant of alluvial deposits is the existence of beach deposits in certain parts of New Zealand and other places, where gold is found mixed with black sand about low-water mark. These deposits have hitherto been worked by means of a portable sluicing table which is wheeled down to the water’s edge at low tide. The concentrative action of the sea on these beaches is such that after every big storm the gold in the black sand is renewed.

A discovery of great interest was made by Sir Martin Conway while investigating the tributaries of the Kaka, in Peru. The upper reaches of that river are within the torrential zone and contain fair gold. Four tributaries unite almost simultaneously just below this zone, and the river proceeds to flow through a narrow rock gorge in the bed of which practically no mineral can remain. It occurred to Sir Martin that below this gorge there would probably lie a large alluvial deposit which would have been reconcentrated and made richer by the action set up by the gorge. The place was accordingly prospected by a competent miner, and the most astonishingly rich prospects were obtained. The ground has been taken up, and is now being worked by both English and American mining companies. The same remarkable phenomenon exists in the Lower Inambari, Peru, district, where the richest alluvials have been discovered well outside and below the area which was originally investigated by the prospectors and thought to be the main auriferous region.

There are other points which render it necessary for prospectors of companies who are contemplating the erection of dredges to be exhaustive in their researches and enquiries. Often enough big concessions have been taken up on the evidence of natives who are known to have recovered good gold and made a living by means of the pan. In Colombia, Peru, Korea, Tierra del Fuego and other places vast quantities of alluvial have been proved to exist which after trial have been found to be unworkable. In most cases the reason is that the rivers are torrential and full of boulders, and, therefore, totally unfit for dredging operations. In other cases, of course, they are on flats which are dredgable, but which do not come within the sphere of the hydraulic miner. In Ashanti the natives have doubtless recovered large quantities of gold in bygone times. Their method was to sink a shaft down as far as possible either to bedrock or water level, and to extract the coarser gold from the richer gravels. Their labour was forced, and, therefore, gratuitous, and their idea of “ richness ” was vague, so that their reputed results cannot be relied upon. The operations of dredges on the Offin River have proved that the mere existence of such holes does not indicate wealth, and it has been found that where the natives have gone to bedrock, as is frequently the case, the reason has been that it has been dry, which fact almost invariably means that it is above the river-bed from which the dredge could work, and is still rising, which means that it would be impossible to do even paddock work.

In the Republics of Colombia (Tolima) and Panama (Darien) there are huge tracts of country which appear to have been vigorously worked by the Spaniards, and which have been eagerly taken up by English and American syndicates, but which were originally worked by slave labour and have proved themselves to be unpayable under modern conditions.

The exact amount of overburden cannot be gauged over any big area, and many drill tests are necessary both to establish that fact and to prove the various depths at which bedrock is to be found. The latter information is very essential, as in dredging a sudden rise in the bedrock will often at once make it impossible for a dredge to work. It is quite common to find men who believe that bedrock lies as far from the surface at one spot on an alluvial field as it does at another, or that the thickness of the overburden is the same all over big stretches of country.

The factors that should be considered, therefore, are very various, and are as follows:

- The accessibility of the dredging ground.

- Cost of transport.

- Cost of local labour.

- The existence of boulders, bars of rocks, and submerged trees, the first two of which will often preclude the possibility of successful dredging.

- The proximity of firewood or other fuel.

- The cost of clearing the adjacent ground.

- The depth at which bedrock lies and its nature.

- The depth of the overburden and

- The thickness of the gold-bearing gravel.

The only things that are necessary to establish these facts are intelligence and observation, a good knowledge of the country, a “ keystone ” or other drill, and a few shafts driven here and there for the purpose of corroborating the results of the drill tests.

