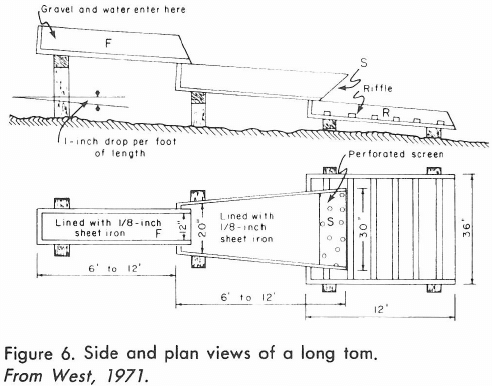

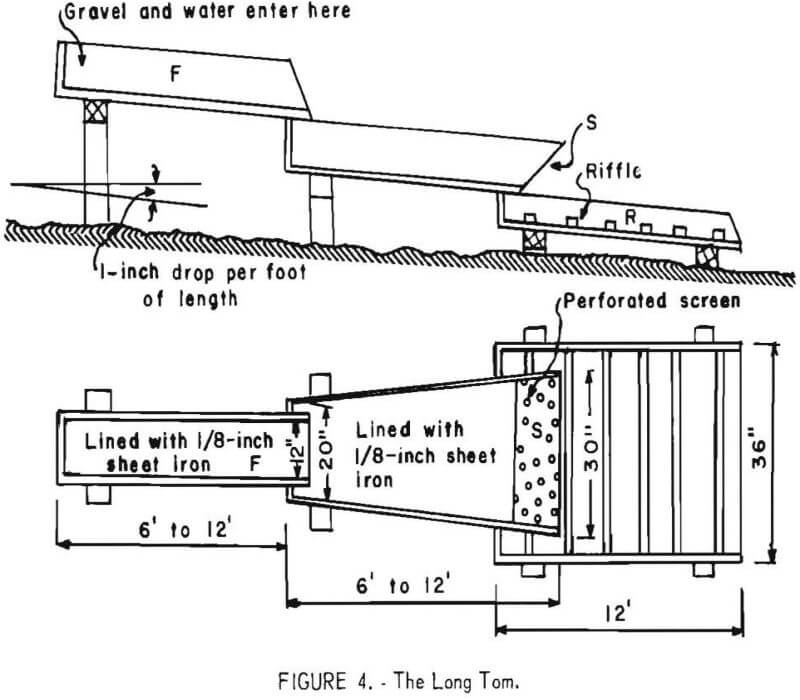

The Long Tom is a sluice variant and as you would expect the LONG TOM and the dip box are included here because of their simplicity and potential usefulness. The long tom is a small sluice that uses less water than a regular sluice. It consists of a sloping trough 12 feet long, 15 to 20 inches wide at the upper end, flaring to 24 to 30 inches at the lower end. The lower end of the box is set at a 45 degree angle and is covered with a perforated plate or screening with one-quarter- to three-quarter-inch openings. The slope varies from 1 to 1-2/2 inches per foot. Below this screen is a second box containing riffles; it is wider and usually shorter and set at a shallower slope than the first box (Figure 6).

The long tom uses much less water than a sluice but requires more labor. Material is fed into the upper box and then washed through with water (Photo 5). An operator breaks up the material, removes boulders, and works material through the screen. Coarse gold settles in the upper box and finer gold in the lower. The capacity of a long tom is 3 to 6 yards per day. Other than using less water, advantages and disadvantages are the same as for sluices.

Dip-box. The dip-box is a modification of the sluice that is used where water is scarce and the grade is too low for an ordinary sluice. It is simply a short sluice with a bottom of 1 by 12 inch lumber, with 6-inch-high sides and a 1 to 1-½ inch end piece. To catch gold, the bottom of the box is covered with burlap, canvas, carpet, Astro-Turf or other suitable material. Over this, beginning 1 foot below the back end of the box, is laid a strip of heavy wire screen of one-quarter-inch mesh. Burlap and the screen are held in place by cleats along the sides of the box.

