Table of Contents

Among smelters generally, the prevailing opinion is that in a slag which is either extremely acidic or extremely basic in character there is a greater or less loss in silver values. Some assayers have the same notion. Among them also there is the belief that the use of borax in assaying causes low results for the silver content. On the other hand, the majority of assayers appear to regard the use of borax as removing at once all of the difficulties which in any way arise from imperfect fluxing in the crucible. From experience, the inclination is to regard many charges, and slags, which by the assayer are ordinarily called good, especially when they contain much borax, i. e., 0.5 A-T., or more, as not, in case of moderately high-grade ores, checking well with one another. The usual methods of assay of ores running high in copper and sulphur are also very unsatisfactory.

The series of determinations, of which the single silver-ore here considered in detail is a type, had for its immediate objects the experimental proving of the effects upon the silver-yield of an excess of each of the fluxes ordinarily used in the crucible of the assay laboratory, and of showing exactly what type of charge gives the best results on an ore which is high in copper and sulphur, and which at the same time is a typical roasting-ore.

In the ore under consideration the silver content assaying was already known to be high. By experimentation it was determined:

- how acidic a charge could be run;

- how basic a charge could be run;

- how large an amount of borax could be used in a charge;

- how the normal charge for the kind of ore would behave; and

- how the use of an excess of litharge would affect the results.

This ore was much more difficult to handle than many of those found in the region. The large excess of niter, KNO3, which it was necessary to use was checked against the dead-roasted ore. In each series the attempt was made to get five results that would check within 1 in 100; and to take the mean of these best checks as the normal for the charge used. A concentration-test was made on the ore, and the reducing- power and value of the concentrates determined in order to find whether or not the value, the sulphur, the weight of the ore, and the weight of the concentrates, had any definite relations to one another. It is to be noted that whenever the word “borax” is mentioned, the variety known as “borax glass” is referred to, and all crucibles received a cover of 10 g. of borax before fusion; that all buttons of the same ore were worked as nearly as possible under the same conditions, and all were scorified with the same weight of test-lead; and that all buttons were cupelled so as to obtain “ feathers.”

Preparation of Samples & Chemical Analyses

In preparing the ore 32 lb. was pulped and put through a 100-mesh sieve, and then mixed by rolling on oil-cloth and sifting through a coarse sieve. The separated scales gave a bead of 83.4 mg. of silver and a trace of gold. In all of the assays this ore gave only a trace of gold. By panning 100 g. of ore, 44.9 g. of concentrates, mainly sulphides, were obtained.

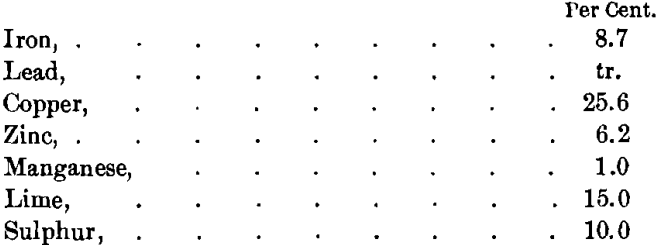

A part chemical analysis of the ore-sample ready for slagging gave :

Reducing-Power of the Ore

In determining the reducing-power of the ore, the charge, with borax cover, was as follows : Ore, 2.00 g.; PbO, 1 A-T.; NaHCO3, 0.75 A-T. The lead-button obtained weighed 7.105 g., the reducing-power of which was 3.6, the oxidizing- power of the niter being 3; therefore { [(7.105 ÷ 2) 14.5] — 15.0 }— 3.0 = 12.0 g. of niter per charge. This charge of niter, KNO3, is excessive, but there appears to be no other way of handling this ore easily. If properly run, the excess of niter is not so deleterious in its effects as those of roasting, which is the only other practical method.

