As mentioned before, in the last chapter, any one who searches for useful minerals is chiefly attracted by their colour; the lustre, and perhaps streak, may assist him in the determination of their nature. Still, doubts may suggest further investigation. The hardness and the specific gravity may guide him, though it must be confessed, in the case of small minerals, it is no easy matter to accurately find out the latter. Even then recourse may have to be had to what in many cases is really the most satisfactory way of solving the question, namely, to tests by means of the blowpipe or by chemicals. In the following pages is given an account of the principal useful ores—comparatively few in number— including a description of their characteristics and behaviour in the blowpipe flames and with certain chemicals, also of the country rock in which the lodes or deposits occur.

As a general rule, the ordinary prospector concentrates his attention to the discovery of the precious metals, gold and silver (usually the former). Perhaps he keeps a look- out for lead and copper ores, but very seldom (even when in a granite country) thinks about searching the streams for tinstone or the hills for tin-bearing lodes. He may pass by, or even handle and throw aside, such unmetallic-like minerals as some of the silicates, carbonates, chlorides, &c., simply because of their lightness of weight, or because they do not come up to his notions about what a metal-bearing rock should be. He may even discard some of the heavy minerals on account of their nature being disguised by the presence of iron oxide, which may give them the appearance of an iron ore. Hence the desirability of examining carefully all sorts of minerals and submitting them to tests.

Although in this chapter many of the different metallic compounds are described, it would be well if the prospector made himself especially well acquainted with the appearance of the various oxides, and in a lesser degree with the carbonates, chlorides. The sulphides which are found deep down a lode become chiefly converted to oxides on the surface. Take, for instance, a lode in which copper pyrites and iron pyrites exist several fathoms down. On the outcrop there would probably be the rusty colour due to iron oxide; and black oxide (perhaps the red) of copper, and also the green or bluish stain of carbonate of copper might be distinctly noticed. Still, whether the prospector comes across oxides, carbonates, chlorides, sulphides, or metal in the native state, recourse to the following pages may, per- chance, help him to solve the question as to what the true nature of the particular mineral is.

ALUMINIUM

This metal is not found in the native state, but in combination with silica, oxygen, fluorine. Corundum, sapphire, and ruby are nearly pure alumina (oxide of aluminium). Emery is a more impure variety. The silicate is very abundant and is a constituent of the older rocks, of all clays. The presence of alumina is known by heating the substance in the B.F., then moistening it with nitrate of cobalt solution and again heating. A blue, lustreless colour will indicate the presence of alumina, thus distinguishing it from magnesia in a mineral.

The principal ores besides corundum (H. 9), found in great quantity in crystalline rocks in America, and from which aluminium is extracted, are—

Bauxite

Of various colours. Bauxite is sometimes made up of concretionary grains. Also as clay (sometimes coloured by iron oxide).

S.G.—2·55.

Contains sometimes more than 50 per cent, of alumina (or more than one-third aluminium), the rest being sesqui- oxide of iron, silica (in small quantity), and water. Is soluble in sulphuric acid.

Cryolite

A semi-transparent, brittle mineral.

Colour—whitish yellow, reddish, or black.

H.—2·5 ; S.G.—3.

Is a double fluoride of aluminium and sodium, and contains sometimes 13 per cent. of aluminium. Easily fusible in candle flame.

Beauxite is chiefly found near Arles, in the south of France. A rather similar clay has been found in Ireland.

Cryolite is obtained in Greenland (in gneiss), also in America.

Aluminium is of a white colour, easily polished, adapted for casting into moulds, does not become tarnished on exposure to the atmosphere, and hence is suitable for very many purposes.

ANTIMONY

The metal is usually found combined with sulphur, arsenic, or sulphur and lead. If a mineral be supposed to contain antimony in any form, the presence of the metal may be known by treating the specimen with carbonate of soda on charcoal in the R.F. of the blowpipe, when, if it be present, a bluish white incrustation is formed, which (being volatile) disappears when exposed to the O.F. and R.F.; in the latter case with green coloration. The bead is white and brittle.