The box is set with the feed end about waist high and the discharge end 6 to 12 inches lower. Material is fed, a small bucketful at a time, into the back of the box. Water is poured gently over it from a dipper, bucket, or hose until the water and gravel are washed out over the lower end. Gold will lodge mostly in the screen. Recovery is enhanced by the addition of riffles in the lower part of the box and by removal of large rocks before processing. Two people operating a dip box can process 3 to 5 cubic yards of material a day. As with a sluice, fine gold is not effectively recovered.

Summary. Sluices and related devices were commonly used in the early days of placer mining. Today, sluices are important in a large number of systems, ranging from small, one-person operations to large sand and gravel gold recovery plants and dredges. Recent innovations, such as the addition of long-strand Astro-Turf to riffles and the use of specially designed screens, have resulted in increased recovery of fine and coarse gold. Sluices are inexpensive to obtain, operate, and maintain. They are portable and easy to use, and they understandably play an important role in low-cost, placer-gold-recovery operations, especially in small deposits.

Vortex Drop Riffle Sluice

A long tom usually has a greater capacity than a rocker and does not require the labor of rocking. It consists essentially of a short receiving launder, an open washing box 6 to 12 feet long with the lower end a perforated plate or a screen set at an angle, and a short sluice with riffles (fig. 4). The component boxes are set on slopes ranging from 1 to 1½ inches per foot. The drop between boxes aids in breaking up lumps of clay and freeing the contained gold.

A good supply of running water is required to operate a long tom successfully. The water is introduced into the receiving box with the gravel, and

both pass into the washing box. The sand and water pass through the screen’s ½-inch openings and into the sluice. The oversize material is forked out. The gold is caught by the riffles. The riffle concentrates are removed and cleaned in a pan. Quicksilver may be used in the riffles if the gravel contains much fine gold.

The quantity of gravel that can be treated per day will vary with the nature of the gravel, the water supply, and the number of men employed to shovel stones into the tom and then fork them out. For example, two men, one shoveling into the tom and one working on it, might wash 6 cubic yards of ordinary gravel, or 3 to 4 cubic yards of cemented gravel, in 10 hours.

A tom may be operated by four men two shoveling in, one forking out stones, and one shoveling fine tailings away. Where running water and a grade are available, a simple sluice is generally as effective as the long tom and requires less labor.

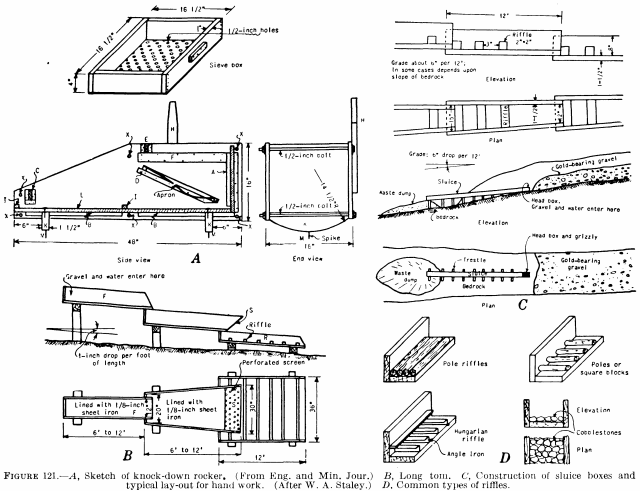

The long tom (figure 121, B) usually has a somewhat greater capacity than the rocker and does not require hand labor or power for rocking but requires a good supply of running water and often does not give as complete recovery of the gold. Wilson states that two men, one shoveling into the tom and one forking out the large stones and keeping it clear, can wash 6 cubic yards of ordinary

gravel or 3 to 4 yards of cemented gravel in 10 hours. Toms are used rarely now in the United States; where running water and grade are available a simple sluice is as effective and requires less labor.

In operation the gravel is shoveled into the tom (or flume immediately ahead of it), where the fine material is washed through the screen and the larger rocks are forked out and discarded. The gold and heavy sands are caught behind the riffles, and when these become filled up the concentrates are removed and cleaned in a gold pan. Mercury sometimes is added to the box to catch fine gold.