Assay of Dead-Roasted Silver Ore

In the case of the dead-roasted ore the charge, with borax cover, was: Ore, 0.5; PbO, 1.5; NaHCO3, 0.75; SiO2, 0.2 A-T.; and argols 2 g. There was secured a good slag which poured cleanly. The buttons were hard and coppery; these were scorified with 20 g. of test-lead. The cupels displayed a coppery tint. The first bead weighed 103.06 mg.; the second bead, 103.90 mg.; the mean being 103.43 mg. of silver. Comparing this with the values obtained later, it shows that a dead roast is not so reliable as some other methods; besides, it involves much more labor.

Dead-Roasted Silver Concentrates

The reducing-power of the concentrates was 5.2, showing that the sulphur concentrated nearly as fast as the ore.

With the dead-roasted concentrates the charge, with borax cover, was: Ore, 0.5; PbO, 1.5; NaHCO3, 0.75; SiO2, 0.2 A-T.; and argols, 2 g. The slag was good and the pour clean. Buttons hard, clean, and copper-colored; these were scorified with 40 g. of test-lead. The cupels showed copper-stain. The silver bead weighed 114.75 mg. These results indicate that the concentration of the values is not in proportion to the concentration of the bulk or of the sulphur; hence the ore is not a good concentrating-ore.

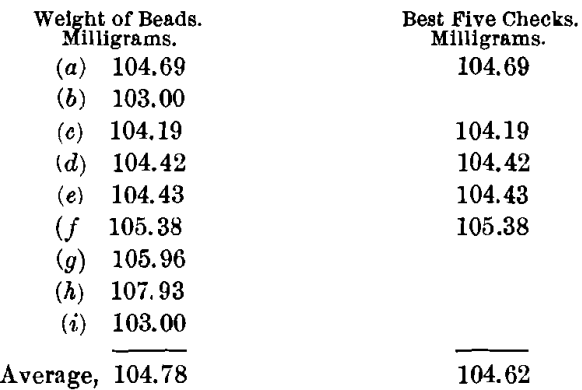

Acidic Slags

The charge for obtaining the most acidic slag, using a borax cover, was: Ore, 0.5; PbO, 1; NaHCO3, 0.75; SiO2, 0.40 A-T.; and KNO3, 12 g. By experiment, this is the most acid flux that it is possible to run on this ore. The charge required a long time and a very high temperature to fuse. The slag was thick, viscous, and poured poorly yet cleanly; when cold, it was reddish brown in color and stony in appearance, with distinct indications of copper oxide. The buttons were hard, matte-like, and coppery. In no sense was either slag or button good.

The buttons were scorified with 40 g. of test-lead and 0.1 g. of borax, and then rescorified without more lead. The scorifiers were badly corroded. The buttons were now small, clean, soft and malleable. Their weights were made up to 15 g. with sheet-lead, and they were then cupelled. The cupels were deeply stained with copper.

The highest value was 107.93, or a difference of 3.31 mg. from the mean of the best five. The lowest value was 103, or a difference of 1.62 mg. from the mean of the best five. Too wide a variation in the results is shown for them to be satisfactory, especially taking into consideration the high heat, poor pour, long period of fusion, and double scorification.

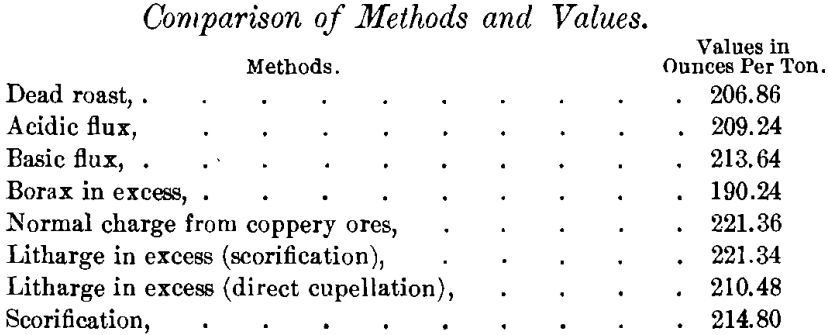

By this method the ore gives a silver-content of 209.24 oz. per ton.

