Table of Contents

Wet Metal Assay Techniques include a method by which the “ore” is turned into powder and thoroughly dissolve it in some liquid, usually an acid, or mixture of acids, and then to recognise the presence of some known metal or metals by the peculiarity of the precipitate produced, when a reagent has been added to the solution. If the mineral is likely to contain sulphur or arsenic or other such volatile substances in its composition (such as iron pyrites, copper pyrites, galena), a good plan is to powder and roast it in order to drive off the sulphur, and to leave the metallic portions in the form of oxide, and thus in a proper condition for easy examination. There are certain minerals, as graphite, cinnabar (the principal ore of mercury), some oxides, sulphates, chlorides, and a number of silicates, that are not soluble in acid. So as to simplify the testing of such as these, it is just as well to add to the powdered mineral about four times the weight of carbonate of soda, and to melt them in a crucible or other apparatus, so as to leave the metallic portion in a condition to be dissolved by hydrochloric acid; but let it be remembered that the above methods are only suggested to render the tests more accurate than they would otherwise be.

Notwithstanding that the blowpipe tests are those chiefly to be depended upon, the following wet ones may be of use in determining the presence of some of the metallic bases in many of the common ores met with ; and the apparatus required is not very large, consisting of three acids (hydrochloric, nitric, sulphuric), potash, ammonia, protochloride of tin (if convenient) for the gold test, copper, and zinc, a few test tubes, porcelain capsules, &c. The principal objection to the wet process is the inconvenience of carrying about powerful acids; at the same time, any chemist, if desired, will put them in strong and properly stopped bottles, which, when packed carefully in the compartments of a small box, will stand a good deal of knocking about.

The finely powdered mineral should be dissolved in hydrochloric acid or nitric acid (the latter being a substitute for roasting, and is the most suitable when the substance is a sulphide, or arsenide, or metallic alloy), and reagents added.

Place a little powdered ore in a test tube or other convenient apparatus (such as a porcelain dish), add a little water and pour in nitric acid; heat this over a spirit or other flame for a short time.

The clear solution is called the original solution, and (if there be any undissolved matter left as a residue at, the bottom of the tube) should be filtered or decanted into another test tube. To the clear solution add a little hydrochloric acid, when, if a precipítate is formed, it is,

Chloride of Lead, Chloride of Silver, or Mercurous Chloride

Pour all the liquid off, and then shake this precipitate with ammonia and observe the results:

If dissolved it is chloride of silver.

Confirmatory test for silver: add potash to the original solution and a brown precipitate would be produced.

If blackened it is mercurous chloride.

Confirmatory test for mercury: add potash to original solution and a black precipitate would be produced. Metallic copper (clean) placed in the solution would become silvery-looking.

If unchanged it is chloride of lead.

Confirmatory test for lead: add to original solution some sulphuric acid, and stir ; a white precipitate, sulphate of lead, would be formed at the bottom of the tube.

Suppose, however, that no precipitate was formed on the addition of hydrochloric acid to the original solution. The presence of some of the metallic bases is best determined by passing sulphuretted hydrogen gas through the acid solution. If a precipitate is formed it may, if black, show the presence of mercury, lead, bismuth, platinum, tin, gold, and copper; if yellow, of tin, antimony, arsenic, or cadmium ; but should no precipitate be formed, the addition of other reagents has to be made to determine the presence of iron, zinc, manganese, copper, nickel, and cobalt, &c.

The prospector will, however, find that usually his best plan is to take portions of the original solution, and to test them, one at a time, as follows :—

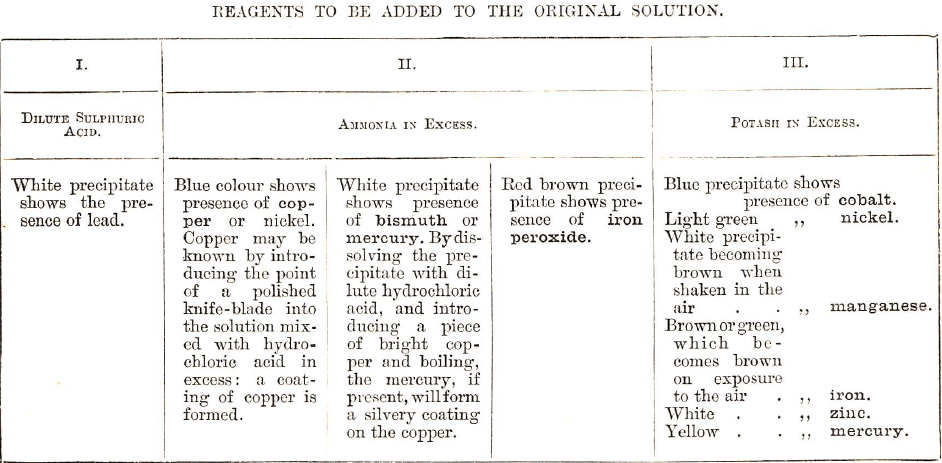

To separate portions of the original add reagents as in Table on the next page. The presence of antimony may be noted by adding a little hydrochloric acid to the original solution, and, introducing a piece of zinc—a sooty black precipitate will be the result.