Surf washers are similar to long toms but usually are shorter and wider. They are set so that the incoming surf rushes up the sluices, washes material from the screen box or hopper, and, upon retreating, carries it over the riffles and plates. The duty per man averages about 3 to 5 cubic yards in 10 hours. One man can tend two surf washers, and in one recorded instance 8 cubic yards were handled in 10 hours.

Hand-shoveling into boxes or sluicing requires a plentiful water supply and a good bedrock gradient or slope to carry away the washed gravel. The method is adapted to rich gravel up to 6 or 8 feet in depth or to gravel that has already been partly concentrated by ground sluicing or booming. The gravel is loosened by picking and is shoveled by hand into the head of the sluice, which consists of a series of telescoping riffled boxes (fig. 121, C, which also shows a typical lay-out for hand work).

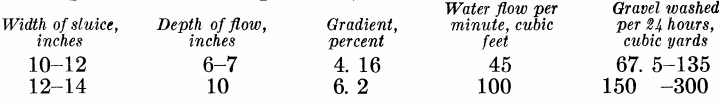

Riffles are constructed in various ways, four common types being shown in figure 121, D. The quantity of water available will control the scale of operations and the size of sluice to be used. A minimum flow of 15 to 20 miner’s inches (170 to 225 gallons per minute) is required for a 12-inch sluice set on a steep gradient. Boxes are 8 to 24 inches wide, and there may be from three to as many boxes as are required to carry the tailings to a suitable dumping ground. Concentrates from the sluices are panned or washed in a rocker to effect the final separation of the gold. The amount of water required for sluicing varies; about 1.3 to 3 cubic yards of gravel can be handled per 24 hours with a flow of 1 cubic foot of water per minute, equivalent to about 3,600 to 8,300 gallons of water per cubic yard. Young cites two examples of sluice capacities, as follows:

Under ideal conditions a good miner can shovel 15 cubic yards of gravel per shift into boxes elevated not more than 3 or 4 feet above bedrock. Wimmler states that 7 or 8 cubic yards per man-shift constitutes an average performance in Alaska.

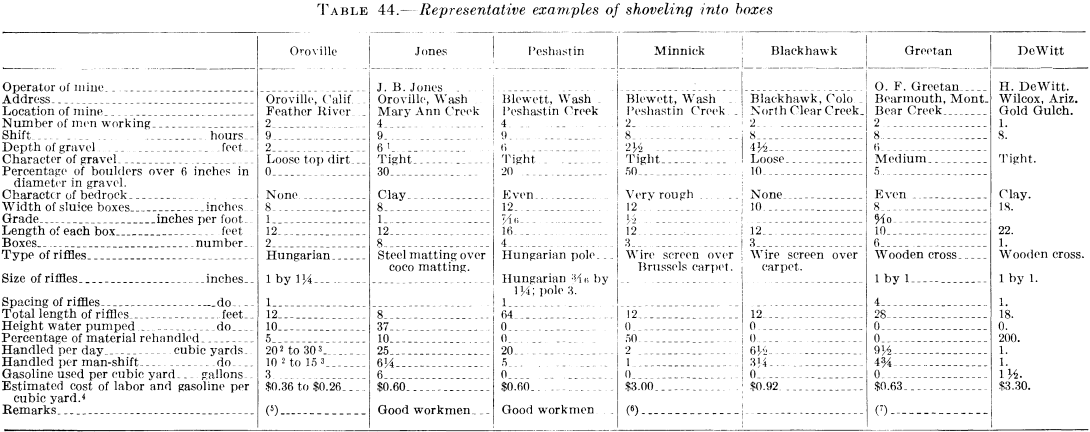

Table 44, reproduced from Information Circular 6786 by E. D. Gardner and C. H. Johnson, gives data on shoveling into boxes, which are typical of this method of working and show wide variations in working costs under different conditions.