To confirm:—Scrape the incrustation off and treat with hydrochloric acid and zinc on platinum foil. A film of antimony will be left on the latter. If a piece of ore containing antimony be heated in an iron spoon, white fumes will rise and coat the rim. The behaviour of antimony with borax or platinum wire before the blowpipe flames is, when cold, in O.F. = colourless, in R.F. = colourless to grey.

Combined with lead, or bismuth, or copper, other tests have to be resorted to. Antimony is a most undesirable metal to be associated with other metallic compounds in a vein, as it interferes with the ordinary smelting processes.

Sulphide of Antimony (grey antimony)

The ore from which the antimony is extracted:

- Crystallization—right rhombic prisms.

- Colour—lead grey.

- Streak—lead grey and blackish.

- Lustre—shining and metallic.

- Structure—brittle : thin laminae slightly flexible.

- H.—2 ; S.G.—4·5 to 4·7.

- Composition per cent.—antimony, 73; sulphur, 27.

Fuses in the flame of a candle

Before B. flame and on charcoal yields white fumes with odour of sulphur. When pure, is soluble in hydrochloric acid. The oxide—yellow, white, grey, or brown—is sometimes found on the outcrop of a sulphide-bearing lode. Can be distinguished from an ore of manganese, like in appearance, by its being easily fused and its diagonal cleavage.

There are about ten varieties of this last ore, the streaks of which vary ; all the ores, however, are soft, and can be scratched by the finger nail. Grey antimony occurs with ores of silver, lead, zinc, or iron, &c., and is often associated with heavy spar and quartz. Found in metamorphic and igneous rocks. If antimony sulphide is heated in a glass tube closed at one end, a sublimate, black when hot, reddish-brown when cold, is formed near the test-piece.

BISMUTH

Found chiefly in the native state, but also in combination with sulphur, oxygen, tellurium, carbonic acid, &c. It yields a yellow incrustation in the O.F. of the blowpipe.

The oxide, sulphide, arsenide, combined sometimes with copper, lead, vary in colour, hardness, and specific gravity. Bismuth glance, containing 81 per cent, of the metal, is usually of a lead-grey colour. When heated in a closed tube yields a sulphur sublimate. On charcoal before the B.F. sputters and deposits a yellow incrustation leaving metallic bismuth. Oxide and carbonate of bismuth (generally of a yellowish, though sometimes grey, greenish white, &c.) is often found at the surface of a bismuth-bearing lode. In Wales and elsewhere bismuth sulphide is sometimes found in gold-bearing ore.

CHROMIUM

The oxide is chiefly found with iron, as chrome iron.

Colour—brownish black.

Lustre—submetallic.

H.—5·5 ; S.G.—4·5.

Before the B.F. yields a green bead with borax. Chromate of lead is rarely found. Occasionally an emerald green incrustation is found on chrome iron ore. Chrome ochre is of a yellowish green colour. Chrome iron is frequently found in a serpentine-rock country.

Chromium compounds are often associated with nickel and cobalt ores.