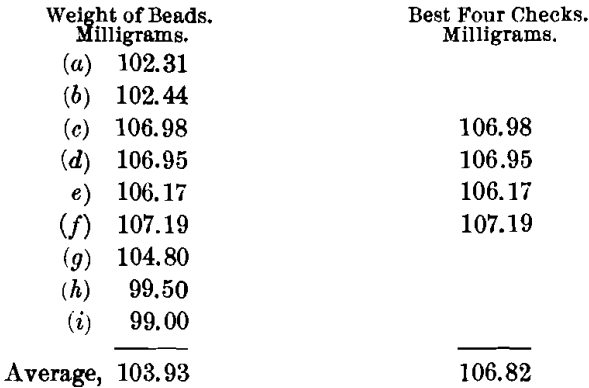

Basic Slags

The charge, using a borax cover, for obtaining the most basic slag was: Ore, 0.5; PbO, 1; NaHCO3, 1.5 A-T.; and KNO3, 12 g. This was found to be the most basic flux that could be run even approximately satisfactorily. A very slow and long fusion was required. The pour was clean and the slag moderately liquid. The cold slag was brittle, granular, stony, and gray to buff in color, with some indications of copper oxide. Buttons were hard, clean, and malleable, but extremely coppery. The buttons were scorified with 40 g. of test-lead and 0.1 g. of borax, then rescorified without further addition of test-lead. The weight was made up to 15 g. with sheet-lead, and then they were cupelled. The cupels showed strong copper-staining.

The highest value is 107.19, or a difference of 0.37 from the mean of the best four, which is a very good result. The lowest value is 99, or a difference of 7.82 from the mean of the best four, which is a very poor result. This flux shows a higher best mean and a lower general mean than the acidic flux. The variations are also greater and the slag nearly as difficult to run. The same amount of scorification is required as in the case of the acidic charge, but the clean buttons are obtained at the first fusion. Since this flux is quite as unsatisfactory as the acidic flux, some intermediate or special charge must be found for this type.

The silver-value by this method is 213.64 oz. per ton.

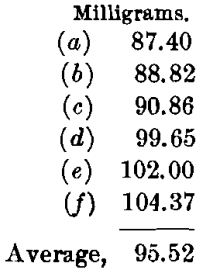

Use of Borax in Excess

The charge, with borax cover, was: Ore, 0.5; PbO, 1; NaHCO3, 0.75; Na3B4O7, 1 A-T.; and KNO3, 12 g. This charge required long, slow fusion at a medium temperature, but needed constant watching and much salting-down to prevent boiling over. The pour was good and the slag quite liquid. The cold slag was of dark purplish color and stony in appearance. The buttons were very hard and brittle and were composed mainly of matte; these were scorified with 40 g. of test-lead and 0.1 g. of borax, and rescorified with an addition of 20 g. of test-lead. The cupels showed strong copper-stains. The beads weighed as follows:

The highest value is 104.37, or a difference of 8.85 from the mean. The lowest value is 87.40, or a difference of 8.12 from the mean. These results are very unsatisfactory, and indicate clearly the disadvantages of using a large excess of borax.

The silver-values by this method are only 190.24 oz. per ton.