Prospecting for Alluvial Gold

The great trouble in connection with most prospecting operations has always been that most soil contains gold in very variable quantities. The ordinary drill test must always be misleading in consequence of this, and an occasional shaft with a diameter of about 3 ft. is necessary for the purpose of checking the drilling machine. It is hard to speak definitely or comparatively of the performances of drills, because the nature and composition of the ground and the efficiency of the drilling crew influence the results so largely ; but it is safe to say that with the ordinary modern apparatus a gang of skilled hands should bore from five to six holes per day, the holes about 50 yards away from each other, to a depth of say 30 feet, if the soil is composed of sand, clay and gravel. As the depth increases the time expended, on account of the ticking out and replacing of tools, also increases.

These figures will not be approached in many countries, such as West Africa, where the native labourer is a stupid and ignorant person and very hard to teach. In many places, such as Surinam, the native is constantly looking for fresh work, and a gang cannot, therefore, be trained with that continuity which will alone ensure good and rapid work.

Innumerable drilling tests which have been followed by the dredge itself have proved to be of only problematic accuracy. The Ashanti Goldfields Aux., Ltd., dredged ground thus tested in 1907. The bore-holes had given from five to eleven and thirteen grains per cubic yard, but the results achieved by the dredge never gave more than two grains. In that case it must be admitted that sufficient care was not taken to feed clean water to the tables, and the paddock water became so dirty as to be able to carry off fine gold. Another dredge (New Zealand) is recorded as having recovered only 40 per cent, of the values indicated by the bore-holes.

The only case of which the writer ever heard in which a dredge verified the drill tests was in California, where a new modern machine obtained 92 per cent. Many of the Californian experts think that a drill test which sinks a 6″ hole, gives, if worked by reliable operators, a test fully as accurate as a shaft. There is no doubt, however, that prospecting by shafts is the most satisfactory as with them it is possible to get an idea of the size and character of the gravel, and, of course, a much larger area of bedrock is exposed. It is held by some prospectors that the action of the boring plant is such that the flow of water down the rods is liable to carry away a certain amount of gold, but it is quite certain that in all cases where a sand-pump forms part of the equipment the gold brought up may have been largely obtained from the surrounding gravel. The procedure followed and spoken of by Mr. Newton Booth-Knox in a paper read by him in 1903 was as follows :—

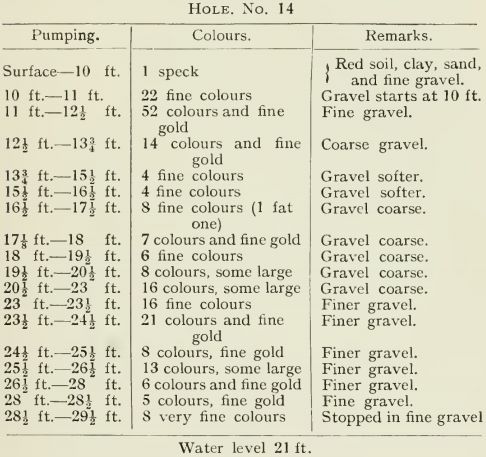

“The drillings extracted from the drill hole by means of the sand-pump are discharged into a wooden trough, 12 ft. by 1 ft. by 1 ft., set on a slight grade. From the trough they are run into the riddle of a rocker, and rocked in the ordinary method adopted for washing gravel. Great care is taken to save all the extremely fine particles of gold, as upon this work depends the accuracy of the tests made. It is customary to clean up results of each pumping, and carefully to note the number of countable colours obtained, and the character of the ground drilled through.

“For instance, a page of the driller’s notebook taken from actual practice is as follows:

“ The term ‘ fine gold ’ is applied to such specks as are too small to be counted, but which play an important part in making up the total value of the hole. The gold from each clean-up is put in a small dish.

“ This practice of cleaning up after each pumping (approximately after each foot drilled) instead of one final clean-up is all important in furnishing data for a cross-section map showing the occurrence of rich streaks, sandy or clay patches, depth of overburden, of false bedrock and of water level.

“ After the last clean-up all the gold from the holes is collected by means of quicksilver forming an amalgam. This amalgam is dissolved in nitric acid and thoroughly washed in hot water. A few drops of alcohol added to the wash water will prevent spattering and loss of gold when the last drop of water is evaporated. The gold is annealed and carefully weighed. From this weighing the value of the ground at this particular spot is calculated and the results given in cents per cubic yard.”