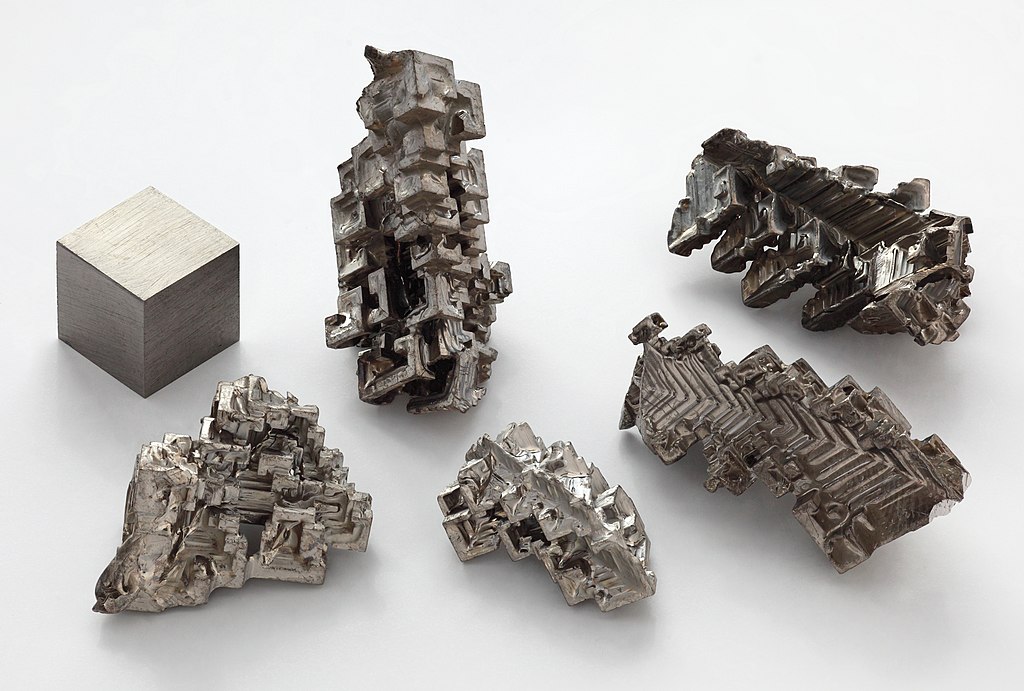

TYPES OF COBALT MINERALS

Compounds of cobalt, when heated on charcoal before the B.F., yield whitish metallic spangles, which can be attracted by a magnet. The metal moistened on paper with nitric acid gives a red solution, which with hydrochloric acid affords a green stain on drying.

Treated with borax in either B.F. it yields a deep blue bead. Before testing, metallic compounds should be roasted, to drive off volatile matter.

Tin White Cobalt

Crystallization — octahedral, cubical, and dodecahedral, &c.

Breaks with uneven and granular fracture.

Colour—tin white and greyish.

Streak—greyish black.

H.—5·3; S.G.—6·4 to 7·2.

Composition—cobalt and arsenic.

Before the blowpipe it colours borax and other fluxes blue. Affords pink solution with nitric acid.

Earthy Oxide

Usually massive.

Colour—blue black or black.

H.—1 to 1·5 ; S.G.—2·2 to 2·6.

Composition—oxides of cobalt and manganese.

Cobalt Bloom

Lustre—pearly.

Colour — peach red, crimson; sometimes grey or greenish.

Streak—paler ; powder-lavender.

Composition per cent.—oxide of cobalt, 37·6; the remainder, arsenic and water.

Gives off arsenical odour when heated. Behaviour with fluxes in the B.F. same as other cobalt ores. In Great Britain cobalt ore is found in cavities in limestone of the carboniferous age. In Norway and other countries a variety of tin white cobalt is found in gneissie and primitive rocks. In Germany deposits of cobalt are found in limestone over copper slates. Cobalt and nickel ores are often met with in the same lode.

TYPES OF COPPER MINERALS

If a specimen is supposed to contain copper, it should be examined either by means of the blowpipe or chemicals. With carbonate of soda on charcoal before the B.F., nearly any copper ore is reduced and a globule of metallic copper obtained. Heated with borax or microsmic salt in the O.F. there results a green bead when hot, a blue one when cold. Most copper compounds, when heated in the inner flame, impart a green colour to the outer one. Copper compounds are, for the most part, soluble in nitric acid. If a piece of polished iron or the bright point of a penknife be dipped into the acid solution, it will be slightly coated with metallic copper if any exist in the ore. Ammonia added to an acid solution affords a green colour, and, in excess, a blue one. Many copper minerals can be dissolved in citric acid, some in cold, others in a boiling solution, and afford a greenish colour. A penknife blade (clean; placed in the solution is covered with a copper film. Some, such as copper pyrites, may be dissolved in a boiling solution of citric acid and nitrate of soda. In the absence of a blowpipe or chemical apparatus, the presence of copper in a substance may be detected in this way:- First, roast the mineral and drop it, when hot, into some grease and expose it to the heat of a flame, which will show a green colour if copper exists. Or, if the mineral be well powdered, mixed with some fat and salt, and placed in the fire, the presence of copper will be known by the blue or green colour. If the powdered mineral be mixed with a little charcoal and roasted for an hour, and then vinegar be poured on it and allowed to remain for a day or so, copper will produce a blue colour, afterwards becoming green.

