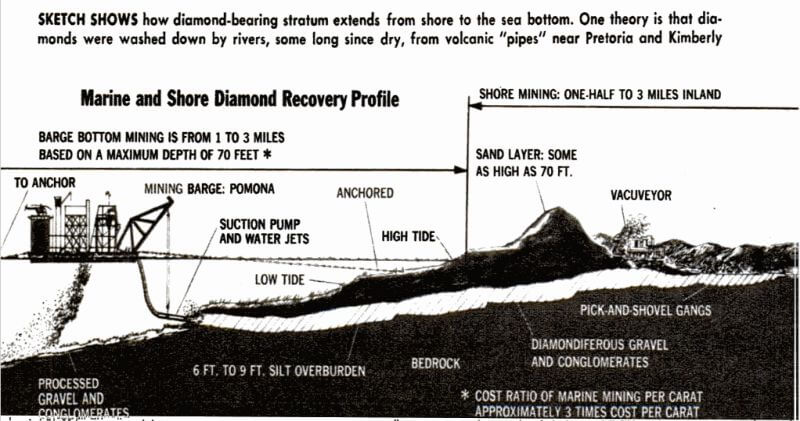

With regards to diamond dredges and dredging, the kings of the 1970s were Consolidated Diamond Mines and Marine Diamond Corp. both parts of the famous DeBeers company, control the coast of the Namib Desert and the waters and more important, the ocean floor and beaches of this treasure cheat of gems. So rich were the original finds that diamonds could be picked up in scene areas without any digging whatsoever.

That was in 1908 when the desert and the treacherous coast were the only guardians of this newly discovered wealth. The desert is still almost impassable, and the rough seas off a coast almost without harbors are more than fortune seekers can face. In recent years desert patrols and other security measures have further isolated this already inaccessible area.

By now the day had cleared. In place of the overcast, the sun shone fiercely through the plane’s canopy, while down below a heavy fog rolled in from the sea. So thick was the fog, as we came into land on the salt pan which served the camp at Hottentot’s Bay as a landing strip, that I could see no sign of the diamond dredge.

Slit-eyed against the salt’s blinding glare, we stumbled across to the big cargo helicopter which flew us to the shore party’s camp. There we sat drinking hot, strong tea and eating thick sandwiches while waiting for the fog to lift so the helicopter could take us to the dredge.

Miners are a rugged breed and warm hosts the world over, but I soon learned my first lesson. Although these men were full of tales of the coast and its diamonds, they sidestepped questions about company activities or details of the diamond dredge without giving anything away!

Piet Albertyn and the Beechcraft had to fly back to Oranjemund and on to Cape Town before nightfall, so our chances of getting out to the dredge lessened as the minutes ticked away.

But with less than an hour before time ran out the fog suddenly lifted. We scrambled for the helicopter and minutes later were hovering above the most unusual craft that ever floated on the South Atlantic.

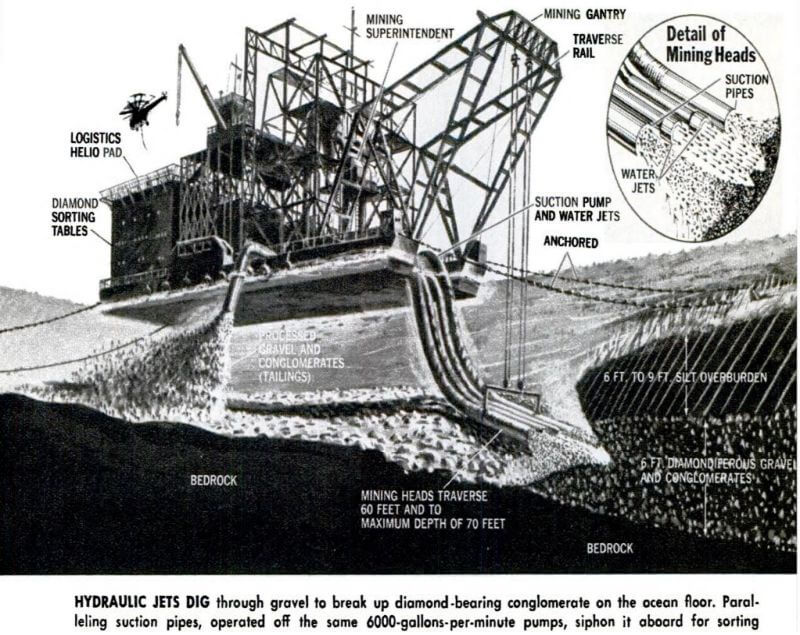

The Pomona was so huge and so crammed with derricks and gantries and gear that she looked like a vast barge carrying the Queensboro Bridge down New York’s East River.

We landed atop the living quarters at the sharply pointed end of the monster, which turned out, surprisingly, to be its stern. Just as surprisingly, the bows, pointing shoreward and mounted with towering girder-work carrying the mining and suction heads were blunt and square.

I caught the name “Kruger” and a big man was shaking me by the hand and welcoming me onboard. But such was the racket of the helicopter engine and the diamond dredge in action that I watched his lips moving without hearing a word.

Besides, I was learning one of the dredge’s secrets without even asking for it, for, as we flew onto the dredge, its mining heads were being lowered beneath the water. Now I watched them disappear slowly into the sea.

In Cape Town I had asked in vain for technical details of those heads. Did they cut with rotary teeth or with blades? Now, in the 30 or 40 seconds in which they had been visible, I could see they were armed with high-powered hydraulic jets to break up conglomerates on the sea bottom, while twin steel pipes sucked the diamond-rich debris onboard for processing.

Immediately behind the jet heads, the pipes were rigid for some 30 feet, then flexible from there to back onboard to accommodate changes in depth and angle of cutting.

Mining was controlled by a single man sitting at a console in a centrally located observation post. There were two such dredging superintendents. Each worked a 12-hour shift.

Each shift had a port and starboard winchman, who moved the barge in an exact pattern between her mooring buoys. Four great anchors, parallel to the shore, held the bow. Another four, to seaward, held the stern into the prevailing wind sweeping in across the South Atlantic.

Each winch-drum held 3500 feet of heavy cable. As the dredging superintendent swept the jet heads from side to side in a 60-foot arc, the winchmen inched the Pomona forward to keep the jets against the work-face.

The jets cut a trench some 70 meters long and 20 meters wide, before the heads were raised and the dredge winched back and seaward to start again. The dredge was then winched sideways 60 feet, heads lowered and a new trench begun. Three Amsco dredge-pumps handling 6000 gallons per minute gave power to break up the conglomerates and siphon them onboard.

The first layer uncovered is usually silt; the second, gravel mixed with shell and fine silt. Sometimes there is a third layer of gravel mixed with clay. It is in the gravel and conglomerates that the diamonds are found.

General sediment depth is 8 to 9 feet. The diamond-bearing gravels vary in thickness up to 30 feet or more. Those being worked were 6 to 9 feet thick.

Securely trapped in her network of mooring lines, the Pomona rose and fell as the long rollers swept shoreward beneath her. The jet heads were suspended in a system of counterweights which automatically kept the clusters of hydraulic jets positioned correctly.

Weather is the big enemy, salt corrosion second, isolation and loneliness third.

As mining superintendent Kruger and I carried on a shouted conversation he continually kept his eye on the weather out to sea. Although the Pomona had already ridden out 35-foot waves, all mining activities stop at the first sign of bad weather.

Waves up to 40 feet had been recorded when an earlier barge was torn from its moorings and swept ashore. The Pomona carried twin 1000-hp auxiliaries, and a powerful tug stood by night and day to pass her a towline if winds reached gale force.