The ideal boring apparatus, in order that it may be easily transported, should be very simple and divisible into parts of not more than 56 lbs. each. It should be capable of working, either by the use of light boring frames or through the well-hole of a dredge pontoon, or through the casing of any other type of vessel. It should be as capable of working in deep water or in marsh land as in firm exposed soil. No tool of any  description should ever be allowed to rest in the bore-hole during meal hours or at night time. Especially is this the case when working in sandy soil, as it may cause the tools to become stuck in the pipe, which circumstance generally makes it necessary to take everything out and consequently a lot of time is wasted. Care must be taken that the bore-hole is always kept quite vertical, otherwise at a certain depth the tool will refuse to drive properly. This is especially the case when going through ground containing boulders, which tend to deflect the drill head. To obviate this, the “ Keystone drill ” is fitted with a tool called a “ jar ” between the rock socket and the stem. It is like two links of a chain and when the bit is caught these two links come together with a shock, and jar the drill loose. As the value of the ground can only be determined by examining samples taken at regular distances, to be fixed by the nature of the stratum and the presence of the mineral, it is desirable that the tools bring up only such earth as is contained in the cylinder, and it is, therefore, essential for the tool to bore and the case to drive quite simultaneously and as nearly as possible at the same level. In calculating the values it is best to adopt the practice general in California, where the local engineers hold that the outside measurement of the case should be taken. They say that it is the displacement of the pipe and not the cubical contents that should be taken. In practice it is found that by taking the inside diameter of pipe the result is too high, and is never actually borne out by the results actually achieved by the dredges.

description should ever be allowed to rest in the bore-hole during meal hours or at night time. Especially is this the case when working in sandy soil, as it may cause the tools to become stuck in the pipe, which circumstance generally makes it necessary to take everything out and consequently a lot of time is wasted. Care must be taken that the bore-hole is always kept quite vertical, otherwise at a certain depth the tool will refuse to drive properly. This is especially the case when going through ground containing boulders, which tend to deflect the drill head. To obviate this, the “ Keystone drill ” is fitted with a tool called a “ jar ” between the rock socket and the stem. It is like two links of a chain and when the bit is caught these two links come together with a shock, and jar the drill loose. As the value of the ground can only be determined by examining samples taken at regular distances, to be fixed by the nature of the stratum and the presence of the mineral, it is desirable that the tools bring up only such earth as is contained in the cylinder, and it is, therefore, essential for the tool to bore and the case to drive quite simultaneously and as nearly as possible at the same level. In calculating the values it is best to adopt the practice general in California, where the local engineers hold that the outside measurement of the case should be taken. They say that it is the displacement of the pipe and not the cubical contents that should be taken. In practice it is found that by taking the inside diameter of pipe the result is too high, and is never actually borne out by the results actually achieved by the dredges.

In case the reader should ever himself be actually prospecting with the drill, it should be mentioned that the operator must continually wash his hands as well as rinse down the rods with clean water. The effect of twisting or handling iron rods which are encrusted with sand or soil is to bring up very bad sores, and no prospector can do good work under these conditions.

The following is an extract from a paper read by F. W. Griffen, M.E., before the Californian Miners’ Association in 1903, and confirms many of the conclusions which have been arrived at by the writer during the last few years:

“ Whether or not a piece of ground is suitable for dredging is determined by physical conditions. To begin with, the deposit must be the result of a great flow of heavy gravel where the drainage area has been large and the ‘ feeders ’ good. The present creeks or streams which cut through a gravel deposit do not necessarily bear any relation to the original deposit. It must be practically flat lying, and the values must be disseminated over a wide area. You cannot dredge narrow, torrential portions of streams where large boulders abound. Where the bedrock is hard and the values are on that bedrock, the gold recovery of the dredge is materially reduced.