In a copper-bearing lode the black oxide, sometimes red oxide and green carbonate, may be noticed in the cavities of the surface quartz.

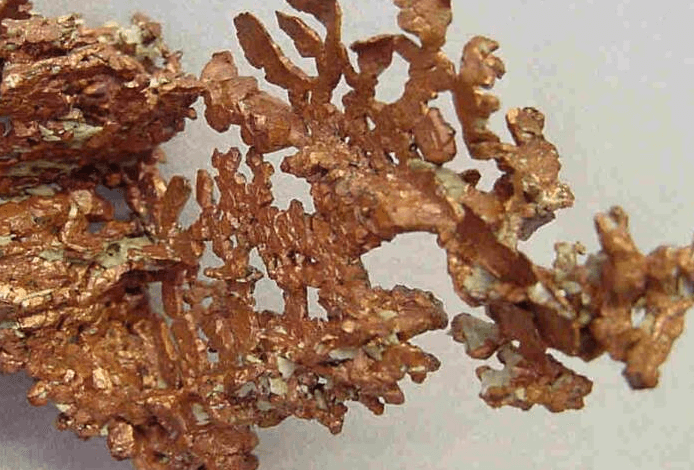

Native Copper

Native copper is found in treelike, mosslike, thread like shapes, in octahedral crystals, grains, &c.

Colour—copper red.

Is ductile and malleable.

H.—2·5 to 3 ; S.G.—8·5 to 8·9.

Can be tested by the blowpipe or chemicals like other copper ores. Usually carries silver. Found chiefly in North and South America, also in Cornwall, Wales.

Copper Glance (vitreous copper ore)

Crystallization—rhombic prisms. Is slightly sectile.

Colour—blackish grey, tarnishing to blue or green.

Streak—blackish grey, sometimes shining.

H.—2·5 to 3; S.G-.5·5 to 5·8.

Composition per cent.— sulphur, 20·6 ; copper, 77·2 : iron, 1·5.

Before the blowpipe gives off sulphur fumes, fuses easily in the outer flame, and boils, leaving a globule of copper. Is fusible in a candle flame. Is rather like sulphide of silver, but the button left after exposure to B.F. shows the difference. If the mineral be dissolved in nitric acid, and the point of a penknife be placed in it, a slight copper coating will be formed if the metal is present, whereas, if a piece of bright copper be placed in it, a slight coating of silver will be formed if silver be present.

Copper Pyrites (chalcopyrite)

Crystallization—tetrahedral, also massive.

Colour — brass yellow, sometimes tarnished and indecent.

Streak—greenish black and nonmetallic.

H.—3·5 to 4 ; S.G.—4·15.

Composition per cent.—sulphur, 34·9; copper, 34·6; iron, 30·5.

In a glass tube closed at one end it decrepitates, and a sulphur sublimate is left.

Before the B.F., it fuses to a metallic globule. If fused with borax, metallic copper is the result. Tested in acid, like other copper ores. Is sometimes mistaken for gold, iron pyrites, or tin pyrites; but it crumbles when cut, whereas gold can be cut in slices. Is of a deeper colour than iron pyrites, and yields easily to the knife, nor does it strike fire like iron pyrites. It may be distinguished from tin pyrites by the blowpipe and other tests. If the ore be hard and of a pale yellow colour, it is considered to be poor in copper.

Variegated copper pyrites (containing 60 per cent, of copper) is of a pale reddish yellow colour.

Grey Copper (tetrahedrite)

When containing silver, Fahlerz.

Crystallization—tetrahedral.

Structure—brittle.

Colour—between steel grey and iron black, sometimes brownish.

Streak—between steel grey and iron black, sometimes brownish.

H. —3 to 4; S.G.—4·75 to 5·1.

Composition per cent.—copper, 38·6 ; sulphur, 26·3 ; antimony and arsenic, zine, iron, silver, &c.

It sometimes contains 30 per cent. of silver in place of part of the copper. After roasting, yields a globule of copper before the B.F. When powdered and dissolved in nitric acid, the solution is brownish green. The ore can be distinguished from any silver ore by the blowpipe and chemical tests. The darker the colour the less arsenic in it.

