Table of Contents

There are three great rock-making processes, namely:

- sedimentation

- movements of the melted rock or rock magma from within outwards

- metamorphism, or transformation of rocks by heat, pressure, and the influence of hot liquids and gases.

These will now be discussed in order; and after the description of each process, there follows an account of the principal kinds of rocks formed by that process. Reading below will explain all the various types of rocks and how they are formed.

Disposition of the Sediment

It is now proper to inquire into what becomes of the vast quantities of material being carried from the land into the ocean; this will throw some light on the effects of the same agencies that have been working on the earth for ages.

The bottom of the ocean is covered with sediment, coarser in the shoal water, and becoming finer with the increasing depths. The edge of these deposits can be seen, between high water and low- water levels, as gravel and sand; while finer material is found in the deeper waters. At the mouths of many rivers, the building up of extensive shoals, stretching far into the ocean, accounts for a large amount of the material lost from the land; and in the lowlands, in such countries as Holland, Belgium, and Guiana, more is accounted for.

Origin of Sedimentary Rocks

If conglomerate rock be compared with a bed of gravel, it is plain that the rock was at one time loose gravel;  it became rock by a natural process of cementing. A similar conclusion is arrived at by comparing sand stone with beds of sand lying in layers; shale and some kinds of limestone look rather like hardened mud. These resemblances are still more suggestive when the fossils (which are petrified bodies of plants and animals) in these rocks are found to be exact representations of the plants and animals buried in the sediments. There have been preserved even such details of the original sediments as ripple marks on sand, mud cracks caused by the drying of mud left bare at low tide, rain drop marks, etc,

it became rock by a natural process of cementing. A similar conclusion is arrived at by comparing sand stone with beds of sand lying in layers; shale and some kinds of limestone look rather like hardened mud. These resemblances are still more suggestive when the fossils (which are petrified bodies of plants and animals) in these rocks are found to be exact representations of the plants and animals buried in the sediments. There have been preserved even such details of the original sediments as ripple marks on sand, mud cracks caused by the drying of mud left bare at low tide, rain drop marks, etc,

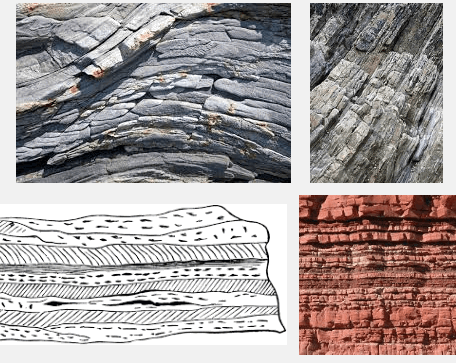

The sedimentary rocks are made, in one way or another, from the broken-down rocks of past ages. With the exception of some limestones and quartz sediments precipitated chemically, they are formed of fragments of older rocks, or of the shells, etc., of animals and plants. But a few sedimentary mineral deposits, particularly gypsum and rock salt, are exceptional. The layered structure, stratification, of sedimentary rocks is similar to that of the corresponding loose material.

The layers represent periods of deposition, between which the conditions changed. For example, between two layers of limestone, there is often a thin seam of shaly material, registering a time when clayey matter was worked off from the shore. A layer is called a stratum; but if very thin, it is called a lamina (plural, laminae or laminas). So the layers of sandstone and limestone are called strata, but the thin layers of shale are called laminas. The consolidation was due partly to cementing and partly to pressure.

Rock Classification

The sedimentary rocks are classified as follows:

- Conglomerate, breccia, arkose.

- Sandstone, graywacke.

- Shale.

- Limestone and other rocks formed from dissolved matter.

There are certain sedimentary rocks that are of more value than ordinary rocks; these are sought after and mined, and so have already been described in Part 1. These are: Coal, gypsum, salt, siderite, limonite, hematite, and phosphate.

How Conglomerate is Formed

The prospector may expect to find rocks corresponding to any collection of rock waste that is now to be seen on the surface of the earth. The beds of gravel of the past ages are now conglomerate, consisting of worn rock fragments of all sizes, boulders, cobbles, pebbles, sand and even silt. As there is often a grading of size, on the seashore, from coarse, at the higher levels, to fine, at the lower levels, so at times conglomerate is found that gradually passes from large to small pebbles and, finally, into sandstone. Occasionally a pebble or boulder in a conglomerate is a worn piece of an older conglomerate, showing that a part of the earth’s crust had been twice broken up, worn, and re-cemented to solid rock.