To test a mineral for gold, the specimen must be thoroughly dissolved in aqua regia (4 parts hydrochloric and 1 nitric acid), then protochloride of tin added. The slightest trace of gold will cause the purple precipitate (called purple of cassius) to be formed; if a bright red solution results, there is platinum present. If, instead of the protochloride of tin, a solution of sulphate of iron (copperas) be added, the gold would be precipitated as a brown powder.

Though, generally, testing for a metal in a mineral is most satisfactorily performed by means of the blowpipe, there are cases in which there is great difficulty in obtaining proper results; for instance, when several metallic compounds are combined in the same specimen. Under such or other circumstances, individual tests, by means of the addition of reagents to the original solution, are most useful.

Again, the action of an acid on a mineral frequently enables the operator to determine whether the mineral is a silicate, a carbonate, &c.—if the former, sometimes by gelatinization; if the latter, by effervescence; and the evolution of nitrous acid vapours will suggest that copper, copper pyrites, or some metalliferous substance, not an oxide, may be present.

Wet Gold Assay

Powder about half an ounce of ore. Add four times its weight in a mixture of 4 parts hydrochloric and 1 part nitric acid, in an evaporating dish or other apparatus. Evaporate the decanted solution to dryness, hydrochloric acid being added as evaporation proceeds. Add sulphate if iron, dissolved in water, to the gold solution, both being previously warmed. The gold is precipitated as a brown powder. Filter the solution and weigh the dry precipitate. This method, however, is not to be recommended so much as the dry assay.

Wet Silver Assay

Dissolve the powdered ore in nitric acid, and throw down the chloride of silver precipitate by adding a solution of common salt or else hydrochloric acid. If chloride of lead and mercurous chloride are absent, the solution may be decanted or filtered, and the chloride of silver weighed : three-quarters of the weight very nearly represents pure silver. Or else the chloride of silver may be fused and the metallic silver collected and weighed.

Wet Lead Assay

Place the powdered ore in a porcelain dish or other convenient and suitable apparatus, and thoroughly dissolve it in strong nitric acid by heat until the residue is nearly white and red fumes cease to be given off. Add a few drops of sulphuric acid and evaporate to dryness ; then add water, and filter. As silica and certain sulphates may be in the residue, boil it along with carbonate of soda for about forty minutes. Filter. Dissolve the residue—carbonate of lead.—in acetic acid.. Add a little sulphuric acid to the solution. Filter or decant the solution. The residue- sulphate of lead—nearly represents 68 per cent, of metallic load.

Wet Copper Assay

The most accurate method of determining the amount of copper in an ore is to thoroughly dissolve the ore in acid, then to add ammonia until a blue colour is obtained and then to drop from a graduated burette a standard solution of cyanide of potassium until the solution has the colour taken out of it.

Number of markings on burette : present reading : known strength of solution : where x is the number of grains of copper in the weighed portion of the ore.

X/weight of ore x 100 = percentage of copper in the ore,

The burette method, like the dry assay, requires great care in order to insure accuracy, and might mislead one who has not studied and practised it, as certain metals other than copper may sadly affect the results. On this account there is no occasion for explaining the process in detail, as the prospector will find the following method comparatively simple.

Take finely powdered ore, say 25 grains, drive off sulphur, by roasting (q.v.) in a porcelain dish.

Dissolve by heating in nitric acid. Add a little sulphuric acid and evaporate to dryness. Dilute in water and pour the solution into a basin. If well polished sheet or other iron be placed in it, and left for an hour or so, the metallic copper will form on its surface, and by means of a feather may be rubbed off and weighed.

Or else (to avoid roasting). Moisten the powdered ore in sulphuric acid, and add nitric acid. Let it be thus heated for about an hour or so, and let nitric acid be constantly added during the operation. Add hydrochloric acid to get rid of nitric acid, which may be judged by absence of chlorine smells. Dilute with water and obtain copper on the inserted iron as before. To see that all the copper has been properly deposited, dip the polished point of a knifer blade into the solution; if it has not, a film of copper will be left on the knife.

Weight of copper/Weight of ore sample x 100 = percentage of copper in the ore.

Wet Iron Assay

To assay an iron ore by the wet method, the standard solution of bichromate of potash is, by means of a graduated burette, added to the iron solution (the powdered ore dissolved in hydrochloric acid); but like the other burette assays, this requires so much practice in order to secure reliable results, that there is no occasion to enter into details concerning it. The prospector will rarely require to know the exact amount of iron in an ore, and his own sense will perhaps guide him nearly as well as an assay, as great quantity and good quality are both necessary to make an iron ore payable.

Roasting

In roasting the powdered ore much care is necessary in order that the sulphur, may be expelled. The powdered ore placed in an open and shallow vessel, if possible, should be exposed to a low heat at first, and after a time the temperature may be raised. During the operation free access of air is requisite, and the ore must be constantly stirred by means of an iron wire bent at one end, or other suitable apparatus, so as to prevent clotting. When fumes cease to be given off the operation is finished, about a quarter of an hour being the usual time necessary.

Mechanical Assay of Ores

This is performed by crushing the ore and subjecting it to the action of water. If the powdered ore be subjected to the action of water running on an inclined plane or trough with a slope, the heavier particles of metals may be caught up in their descent by means of thin boards (riffles) fastened across the trough. Rough hides, with the hair upwards, may be used to intercept the heavier portions.