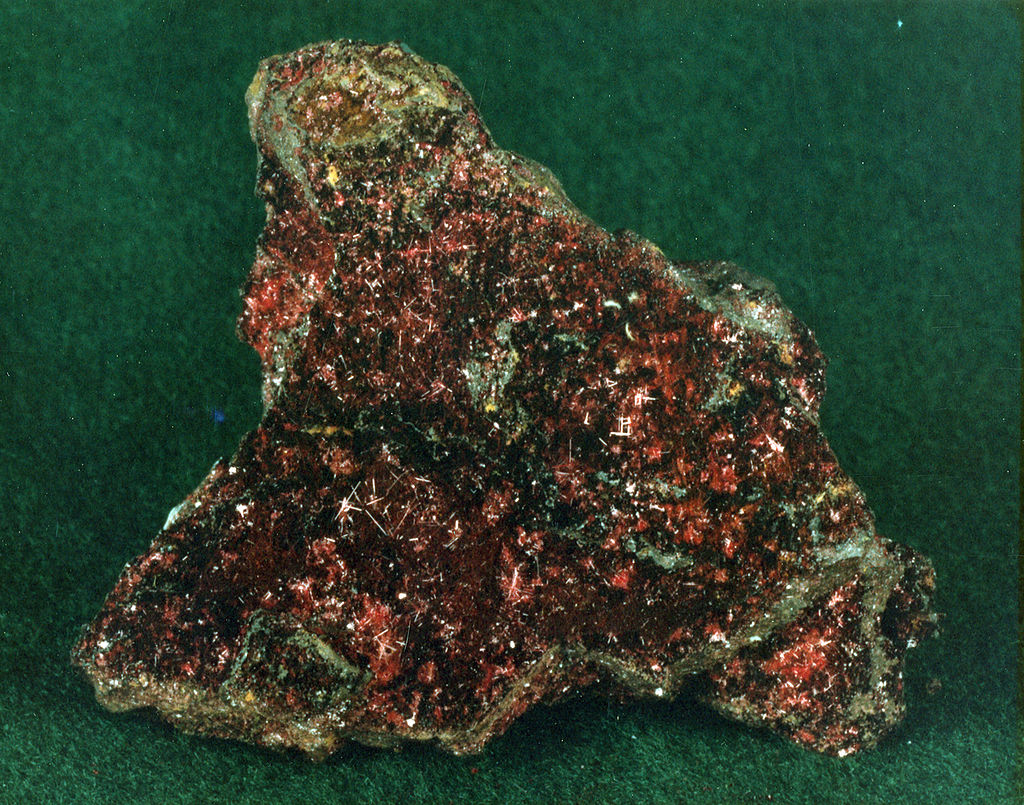

Red Copper Ore (ruby copper)

Found massive, earthy, granular.

Crystallization—octahedral, and dodecahedral.

Structure—brittle.

Lustre—adamantine, or submetallic. Is subtransparent or nearly opaque. Detached crystals look rather like spinel rubies.

Colour—deep red, ruby colour, though it is often iron grey on the surface.

Streak—always brownish red.

H. —3·5 to 4 ; S.G.—6.

Composition per cent.—copper, 88·78 ; the remainder oxygen.

Heated in a tube closed at one end, it darkens. Yields globule of copper before the blowpipe. Dissolves in nitric acid. Soluble in ammonia : solution eventually azure blue.

Black Oxide of Copper

Usually found on the surface, due to the decomposition of a sulphide or other copper ore. Black copper at the top of a lode may indicate some other copper compound deeper down. If the dusty powder be rubbed between the fingers and dropped on a flame, the latter will be coloured green. Soluble in ammonia : solution azure blue.

Silicate of Copper

Usually as an incrustation, massive, &c.

Colour—bright green and bluish green.

H. —2·3 ; S.G.—2 to 2·3.

Contains 40 to 50 per cent, of oxide of copper.

Is rather like malachite in colour, but when dissolved in nitric acid a precipitate is left, whereas malachite is quite dissolved.

