Table of Contents

The great majority of minerals are compounds of two or more elements, though a few are native elements, i. e., elementary substances, as gold, silver, platinum, copper, carbon, and sulphur, which are found naturally. Minerals may be conveniently divided into the following eight Major Mineral Groups, and the descriptions will be in accordance with this plan:

- Native elements.

- Sulphides and arsenides.

- Oxides.

- Chlorides, fluorides, etc.

- Carbonates.

- Silicates.

- Phosphates, etc.

- Sulphates.

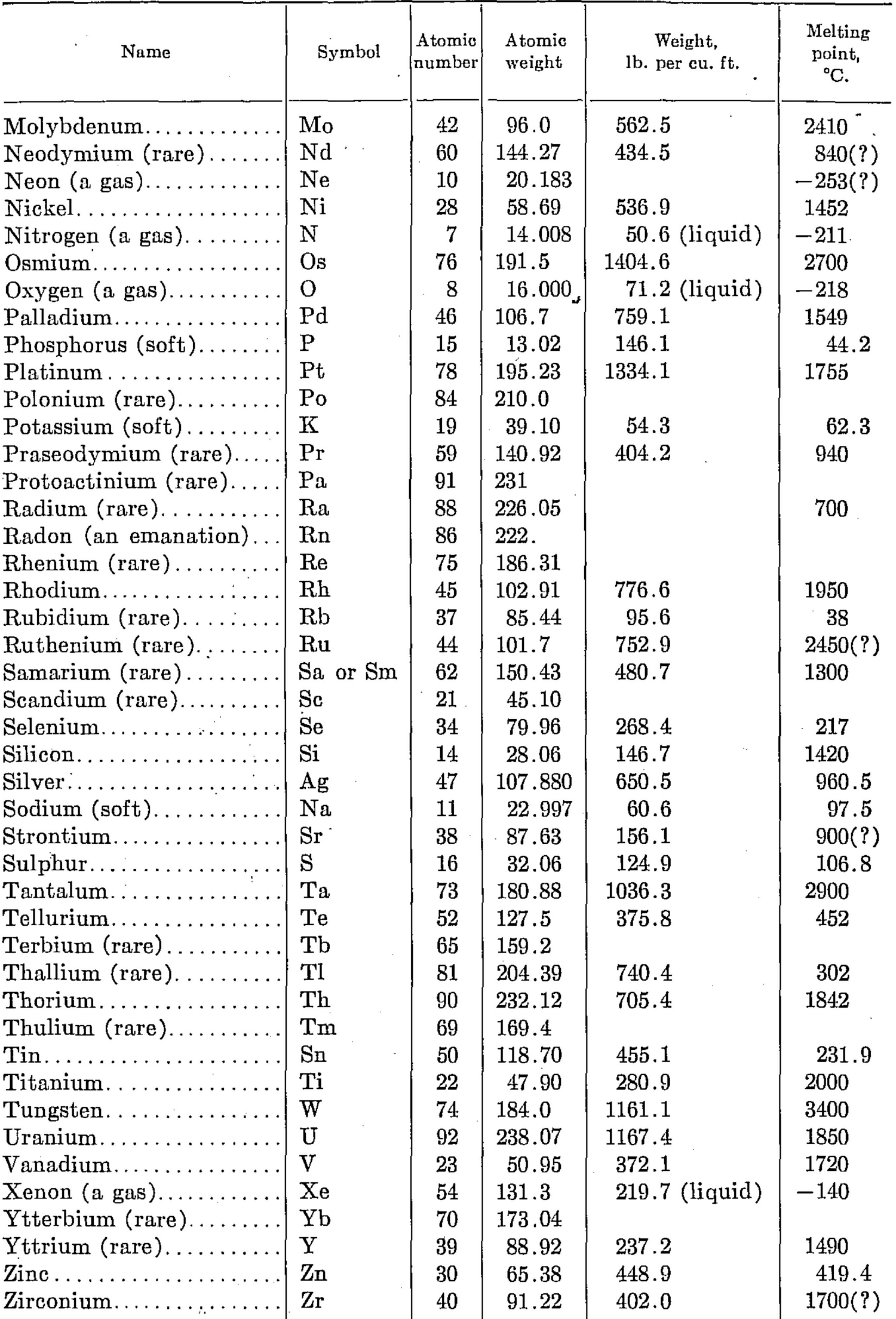

In the following descriptions of minerals, H is used for hardness, and G for specific gravity. After the name of an element is its symbol; and the names of mineral compounds are usually followed by their composition formulas.