Normal Charge for Coppery Ore

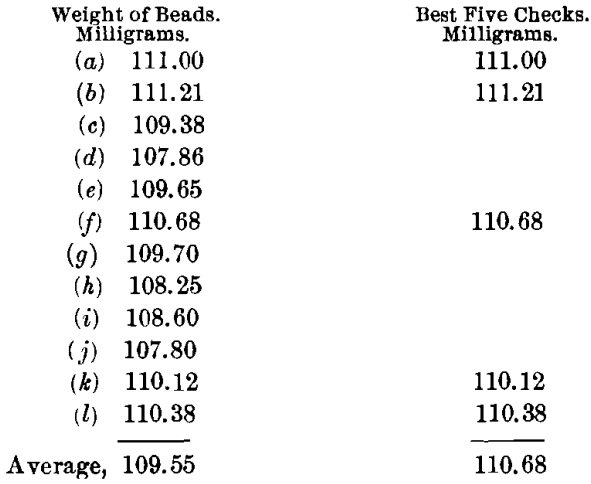

In making up the normal charge for a coppery ore the following amounts were used, with borax cover : Ore, 0.5; PbO, 1.5; NaHCO3, 0.75 A-T.; and KNO3, 12 g. There was quick fusion at a moderate heat and a clean pour. The cold slag was stony in character, and yellowish red in color. The buttons were clean, hard, and coppery; they would not cupel directly; hence, they were scorified with 40 g. of test-lead and 0.1 g. of borax. The cupels indicated the presence of copper.

It is to be noted that of these results (c), (e), (g), (h), and (i) give a mean that checks as well within itself as the ones selected, being 109.51. The highest value is 111.21, or a difference of 0.53 from the mean of the best five. The lowest value is 107.80, or a difference of 2.48 from the mean of the best five. Although not entirely satisfactory, these results are much better than in the case of any of the preceding methods, especially when the quick, easy fusion and the clean buttons at the first fusion are considered. The results also show higher values.

The silver in the ore, according to this method, amounts to 221.36 oz. per ton.

Effects of Litharge used in Excess

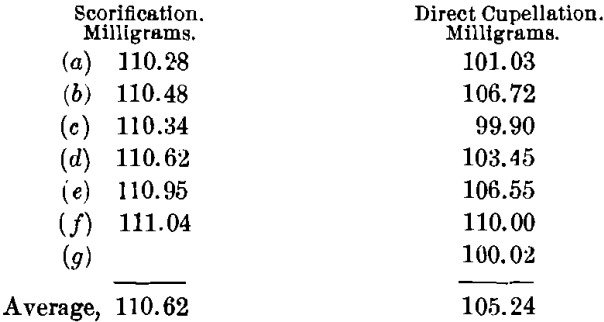

With an excess of lead oxide the following charge was used, with a borax cover: Ore, 0.5; PbO, 3; NaHCO3, 0.75 A-T.; and KNO3, 12 g. The fusion was of short duration at a low temperature. Slag was stony in character and of yellowish- brown color. Buttons were clean, soft, malleable, and cupelled direct; these were scorified with 40 g. of test-lead and 0.1 g. of borax. The cupels were coppery. The beads weighed :

All of the scorified buttons came within the limits of 1 in 100, with high silver-yield. The highest value, 111.04, shows a difference of only 0.42 from the mean. The lowest value, 110.28, differs from the mean by only 0.34. This excellent checking commends the use of a large excess of litharge in the assay of coppery ores.

The silver-value of the ore by this method is 221.34 oz. per ton. This is 0.02 oz. less than by the method of the normal charge for coppery ores; but the check is so much better than the last mentioned that it is far superior, while the procedure is no longer and is not more difficult. The attempt to cupel directly gave results varying from 99.90 to 110.02, hence this method is not to be recommended. The value indicated by direct cupellation is 210.46 oz. per ton.

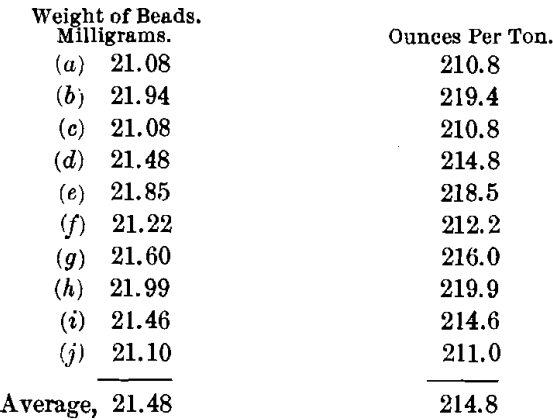

Special Scorification-Tests

In order to determine the effects of the presence of the large amounts of niter used, a series of scorifications were run. The charge was: Ore, 0.1; Pb, 50; SiO2, 1; Na2B4O7, 0.5 g. These tests gave good slags and buttons that cupelled directly with only a slight copper-color on the cupel. The values were as follows:

These results show a lower general mean and a much less satisfactory check than either by the normal charge method or by the use of an excess of litharge. It has the further disadvantage of necessitating the working on a very small quantity of the ore. Besides, it requires as much time as either of the other methods, and hence is not so advantageous.