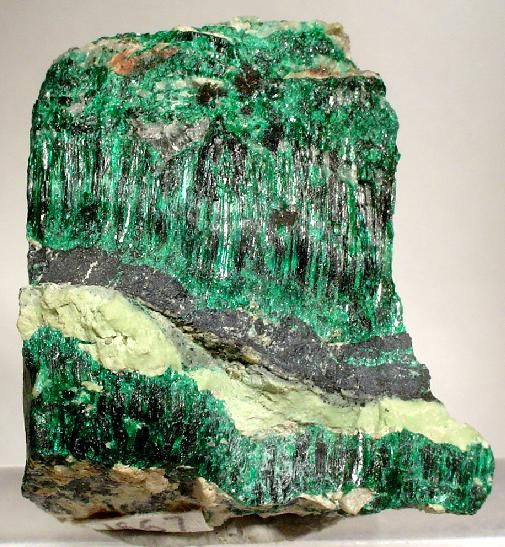

Malachite (green carbonate of copper)

Found in botryoidal or stalactitic masses, and as an; incrustation, &c.

Structure—fibrous.

Nearly opaque.

Colour—emerald green.

Streak—a paler green than the colour.

H. —3·5 to 4 ; S.G. 3·6 to 4.

Contains about 57 per cent, of copper.

Before the blowpipe it becomes blackish. With borax before the B.F. it forms a green globule, and eventually yields a copper bead.

Completely dissolves in nitric acid, and so differs from other ores of a similar appearance.

The blue carbonate is very like the above; but its crystallization is a rhombic prism, and its streak bluish.

It is impossible to enumerate more than a few of the localities where copper ore is found and its manner of occurrence. It occurs in rocks of every age and in both lodes and deposits. The usual ore in a copper lode is pyrites, which is decomposed into black oxide at the surface. In Cornwall the copper lodes, which generally run east and west, are more productive in the slates than the granites. The New Red Sandstone of Cheshire and Shropshire contains certain deposits of copper, chiefly malachite : and in the Carboniferous Limestone of Shropshire are also deposits of the same ore as well as pyrites. Copper pyrites veins traverse green slates and porphyritic rocks in the north of England. Not to mention the variety of lodes which run through rocks of various age of North America, the following are a few examples of the position of certain deposits.

In the Eastern States there are deposits in the New Red Sandstone, also in the Carboniferous Limestone and Silurian rocks. In the Lake Superior district, where so much native copper is found, deposits occur in sandstones and shales, underlying greenstone, &c. There are also lodes running through the various strata. Deposits of ruby copper ore occur in Arizona between quartzose and hornblendic rocks and limestone. Lodes and deposits in Chili are worked in hornblendic and felspathic quartz rocks. The celebrated Burra Burra mine in Australia, from which splendid lumps of malachite are familiar objects in museums, consists of an immense irregular deposit of malachite and other copper ores in limestone and harder rocks, as well as in the soil. Copper deposits occur elsewhere in schistose, hornblendic, quartzose rocks, &c., and pyrites-bearing lodes through rocks of various ages.

Copper sulphides (with or without antimony, arsenic) often occur in gold and silver-bearing lodes; and, therefore, though neither free gold nor a silver compound may be noticed on the outcrop, assays should certainly be made.

General remarks.—Aluminium; bauxite; cryolite.—Antimony; sulphide. — Bismuth. — Chromium ; oxide. — Cobalt; tin white ; earthy oxide.—Copper; native ; glance ; pyrites; grey; ruby; black oxide ; silicate ; malachite.—Gold ; detection of and distinguishing tests ; peculiarities ; panning out; mechanical assay ; sluicing ; native gold, &c.—Iron ; pyrites ; magnetic pyrites ; arsenical pyrites; haematite ; magnetic iron ore ; brown iron ore ; franklinite; vivianite; copperas ; spathic ore.—Lead ; galena ; carbonate; pyromorphite ; chromate ; sulphate ; rough method for obtaining lead from galena.—Manganese; black oxide, wad, &c.—Mercury; native ; cinnabar ; chloride ; selenide; to obtain metal from ore.—Nickel; kupfernickel; white; emerald; hydrated silicate.—Platinum; native.—Silver; native ; brittle ore; glance ; horn silver; ruby ore; silver in carbonate of lead.—Tin; tinstone ; bellmetal ore.—Zinc ; calamine ; silicate ; red zinc ore.