How to Study the Mineral Descriptions

Study these descriptions with the specimens before you, and wherever possible, test the properties as described in the text in accordance with the following plan:

Take, for example, the specimen of galena. Turn to the description of galena. Note the appearance of the specimen, bright like a metal, thus corresponding to metallic luster, as given in the text. The specimen looks like lead; compare this with what the text states about its color. Using the point of a knife, dig a little powder from the specimen, and note the color of the powder when rubbed off on the palm of the hand or on a piece of white paper. The powder is gray; but if you happen to get it very fine, it will be darker gray than the specimen. See what the text states. While doing this, you have got the impression that the mineral is fairly soft. The text gives the hardness as H = 2.5 to 2.75; look at the Scale of Hardness, and see where these numbers fit into it. Heft (weigh) the specimen in the hand, and compare the impression it gives you with the specific gravity as given in the text. Remembering that the piece you are examining was broken from a larger piece, note how it has broken, with very smooth, flat, brilliant surfaces, indicating very perfect cleavage, which agrees with the text. The specimen may have been broken from a single crystal, in which case, the corners and edges of the whole piece are square, with occasional steps that are also built on the square. If the specimen is made up of a great many small crystals, each will also show the square corners, edges, and steps on the broken surface. Break out a very small bit, examine it carefully, and note that it is bounded by six faces (barring steps), all showing equally perfect cleavage. This shows that galena crystallizes in the cubic system, and that its cleavage is cubic. Read the entire description of galena as given in the text.

Quartz Specimen

Compare it with galena, and note that quartz does not have a metallic luster; its luster is like that of glass. Compare with the description of quartz. The specimen is white. Note what the text states about the color of quartz. Try to powder the quartz with the point of a knife; if this does not work, grind a corner of the specimen into a specimen of corundum and note the color of the powder. Read what is stated about the powder in the text. When trying to get some powder by digging with the knife, you get the impression that quartz is very hard. Try again, pressing very hard and pushing slowly; the black mark on the quartz is steel from the knife. See if you can scratch the knife blade with the quartz. The results show that quartz is harder than steel. Note what number is given in the text for the hardness of quartz, and then look up its place in the Scale of Hardness. Heft the specimen in the hand, and compare its weight with that of the galena specimen. The specific gravity of quartz, as given in the text, is 2.6 to 2.66; galena is nearly three times as heavy. Verify this by comparing the numbers (specific gravities). The specimen you are examining was probably broken of a larger piece; examine the surface and note that it is rough and irregular. Compare this with what the text states regarding the cleavage of quartz. Read the whole description of quartz as given in the text, but do not attempt to memorize all the information about the varieties.

It is important that the student have a great deal of practice in observing and testing the properties of known specimens, so as to train the eye, the hand, and the general powers of observation. This will be a fine preparation for the much harder task of identifying specimens whose names are not given. Work through the named specimens in your set, systematically observing and comparing the results obtained with the statements in the text.

After finishing with these, unnamed specimens may be identified by the use of the mineral table. It is not always possible to identify a mineral by its appearance or even by applying all the simple tests given in the table. Often the most accomplished mineralogist must use the appliances of a laboratory in testing a mineral, before he can identify it. But by using the table to identify a considerable number of “unknowns,” the student is getting experience that familiarizes him with the commoner minerals; and he gradually learns to recognize them at sight, or after testing the weight and hardness. But because the same mineral is found with such a variety of appearances, a great deal of practice is required before one becomes familiar with all varieties. Experienced mineralogists occasionally fail to recognize at first sight an unusual variety of some common mineral.