Occasionally a pebble or boulder in a conglomerate is a worn piece of an older conglomerate, showing that a part of the earth’s crust had been twice broken up, worn, and re-cemented to solid rock.

The pebbles in conglomerate may be pieces, from the size of a pea up, of any mineral or rock (including volcanic fragments) hard enough to have survived the amount of wear undergone by the rock waste before it was cemented. The spaces between the pebbles are filled with sand, silt, etc. The cement is commonly silica, calcite, or limonite.

Since the materials of conglomerate are pieces of various kinds of rocks, the specific gravity of conglomerate varies, but is not far from 2.75.

Volcanic agglomerate, volcanic tuff, and volcanic ash are rocks made by the consolidation of fragments of volcanic rock, the pieces being large in agglomerate, smaller in tuff, and fine as dust in volcanic ash rock.

Breccia

Breccia is a rock composed of angular pieces of rocks cemented together. It is often not sedimentary, as the broken material has been consolidated without transportation and wearing by water. Volcanic breccia is composed of pieces of lava of moderate size.

Sandstone

Sandstone is a stratified rock composed of grains of sand (mostly quartz), from the size of a pea down, more or less rounded, consolidated by pressure and a natural cement, which may be silica, calcite, oxide of iron, or clayey material. The grains are mostly quartz, sometimes large enough to be easily seen, forming a coarse sandstone; sometimes it is fine grained. On one side, sandstone shades into conglomerate, and on the other side, into shale.

The color of sandstone depends largely upon the cementing material. Silica or calcite makes a gray or white sandstone; oxides of iron give a red, brown, or yellowish color. The value of sandstone as a building stone depends upon its color, its texture whether fine or coarse, its strength and durability (depending on the cement), and its working qualities. Very complete cementing with silica gives a stone hard to work. On the other hand, some sandstones have been consolidated by pressure with very little cement; these are weak and not durable.

Sandstone very completely cemented with silica has a hardness near to that of quartz. Stones in which the grains are only slightly cemented, or in which there is a good deal of calcite or clay, are softer. G = 2.63 to 2.66.

Graywacke

Graywacke is made up of grains, more or less angular, of quartz, feldspar, and various other minerals and rocks. It is sometimes so fine-grained that the microscope is needed to see the structure. The cement is usually silica. Graywacke is commonly classed as metamorphic.

Arkose

Arkose is a sandstone derived from granite or gneiss, the waste of which was not moved far or water-worn very long, so that plenty of the feldspar remains.

Shale

Shale is mixed clay, mud, and silt consolidated by pressure and to a less extent by cementing. It forms in thin layers or laminas, which are easily separated, so that shale is usually a rock of little strength. It varies in composition, being sometimes mostly clay, in other cases, calcareous, (approaching limestone), siliceous or sandy (approaching sandstone), or ferruginous (with oxides of iron). Bituminous shale is charged with blackish material, often of the nature of petroleum; hence, it is called also oil shale, and is sometimes used for the production of oil, with ammonia as a by-product.

Fossils are abundant in shale, the soft material and quiet depths having preserved the forms of plants and animals. Shale has preserved its clayey nature and composition. It can be ground and used in making bricks, tiles, etc. It is easy to scratch with a knife. G = about 2.7.

Limestone

Limestone is rock formed of the shells of minute plants (algae, etc.) and animals (foraminifera, etc.), with fragments of the shells of larger animals, all set in a consolidated mud that is made, partly, of the ground-up shells of animals, and, partly, of carbonate of lime that has been precipitated by the escape from the water of the carbonic acid that held it in solution. Limestone is composed mostly of carbonate of lime, and that part of it which forms the shells of animals was extracted from the water in which the animals lived. Its original source was from the rocks weathered by the action of carbonic acid. Deposition of carbonate of lime mud is going on now, and it is found to be composed of the same materials (shells of foraminifera, etc.) as are found in limestone rocks. Chalk is made up largely of these shells and their fragments. Coral reefs and islands are built up by animals of a low order, which extract carbonate of lime from the sea water for this purpose; the building is aided by sea-weeds, which have the same power. Limestone is sometimes partly formed of coral, in fragments or in reefs.

Fossils are plentiful in limestone, particularly those of shell-fish, the shells of which sometimes form the greater part of the stone. The hardness of limestone is close to that of calcite (for which H=3) of which it mostly consists. Its specific gravity is from 2.7 to 2.9.