Significance of Assay Results

From the above tabulation of results it may be inferred that:

- A dead-roast is not so satisfactory or so accurate as a run with a large excess of niter or a scorification on a charge of 0.1 A-T., or more; moreover, the roasting involves much more labor.

- An excess of borax causes low value-determinations, especially in the presence of large amounts of sulphur, copper, iron, or other matte-forming substances. Although it is not believed that any one with experience at the furnace would hesitate to recommend borax, if properly used, the use of large amounts approaching 1 A-T. must give low results on all types of ores.

- An excessively acid flux fuses with great difficulty and gives buttons that are hard to handle and that are frequently lost in cleaning. Further, when the ores contain matte-forming materials, the value-determinations are low; but when very little or no matte material is present, these results are not only much too high but quite difficult to obtain.

- A very basic flux is open to all of the objections which can be raised against the acidic flux, and in about the same ratio as regards checking-figures. However, in coppery ores, the loss is not quite so great, but in zinciferous ores the results are too high. Neither method is practical; and both give variant results most of the time, unless great care be taken in the handling of the lead-buttons.

- Ores high in copper cannot be run by any crucible method without scorifying the lead-buttons.

- Direct scorification on high-grade copper-bearing ores does not check as well or give as high values as a combination of the crucible and scorification-methods; besides, it is not a process which is more speedy.

- The normal or usual charge for coppery ores gives as high results as any method on this type of ore, but its checking is not of the best as compared with that in which a large excess of litharge is used. The normal charge for ores containing some zinc gives slightly lower values than in cases in which an excess of litharge is used, but still the checks are good for the grade of ore.

- For ores high in copper or carrying some zinc, a large excess of litharge in the charge greatly improves the buttons and renders them easily handled. Furthermore, this decreases the time and temperature of the fusion, and gives buttons that check well, with very close to actual valuations for the silver-content of the ore. The method is quick, easy, and accurate.

For a period of several years, and in a large number of cases, the Metallurgical Laboratories of the New School of Mines were employed in umpire work. During this time many important local problems were solved. Against the results of careful chemical analyses of ores, assay-returns were often checked. In many cases the assay-methods of mine and custom-smelter were compared, and both often found faulty for the ore concerned. A wide range of ores was covered. Many of the chemical analyses and assays were made by Dr. F. C. Lincoln, Professor of Metallurgy, now of the Montana State School of Mines. A varied series of instructive assays was prepared by Prof. R. B. Brinsmade, now of the West Virginia State University. Single assays and given series of tests were undertaken by H. T. Goodjohn, now chief chemist to the Cia. Metalurgica de Torreon, Coahuila, Mexico; by H. J. Hubbard, now superintendent of the Butters Divisadero Mines, Jocoro, San Salvador, C. A.; by E. D. Morton, now superintendent of the Arizona & Nevada Copper Mining Co., at Lunning, Nev.; and by A. W. Edelen, now superintendent of the Angangueo Unit of the American Smelting & Refining Co., in Michoacan, Mexico. A critical comparison of assay-methods that were found to be followed in the case of certain gouge-ores mined in the Mimbres range in New Mexico, and about which there had been much controversy, was made by D. F. Riddell, then Acting Professor of Assaying, and now superintendent of the Providentia Mines Co. of Parral, in Chihuahua, Mexico. To him is due the credit of much that is contained in the following notes, which he has generously permitted to be used in advance of the publication of the complete results.

The Mimbres ore is representative of a large number of somewhat complex ores, high in silver, from the dry region of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Among other uncertainties connected with many of these ores, assay-determinations checked poorly; the values in precious metals, as returned by the smelters, were frequently too low, and on account of their variant character, even in the case of the same ore, the assay-results were very unsatisfactory.