“ A piece of ground which fulfils the above conditions will bear investigation. Great care must be taken in prospecting, not only in the work itself, but also in placing the holes, and particularly in drawing conclusions from the results obtained. Prospect work is generally done with a drilling machine which sinks a hole 6 inches in diameter. The test by drill is fully as accurate as the test by shaft so far as the values obtained from the gravel prospected are concerned, but careful expert judgment must be used to reach an approximately accurate conclusion from the result of either drill or shaft. The reason for this is that one hole to ten acres is considered close prospecting. Therefore, if ten holes are sunk on a one hundred acre tract, and if the total value of these ten holes is divided by ten, and this result is taken for the true average value of the property, it will surely be misleading. The more holes you sink the nearer you come to the true value of a property. My deduction from a great number of cases in actual practice is that a dredge will produce from 60% to70 % of the arithmetical average value shown by drill-holes when the holes are placed approximately one to each ten acres of ground. This does not mean that the dredge will not save more than 70% of the values, but it does mean that the average value obtained from computing prospecting results as above set forth is erroneous by 30%. If a property shows an average value of 20 cents per cubic yard, then a dredging property has been proved. This is true only when the drilling has been carefully done, and proper allowances have been made —further, the property must be located in an accessible place, where power is cheap. The two factors of transportation and power must not be overlooked, and where they are high, the average value of the property must be proportionately high.”

In prospecting, it must be remembered that wherever the current of a river has been checked by any means gold will probably be found, and it is essential carefully to study anything that has tended to cause a change in the direction of the river. It will be found that wherever a stream has eroded a bank on one side it has simultaneously deposited shingle on the other side, the probability always being that the shingle thus redeposited is poorer than that in midstream, to which point the bulk of the gold has, ofcourse, a tendency to gravitate. Through having been washed of sands and practically reconcentrated, however, it will often be distinctly payable. Deposits of gold will often form on the quiescent shallow side of a stream and the main lead in midstream will not be of uniform richness.

As has been explained elsewhere, it is practically impossible to determine the former direction of the streams which have deposited the gold. Frequently the surface of the earth has been so changed in the meantime that it is hard to make definite deductions, and it is only after the river has actually been dredged that any data can be formulated. This brings us to a fact that cannot be too strongly insisted on. When all conditions are favourable very low grade gravel can be made to pay; in fact, even three to four grains per cubic yard gives a fair payable return, and very few bore-holes give a poorer prospect than that ; but it is impossible to compute the wealth of a river-bed by any other means than by actually dredging it. Some idea may be gained by testing exposed portions of the river-bed at low water, by bore-holes, by erecting wing-dams and thus exposing portions of the wash, or by divers; but such means cannot be relied upon as being even nearly accurate, the consequence being that considerable doubt must always exist as to the amount of success which will attend the primary operations of a dredge. As an instance of the way in which false data have been gathered, false conclusions arrived at, and exaggerations quoted, we need go no farther than the Klondyke. As many as thirty-eight sluicing and dredging concerns started operations there in 1897, and many more attempts were made to float companies. The country was reported upon as being suitable for all classes of hydraulic mining, whereas it was found in due time, and after millions had been squandered, that the gravels and nearly all the streams were for the greater part of the year both ice and snow-bound, that no roads for transport existed, and that many of the auriferous deposits were very patchy, and from almost every point of view quite impossible.

One of the best known and most reliable authorities on alluvial gold-getting in America recently gave me some interesting information from his own experiences. He says that check-holes do not necessarily serve as a good check upon the results obtained from holes previously drilled, though they are often useful as establishing the fact that the whole area of the ground is auriferous or otherwise. If one wants to check approximately the previous holes, the check-holes must, of course, be made very near those originally drilled. There is certainly a danger, however, of obtaining false results if the check-holes are placed only a few feet apart, as the ground may have been disturbed by boulders that have been pushed out of the way of the casing by the original drill. The first operator may have obtained much too flattering results by the running in of sand from the side of the casing, in which event the original hole might prove to be too high and the second hole too low in values to be anything like reliable. Whether a check-hole or a drill-hole is being put down, it can be safely assumed that the holes must be from five to ten feet distant from each other to be at all trustworthy.